Panic disorder treatment could be breath of fresh air

Take a deep breath. How often do you hear someone give that advice for calming down? Maybe you give it to yourself.

Take a deep breath.

How often do you hear someone give that advice for calming down? Maybe you give it to yourself.

You may be surprised to learn that a new biofeedback treatment for panic disorder suggests just the opposite.

The at-home treatment, which uses a machine called Freespira that measures respiration rate and carbon-dioxide levels in exhaled breath, trains patients to breathe slowly and shallowly, with an emphasis on more complete exhalation than many of us are used to. A small early study found that 68 percent of patients were panic-free a year after training with the device for a month.

"What we've learned from Freespira is that, if you have a panic attack, the last thing in the world you want to do is deep breathing," said Carl Robbins, a psychotherapist at the Anxiety and Stress Disorders Institute of Maryland who has used the device with 50 patients.

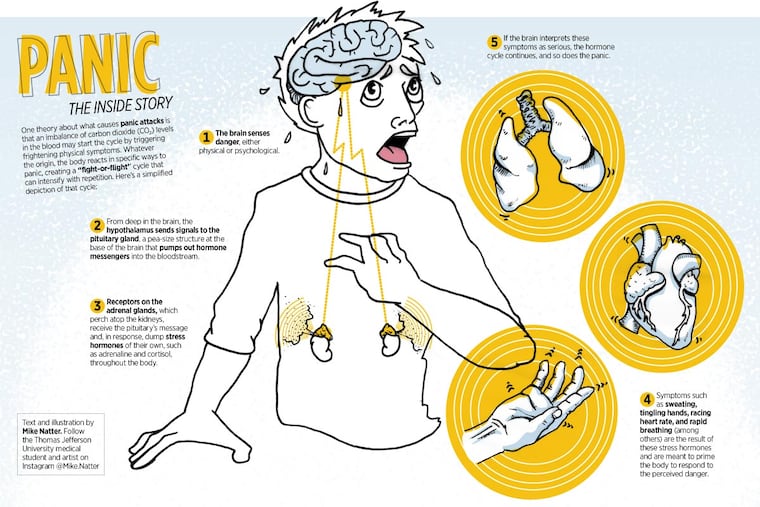

The theory behind the treatment is that improper breathing - too fast or too deep - triggers physical symptoms that spiral into full-blown panic attacks when anxious people worry that they're having a heart attack or some other catastrophic problem. The fear causes even more hyperventilation, leading to a vicious loop of physical symptoms and anxiety.

"Wow," Alan J. Russell thought when he heard all this. "Is that a big deal?"

Russell, a biological chemist who is chief innovation officer and executive vice president of Allegheny Health Network, was in a position to go beyond the small studies that led the FDA to clear the device for use in 2013.

He runs VITAL, an unusual program at Highmark Health, the big Western Pennsylvania health provider and insurer. The program gathers information on treatments that are "not yet ready for prime time in terms of classic reimbursement," he said. Freespira is among the first three treatments the insurer is testing to decide whether they merit insurance coverage.

VITAL (Verification of Innovation by Testing, Analysis, and Learning) is paying for 100 of Highmark's 35 million subscribers to try Freespira for panic symptoms. The program will then analyze whether the treatment works and reduces treatment costs.

Currently, no other insurance companies are covering Freespira's $500-a-month price tag, a barrier to widespread use.

In this area, only Marvin Berman, a neurofeedback therapist who runs Quietmind Foundation in Plymouth Meeting, offers the device to patients. He said a handful had used it, with lasting results. "Your brain is always looking for the more efficient way to do things," he said. "The whole dynamic becomes self-reinforcing."

Six million people in the United States have panic disorder, and 27 million have episodes of panic. Seemingly out of the blue, sufferers may experience sudden attacks of fear or feeling out of control. Physical symptoms include a racing or pounding heart, chest pain, sweating, breathing problems, tingling hands, and chills. Such symptoms prompt repeated emergency-room and primary-care visits.

People with panic disorder can become so afraid of the attacks they stop doing things they think are triggers. In extreme cases, they stop leaving their homes.

"It really starts to shrink the world in which people can operate," said David Yusko, a University of Pennsylvania psychologist who does not use Freespira. "Their lives get reduced to safe zones."

Patients typically are treated with cognitive behavioral therapy, a type of talk therapy that focuses on changing dysfunctional thoughts, as well as with antianxiety drugs and antidepressants. Learning to take slower breaths has long been part of panic disorder treatment.

Yusko, associate director of the Center for the Treatment and Study of Anxiety, adds exposure therapy, which helps people deal with their fears by facing them repeatedly. Finding skilled exposure practitioners is difficult, he said, but the combination of treatments is "supereffective."

He is skeptical that Freespira can "outperform" exposure therapy.

Many people with panic disorder chronically hyperventilate, or breathe too much. This can happen when they breathe deeply or too rapidly, and it leads to an imbalance of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the blood. When carbon dioxide falls too low, as it does when people hyperventilate, it creates the symptoms that can send vulnerable people into a panic.

The idea behind Freespira is to break the loop by retraining people to breathe properly, a skill that most of us lose after infancy, probably because we imitated our parents, Berman said. First off, breathe through your nose, not your mouth. Pull the breath into your stomach, not just the chest, and let your belly expand. Exhale fully.

Greg Tomita, vice president of marketing for Palo Alto Health Sciences Inc., which markets Freespira, said 70 percent of patients with panic disorder in trials had low CO2 levels at baseline. Though the other 30 percent had normal levels, their breathing was erratic. Both were helped by breathing training.

Freespira's FDA clearance was based on work by Alicia Meuret, a psychologist at Southern Methodist University. She declined to discuss the company or her research for this article.

David Tolin, a psychologist at the Institute of Living in Hartford, is now analyzing data from a multicenter trial that included 69 patients, 48 of whom completed treatment. Two months after treatment, 69 percent of those who stayed in the study had a significant reduction in severity of panic disorder symptoms. The attacks had stopped for 51 percent.

Tolin said that was similar to results for cognitive behavioral therapy but that Freespira was "much less time-consuming than most of the behavioral therapies that we would use."

Freespira measures respiration rate and CO2 through nasal tubes. Patients, who are instructed to practice for 17 minutes twice a day, see how they're doing on a computer tablet. Sound cues tell them when to inhale and exhale. Over four weeks, their breathing rate declines to six breaths per minute.

Getting it right while breathing evenly is not easy. Users are instructed to sip air as though it were a precious commodity.

"It is challenging," said Tomita. "It is not a relaxation exercise."

Colleen Kistner of Fallston, Md., who has suffered from frequent panic attacks for 20 years, participated a year ago in a test of Freespira.

This is how she described her attacks: "I literally feel like I've lost my breath. My chest is unbelievably tight. My hands go numb and tingly. I get very cold . . . and I feel completely disoriented and out of control."

She has tried cognitive behavioral therapy, exposure, and medication. Kistner, 39, found using the machine was hard at first. The breathing felt weird and even made her a little panicky, but she persevered. Soon, she started sleeping better. She felt more focused. When she'd feel nervous, the machine's breathing tone popped into her head like an annoying song hook.

"I think it calmed all of my system," she said.

She liked it so much that she begged to keep the machine. She used it twice when symptoms returned. She says she is panic-free now. "I feel like I have my life back."

A big question is why this would work. Is it the C02, or are patients benefiting from slower respiration, a period of meditative stillness, or the sense of control they get from seeing how their breathing changes?

"We have a pretty good sense that breathing retraining works," Tolin said, "but we have a million questions about why it works."

Paul Lehrer, a respiration expert at Rutgers University, said that hyperventilation alone would create a host of disturbing symptoms that could trigger emotional reactions, but that the pace and regularity of breathing were also important. No one breathes in perfect rhythm all day. We hold our breath when we're concentrating. We take in more air when we exercise. Irregular breathing in the form of frequent sighing and yawning, though, brings in more air and can contribute to hyperventilation. Breath-holding, and the subsequent compensation, also can lead to hyperventilation.

Breathing at five-and-a-half to six beats per minute is typically the "resonance frequency," where breathing efficiency is maximized. When Lehrer studied Zen monks in Japan, he found that was their breathing rate.

Breathing at this frequency stimulates and strengthens reflexes that help control blood pressure, pain, anxiety, and depression, and improves physical functioning, Lehrer said.

An obvious question is whether the machine might be helpful for other anxious people. One study found that low C02 levels were common in those whose anxiety manifested itself in other ways.

Tolin is now collecting respiratory data from everybody who comes to his clinic and is preparing for a controlled trial of people with anxiety.

VITAL's Russell is interested in that, too. "We're very excited to think about other uses for the device," he said. For now, though, their study is "focused like a laser" on panic.

Tolin said most of us need not worry about whether we're breathing just right. His own CO2 is on the low end. "A lot of us breathe wrong," he said, "but I think, for most of us, it's not a big deal. The body is pretty robust."

215-854-4944@StaceyABurling