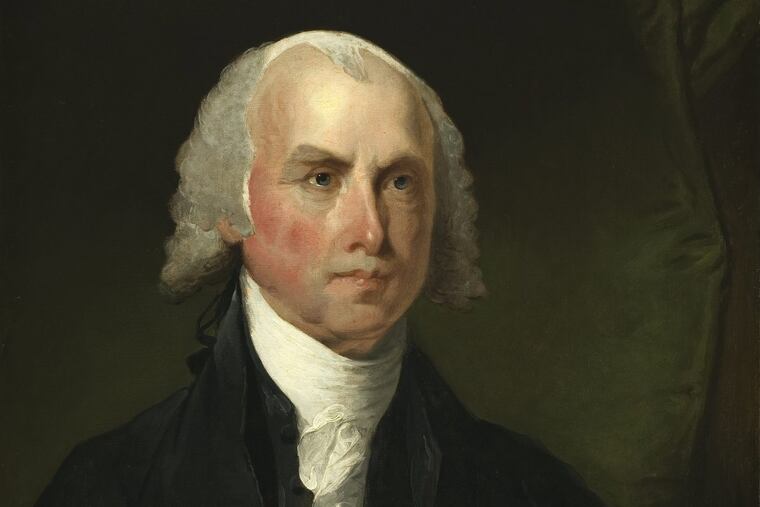

Medical mystery: James Madison's sudden collapse

The Founding Father's leadership and diplomacy skills would become legendary. Physically, though, he had challenges.

James Madison was a founding father of the United States, a great statesman considered the "Father of the Constitution" who became our fourth president in 1809.

But if physical strength were essential to being a leader of the young nation, history might have been rather different.

Madison, who stood at about 5-foot-4, never weighed more than 100 pounds. Physicians declared him too frail for military service.

His parents were so concerned for their son's health that they declined to send him to the College of William and Mary in nearby Williamsburg, Va., fearing the swampy climate, a breeding ground for malaria. Instead, he went to the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), where he finished his bachelor's degree in 1771 after just two years of study, and then stayed on to study Hebrew and political philosophy. Princeton touts him as its "first graduate student."

Back home in Virginia, Madison joined a patriotic pro-revolution group that oversaw the local militia. He was commissioned as a colonel of the Orange County militia, serving as his father's second in command, but did not see battle.

Madison began his political career as a member of the Virginia House of Delegates and then the Continental Congress in Philadelphia.

In 1775, he attended a militia drill, but suddenly collapsed without warning. Similar episodes – marked by loss of function and subsequent collapse, or the appearance of day-dreaming, or even agitation – plagued Madison throughout his life.

What caused these episodes? Were they neurological or psychological? How did they affect his presidency?

Solution

Madison's collapse at age 24 while on a military drill has been referred to as an "absence seizure" because the victim appears to momentarily be elsewhere. These seizures, a form of epilepsy also known as "petit mal" (from the French for "little illness") usually are brief, often less than 15 seconds and barely noticeable, in contrast to other seizure disorders.

Absence seizures begin in both sides of the brain at the same time, without warning. They are so brief that they sometimes are mistaken for daydreaming and may not be detected for months.

Signs may include staring off into space, smacking the lips together, fluttering eyelids, suddenly stopping speech, and sudden motionless without being aware of surroundings, even when touched. According to the Epilepsy Foundation, about 65 percent of children with these seizures outgrow them in their teens. Medications can usually help to control them.

But, of course, those weren't available to our fourth president, who was afflicted by these abrupt spells the remainder of his life. However, they didn't affect his longevity, as he lived to a remarkable 85 years old.

Nor did they seem to diminish the abilities of a man considered by some to be the most important political thinker in American history. He promoted freedom of religion, speech and the press, the rights of minorities under majority rule, the role of states' rights in the federal system, and the separation of powers. As secretary of state to President Thomas Jefferson, he oversaw the Louisiana Purchase, which doubled the nation's size. He served two terms himself, during a period that included the War of 1812. Historians rate him as an above-average president.

In retirement, Madison showed signs of agitation, though whether that had to do with his seizure disorder or anxiety over financial and personal troubles is not known. Worried about his legacy, he modified documents, removing some passages, and at times suffered physical collapse.

Allan B. Schwartz, M.D., is a professor of medicine in the Division of Nephrology & Hypertension at Drexel University College of Medicine.