'I'm trying to change hearts and minds'

HER CLASSROOM MORE resembles a living room - with its green curtains and electric torch lamps . But Victoria Monacelli yesterday nevertheless laid down the law like the seventh-grade English teacher that she is.

HER CLASSROOM MORE resembles a living room - with its green curtains and electric torch lamps .

But Victoria Monacelli yesterday nevertheless laid down the law like the seventh-grade English teacher that she is.

"You have a responsibility to push yourself and keep trying - and ask questions if you don't understand something. I'm here at lunch every day. I'm here after school," she told her students on the first day of classes at Warren Harding Middle School, in the city's Frankford section.

"I don't know what you did last year. I don't know anything about you," she continued. "This is what I expect, and what I want you to do."

Harding Principal Terry Pearsall-Hargett listened approvingly off to one side. Entering her fourth year as Harding's principal, Pearsall-Hargett is well aware of the importance of teachers and students working together to boost achievement.

But she's also aware that despite take-charge teachers like Monacelli - who created the school's Web site - Harding for five straight years has failed to make adequate yearly progress, as defined by the federal No Child Left Behind Act.

"One day we might be outperforming No Child Left Behind, but it's a process. I think it takes a long time to turn a big ship around, and this is a big ship that has a lot of poverty," said Pearsall-Hargett, who spent 22 years in the Army Reserves, including a stint in the Middle East during Operation Desert Storm in 1991.

"When I was in Saudi Arabia, that's when I decided I wanted to be a principal - because I was a leader in the military," she added. "I'm trying to change hearts and minds. I'm trying to give kids an opportunity to learn in the way they learn, not in the way we learn."

At Harding, a racially diverse school of 1,143 sixth-through-eighth-graders, most students come from low-income families, the principal said.

She estimated that 25 percent receive special-education services while about 60 youngsters speak English as a second language. Their school was built in 1923 - the year its namesake died.

Still, Harding is not unique in failing to achieve the mandates of the federal law - largely based on annual reading and math exams.

Just 107 schools out of 268 in the district reached their goals for progress last year.

Thus, the majority of district principals and teachers began the new year yesterday working on the same puzzle: how to get student achievement up to federal standards in a district that is steadily cutting its budget to address a deficit.

"We're under the same budget constraints as everyone else, but we're optimistic at the beginning of the year. Teachers think they can spin straw into gold," said Lisa Haver, a Harding math and social studies teacher.

The school district this fall is implementing a series of strategies to help schools that have repeatedly failed to reach progress goals, said Cassandra Jones, interim chief academic officer.

The strategies include having teachers place greater emphasis on students reading more across all subjects, teams of administrators being sent to schools to help them improve weak areas based on test data from each school and incorporating more sports and other activities into after-school tutoring programs to get students more engaged in the learning process, Jones said.

At Harding, Pearsall-Hargett has hired a climate manager to coordinate the safety team, which includes school police officers, non-teaching assistants and employees from community-based organizations.

And she's launched a student court to teach students about the judicial system while giving them the opportunity to serve on juries to judge one another.

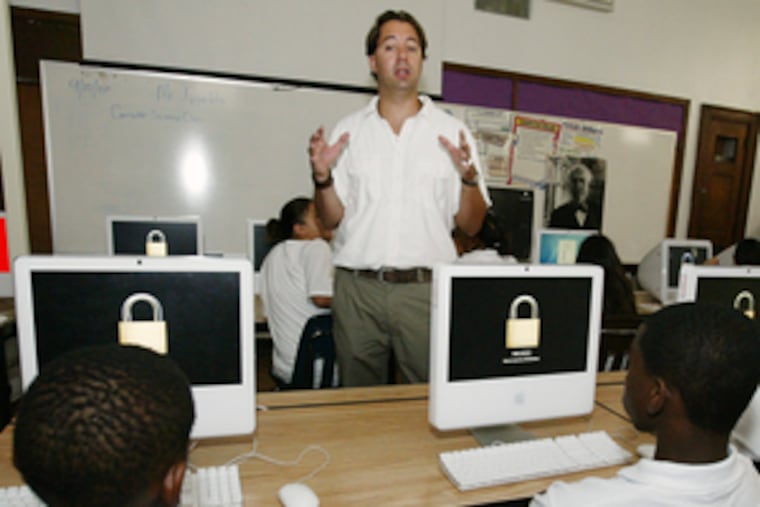

Harding has a library staffed by a certified librarian. It also has four desktop computer labs and six mobile labs.

A handful of Harding students gave their school passing grades - but with room for improvement - during lunch break, which featured sausage pizza and french fries and chicken nuggets and biscuits.

None of the students had heard of the No Child Left Behind Act nor its catchphrase, adequate yearly progress.

"I'm looking forward to learning new things, making lots of friends and doing what I have to do to go to high school and to make something out of me," said Jasmarie, 14, an eighth-grader.

Asked what she would change about her school, Jasmarie said: "People who swear they all that and they just violent and start fights after school."

Day-one happenings

Across the school district, attendance was 92.1 percent, up 1.12 percent from the first day last year, school officials said.

There were 38 teacher vacancies, down from 51 last year and 112 vacancies in 2005, they said.

Seven serious incidents - all student-on-student assaults - were reported, said James Golden, head of the district's safety office. An incident at South Philadelphia High involved at least six students, he said. *