Avalanche of Anguish

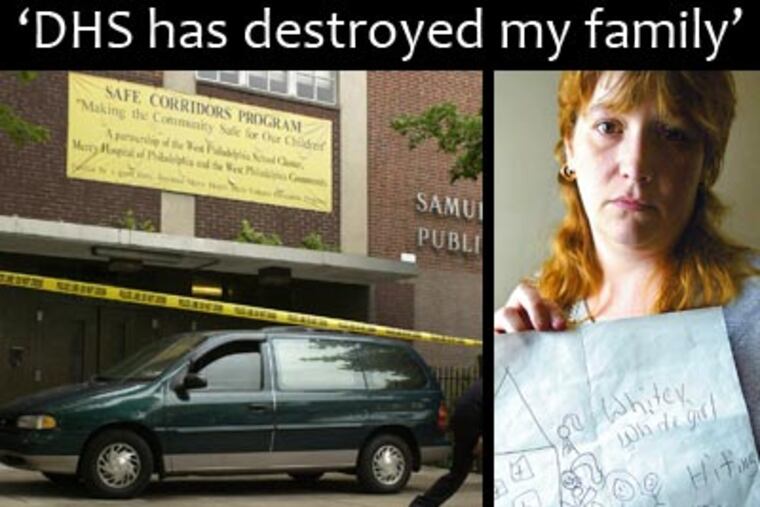

SHANNON BERTHIAUME knows she did something stupid, something she can't take back. In a fit of frustration, the mother of three drove her minivan into a West Philadelphia elementary school in 2005 to protest the escalating racial bullying her kids had suffered there. But her legal troubles were trivial compared to the avalanche of anguish that followed.

SHANNON BERTHIAUME knows she did something stupid, something she can't take back.

In a fit of frustration, the mother of three drove her minivan into a West Philadelphia elementary school in 2005 to protest the escalating racial bullying her kids had suffered there.

Although no one was seriously injured and the only damage was a scratch on the school door, Berthiaume was arrested and sentenced to a year of probation.

But her legal troubles were trivial compared to the avalanche of anguish that followed.

Social workers from the city's Department of Human Services took her kids away and kept them, pingponging between foster homes, for a year and a half.

When Berthiaume got them back, all three had been sexually molested in their foster homes, she said.

"My oldest son [then 14] came home bleeding from his rectum - a lot, like a woman bleeds [menstrually]," Berthiaume said.

That son, now 16, is in a group home for sex offenders, after DHS took him again when he molested his little brother. Her other two kids resent her for catapulting them into the misery that has marred their lives since their mother's arrest.

"DHS has destroyed my family," said Berthiaume, 37, wiping tears from her cheeks.

While judges and social workers often assume removing children from troubled homes will make them safer, the ordeal of Berthiaume and her family illustrates a disturbing epidemic in foster care:

Kids in foster homes are up to four times as likely to suffer sex abuse as other kids.

The odds worsen for kids unlucky enough to get placed in group homes and other institutional settings:

They're 28 times as likely to be sexually abused there, studies show.

And while predatory foster parents make the headlines, the abuse typically is child-on-child, experts agree.

As shocking as the statistics are, child advocates say sexual abuse occurs far more than even the most perverted mind can imagine.

"I've been doing this work for a long time and represented thousands and thousands of foster children, both in class-action lawsuits and individually, and I have almost never seen a child, boy or girl, who has been in foster care for any length of time who has not been sexually abused in some way, whether it is child-on-child or not," said Marcia Robinson Lowry, executive director of Children's Rights, a New York-based nonprofit.

"It is quite common."

A parental protest

When fire forced Berthiaume and her brood out of their charred Kensington home in November 2004, they relocated to West Philly, where she enrolled them in the Samuel B. Huey Elementary School.

They were the only white kids in the school.

That didn't matter to Berthiaume, who married a black man and whose youngest son's father is Puerto Rican.

But it apparently did matter to some of their classmates, who rarely let an opportunity pass to call them racial names, beat them or otherwise bully them, the family said.

"My kids would come home crying every day. They were afraid to go to school," she said.

Berthiaume complained repeatedly to the school, the district, local and state politicians and even the U.S. Department of Education.

She still has a dog-eared file thicker than a phone book of her various fruitless pleas to people for help.

Finally, in May 2005, with the abuse unabated, she planned a protest outside the school.

She made up signs and kept them in her van, waiting for the perfect opportunity.

But fury overtook patience on May 24, when she picked up her kids from school - only to hear that bullies had pounced on her 8-year-old in the bathroom as he relieved himself, yanking painfully on his privates as they called him names, she said.

"I snapped," she said of the day that led to years of tears.

Berthiaume locked her kids in the van and steered toward Huey's front door. Berthiaume said she merely parked the van at the door to protest her kids' treatment; police said she rammed it.

Either way, she got arrested and spent the night in jail. Although acquitted of all but one (simple assault) of the five charges against her, she was sentenced to a year of probation, court records show. The case is the only blemish on her otherwise clean criminal record.

After her arrest, DHS took her kids, then ages 8, 10 and 12, and put them in foster care.

The three bounced around between 15 different placements, according to DHS records. Berthiaume's daughter was moved most, hopscotching between eight foster homes, according to DHS records.

She remembers none fondly.

"A lot of homes hit me, they beat me. Some of the homes, I starved; they would sit down at the table and say: 'You can't sit at this table because you're not part of this family.' So I'd have to eat at school," said the girl, now 14.

The Daily News is withholding her and her siblings' names due to the sexual nature of their alleged abuse.

At one home, Berthiaume's daughter said, a foster parent choked and threatened her after wrongly assuming she scratched a foster baby in the home.

Worst was the teenage boy in one home who pinned her down and fondled her as she struggled to escape in May 2006. She was 10 years old. She and Berthiaume sued DHS for the incident and won a $25,000 settlement from the city and its subcontracted provider in which DHS admitted no fault, DHS records show.

In infrequent phone calls and supervised visits, Berthiaume learned of her kids' struggles in foster care and worked hard to get them back. She earned her GED and took classes in parenting, nutrition and anger management to demonstrate her worthiness as a parent.

Still, DHS kept her two youngest until August 2006 and the oldest until October 2006.

Aside from the assault on Berthiaume's daughter, none of the three reported any maltreatment in foster care, said Dell Meriwether, deputy commissioner of DHS' Children and Youth Division.

Berthiaume said she first learned her sons had been molested two weeks after her eldest came home.

She walked into the boys' bedroom and saw her sons, who had been lying under a blanket, jump up. She thought she had interrupted the eldest trying to molest the youngest, so she called her DHS social worker.

Meriwether said, DHS investigators determined the eldest boy had performed oral sex on his little brother and then threatened him with violence.

"That is a pretty significant incident," Meriwether said.

DHS removed the boy again, and police charged him with a sex crime.

The criminal charges eventually were dropped, but DHS placed the boy, now 16, in a group home for sex offenders where he remains today.

A Family Court judge ordered the other two children to undergo therapy.

Berthiaume said both boys told counselors they'd been repeatedly raped while in foster care, although neither reported the abuse to social workers and DHS has no records of such reports, Meriwether said.

Berthiaume has spent the past three years struggling to rebuild relationships soured from simmering resentments and long absences.

"I love my mom, but I ain't even speak to her now without arguing with her. I have anger issues," Berthiaume's daughter said recently. "This [foster experience] damaged me. I just think of that day [when Berthiaume got arrested at Huey], and I think: If she wanted to get us out, she could have did it in a different way. 'Cause now, we're living a nightmare."

Berthiaume wishes she could take that day back.

"I feel bad, because I take responsibility for my actions," she said, crying. "I take on that burden that I got them placed in the system. If I wouldn't have did what I did, they wouldn't have suffered like they did."

Her house is quiet now.

Berthiaume's husband, tired of the drama, moved out last month.

Her two sons are gone.

DHS refuses to return Berthiaume's eldest son, despite professing, as most social-service agencies do, that family preservation is a top priority.

"Preservation of the family can only be possible when all of the children in the family can be safely maintained," Meriwether said. Further, the child "has not completed his sexual-offender therapy. He still is addressing his mental and behavioral health issues. [And] Ms. Berthiaume has not completed the requisite family therapy."

The eldest boy's "victim" - Berthiaume's youngest son - moved to another state a few weeks ago to live with his biological father, weary of fighting with his mother and rehashing things in interminable court-ordered therapy.

"I live in a four-bedroom house with one child," Berthiaume said. "This has broken my family."

A DHS social worker made a surprise visit to Berthiaume's home for the first time in years last week, shortly after the Daily News began asking DHS about the family.

But Meriwether denied any ill intent.

"Because there's an active child in placement, safety assessment visits should be done every six months. Those were not being done, so your call prompted that," Meriwether said.

But Berthiaume feels unfairly targeted.

"I just wish they would leave my family alone so we can heal from this," Berthiaume said. "They're supposed to be a child-protection agency. They could have left them with me, and they'd be fine. But instead, they say I'm not fit to be a mom, and then they place them with other people who abuse them. They didn't protect my children."

Overburdened systems

Cases like Berthiaume's exasperate Richard Wexler.

Wexler heads the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform, a Virginia-based nonprofit that advocates family preservation.

"In every respect, this is a perfect microcosm of everything wrong with the Philadelphia child-welfare system," Wexler said. "This mother flew off the handle, but did nothing herself to harm her children. So these children were taken from a perfectly safe home only to be abused in foster care."

Fearful of the public criticism that comes after high-profile abuse deaths like Charlenni Ferreira and Danieal Kelly, Philadelphia is too quick to remove children from their biological homes, Wexler contended.

"Philadelphia takes away children at, by far, the highest rate of any major city," he said.

Philadelphia's rate of removal – entries into care divided by the number of impoverished children - is 31.3 children removed for every thousand impoverished children in the county, according to coalition statistics. The national average is 20.2.

"The more you overload your child-welfare system with children who don't need to be there, the greater the likelihood of abuse," Wexler said. "There are two reasons for that: You put your DHS in a position where they are begging for beds. Beggars can't be choosers, so there is an enormous incentive to lower standards for foster parents. The other problem is if you have too many children coming in, you cannot be careful about which foster children you put with other foster children. And one of the biggest problems in foster care is foster children abusing other foster children.

"The only way to fix foster care is to have less of it," Wexler added.

DHS Spokeswoman DeszereeThomas countered that DHS has been successful at reducing its removal rates, saying only 4,988 children were placed in foster homes, group homes, supervised independent living and other settings, as of fiscal year 2009. That's down about 20 percent from a recent high of 6,210 in fiscal year 2005, according to DHS data.

Thomas couldn't quantify how many of those children are in treatment as sex-abuse victims or offenders, saying such information isn't tracked centrally.

But the state Department of Public Welfare, which investigates reports of children abused in foster care, tallied 261 reported incidents statewide of sexual contact between children in foster homes in 2008 and 2009.

National studies suggest the actual incidence of abuse is far higher. For example, youths in foster care are at a higher risk of acquiring HIV, according to a 1999 Washington University study.

"If bad things happen to these children, for the most part, they're unreported," Robinson Lowry said. "And when a foster-care system does a really lousy job, there are really no consequences. These are systems that are usually isolated from public outcry (because of privacy protections). Very often, the only real accountability is when a system gets sued."

A family forever fractured?

Some kids dislike school.

Berthiaume's youngest son has sworn it off forever.

"I will never go back to a public school ever," he said.

Since getting her kids back in 2006, Berthiaume has home-schooled them, the family's faith broken in all public agencies.

She'd like to leave Philadelphia, the city that has brought her so much heartache. But she won't leave her eldest son behind.

So she waits to learn what else she must do to get him back.

"I shouldn't have felt driven to take matters into my own hands. I had this nightmare for five years. Where was the city for me? They're still failing me after all these years," she said of her unending battle to make her family whole. "Five years of people just turning their backs. It feels as though the weight of the world is on us. I'm tired."