Inside The OR: Ankle Replacement

Ankle replacements — complicated and uncommon — get patients on the go again.

As a mason, Thomas Walsh swung from scaffolds, climbed ladders, hauled around bricks and mortar. In his free time, the Downingtown resident played in two South Philly softball leagues and led the Gallagher New Year's Mummers brigade as captain, marching proudly down Broad Street for miles.

He did all this for 22 years, and all on a badly damaged ankle.

In the last two years, the pain became so strong that Walsh could barely stand for more than two hours at a time. Severe arthritis in his right ankle put the 61-year-old on disability last August.

"A typical day's worth of work now takes me four days to finish," Walsh said. "You make no profits that way."

He'd heard about people getting their creaky hips and knees replaced, but thought he'd just have to live with the pain.

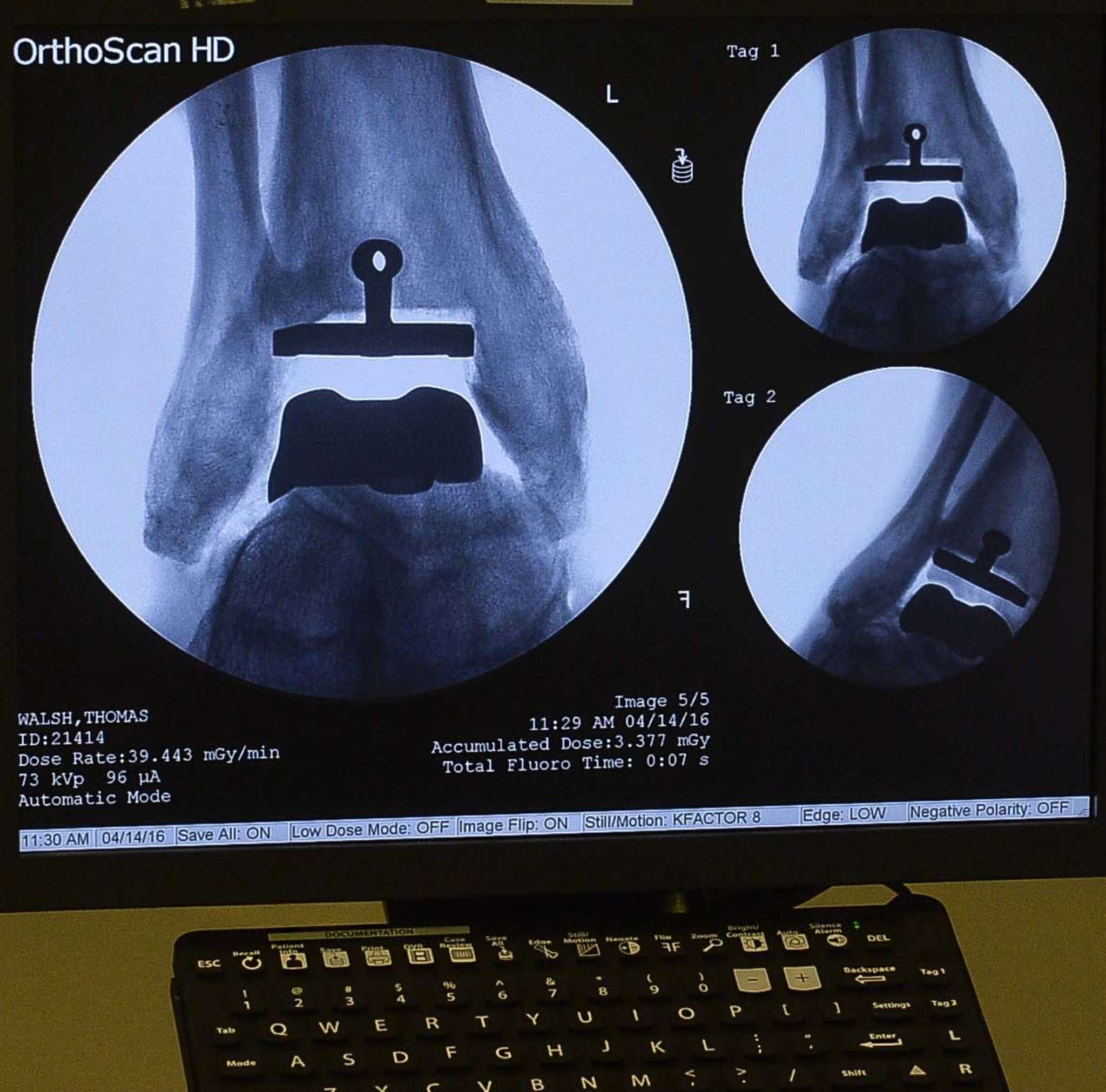

Last month, Walsh underwent a total ankle replacement at Rothman Orthopaedic Specialty Hospital in Bensalem.

His surgeon, Steven Raikin, director of foot and ankle services at Rothman, said the lower extremities are easy to ignore, "until they start bothering you."

"And when they start bothering you," he added, "it affects every aspect of your life."

Down on a patch of ice

One evening in January 1994, Walsh was walking home from a job site when he hit a patch of black ice and slipped. His 6-foot-4-inch frame splayed out on the sidewalk, his foot twisted in an entirely new direction.

He went to the emergency room. Surgeons set his ankle with plates and screws, and told him he would spend the next six months in a cast.

"When they finally took the cast off," he said, "my ankle had very limited mobility."

Over time, the battered cartilage in his ankle deteriorated. Anti-inflammatory medications dulled the chronic pain for a time, but eventually lost effectiveness.

"When there's bad arthritis, the body protects itself by trying to fuse the bones together to lock the ankle," Raikin said. "But the bones can never fully fuse so bone spurs are created and they are what cause the majority of the patient's pain."

After a few years of this, Walsh's ankle would swell within minutes of his sitting down. By the time he saw Raikin, he could no longer stand without a cane.

"I've been pushing through the pain to make sure that I got my kids into college," Walsh said. "I had to keep working to make sure that they had the quality of life that I would like for them." Caitlin, 23, is now an assistant field hockey coach at Davidson College, and Colleen, 20, will start her junior year at the University of the Sciences in the fall.

"Now I can take care of myself," he added, "and start replacing my parts."

A last resort

The ankle brings together three main components: the shin bone (tibia), a thin bone that runs alongside of it (fibula), and the foot bone (talus), which is at the bottom of the joint. But that's just the beginning of this complicated body part, which sits atop 28 bones linked by 30 joints.

A traumatic episode, such as Walsh's slip on ice, is the cause of 85 percent of ankle arthritis.

For years, the only option was a fusion procedure, in which screws and pins permanently meld the bones together. When it's successful, pain dissipates, but so does the joint's mobility.

Technological advancements in the last 15 years have allowed foot and ankle specialists to use artificial implants, which offer patients an increased range of motion without pain.

A replacement, such as those done in hips and knees, is much more complex in the ankle, due to its many moving parts.

"The wrist has similar difficulty," Raikin said, "but you walk on your ankle."

Roughly 6,000 ankle replacements are performed a year in the United States, a fraction of the 700,000 knee and 300,000 hip replacements that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recorded last year. Raikin replaces 40 to 50 ankles a year.

While growing in popularity, ankle replacements are still considered a last resort, as the implants don't last as long as those used in the hip or knee.

"You should wait as long as possible," Raikin said. Wait too long, however, and bone loss could mean the replacement parts can't be installed.

The Surgery

Raikin shaped the healthy remaining bone to fit the two new metal implants, and "press fitted" them onto Walsh's bone. This process - as the name suggests, the surgeon butts bone and implant together -helps bone to grow onto the implant's porous, sandpaper-like surface.

With the incision still open, Raikin moved the foot back and forth to test the range of motion. Seeing that it had roughly quadrupled, he made another adjustment to Walsh's tight Achilles tendon so he will get the most movement possible out of his new ankle - provided he dedicates himself to rehab.

Outfitted with a boot

Just hours after the surgery, Walsh saw a physical therapist to ensure that he could safely carry his weight on crutches while outfitted with a boot for the next six weeks.

Keeping weight off the foot for a while is crucial to the healing process as circulation at the ankle isn't as strong as it is in other joints, the surgeon explained.

By three months, patients can return to regular shoes, but it takes roughly a year before the ankle feels normal again.

For patients, the hardest part of recovery is managing their expectations.

"This is not a normal joint, and you have to work really hard with physical therapy to get range of motion back," Raikin said. "We can't replace the soft tissue around that area, and if it's been stiff from arthritis for a long time, patients aren't going to get as much motion as they may hope for."

Most patients - 85 percent - report that the new joint is still serving them well 12 years after surgery. Raikin has one patient whose replacement is 16 years out and still functioning. But as with hips and knees, people who get an ankle replacement in their 60s likely will live long enough to need another one.

And as with so many other aspects of health care, prevention in the form of weight management and regular, low-impact exercise will maximize a new joint's useful life.

Four weeks after surgery, Walsh - freshly outfitted with a boot - said he is dreaming about his first steps on a golf course and playing the sport he hasn't been able to enjoy since 1994.

koshea@philly.com

215-854-2237

@kelloshea