Scared straight: Pushing the panic button

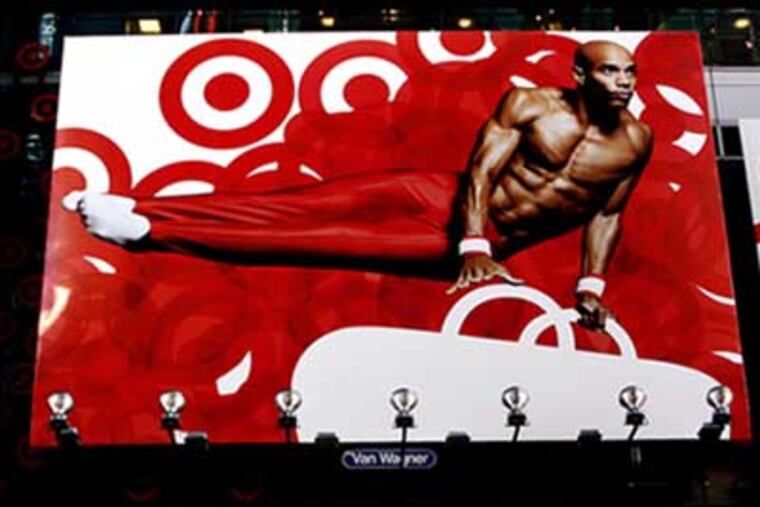

RAY ARMSTRONG, a model whose chiseled body once graced a Target billboard in Times Square, ran out of the Grays Ferry house of his friend, Anthony Williams, on Sept. 27, 2008, stark naked and soaking wet, according to witnesses.

RAY ARMSTRONG, a model whose chiseled body once graced a Target billboard in Times Square, ran out of the Grays Ferry house of his friend, Anthony Williams, on Sept. 27, 2008, stark naked and soaking wet, according to witnesses.

He lay face down in the middle of the street, said, "I am God," and told neighbors not to go into the house because Williams was dead, witnesses said.

No weapon was found inside the home - just Williams' beaten, strangled body, police said.

Almost two years later, Armstrong, now 33, may be pursuing an unusual - and controversial - defense, according to statements made at a pretrial hearing in his case yesterday.

"I plan to file a motion to exclude the gay-panic defense that the defendant has proffered," said Assistant District Attorney Leon Goodman.

Although there's no standard definition of the "gay panic" defense, it rests on the defendant's being so offended or shocked by sexual advances from a person of the same gender that the defendant assaults or kills the victim.

The defense has been posited in several cases around the country, including last year in Illinois, where a man was acquitted of stabbing his neighbor 61 times.

Jon Davidson, legal director at Lambda Legal, a national organization for gay, lesbian and transgender people, said the gay-panic defense could be used as part of an insanity defense or shown as a form of provocation.

"The test of it is, it has to be something that is a sudden and intense passion resulting from a serious provocation," he said.

Sara Jacobson, director of trial advocacy and associate professor at Temple University's Beasley School of Law, said there were no specific provisions for the gay-panic defense under the state criminal code unless it's used in conjunction with insanity or self-defense.

But if it is self-defense, the defendant must believe that force was necessary to protect against death, rape, kidnapping or serious bodily injury, she said.

In her 10 years as a city public defender, Jacobson said, she never saw it employed.

"It strikes me as a defense theory that gets substituted for self-defense when self-defense isn't a good defense theory," she said.

Yesterday, Armstrong's attorney, Joseph Canuso, declined to comment on Goodman's characterization of his defense as "gay panic."

"We provided our doctor's report that Armstrong was suffering an anxiety attack," he said. "As far as what caused all that, that will come out at trial."

If Armstrong does pursue a version of the gay panic defense, the question is: Was Williams gay and did Armstrong know it?

According to friends, neighbors and a video that Armstrong posted online shortly before the alleged murder, the two were longtime pals and Armstrong lived on-and-off at Williams' home for years.

When the original story about the slaying ran in the Daily News in 2008, a woman claiming to be Armstrong's girlfriend "for quite some time" e-mailed that she was angry that there was no mention in the story of "the history of him [Williams] hitting on" Armstrong.

Jacobson, of Temple Law, said if the two had an ongoing relationship for years, it would seem likely that Armstrong would have known if Williams was gay.

"It seems like an odd time to choose to hit on him," she said.

Williams, 37, was loved by his co-workers and customers at Central City Toyota, in West Philadelphia, a job that he began at 18. Shortly before his death he was promoted to service adviser and often worked six-day weeks.

Although Armstrong did have some modeling credits, with stints in Kenneth Cole print ads and iPod TV commercials, his career was far less stable, according to those who knew him through Williams.

Ashley Nichols, a former co-worker of Williams, told the Daily News that Armstrong had "20 different professions."

"His card said model, actor, dancer, stripper and photographer," she said.

On the day of the killing, neighbors said, Armstrong was seen in his Ford Expedition in front of Williams' house, smoking what they believed was a marijuana blunt dipped in PCP or embalming fluid.

Soon after, he began to bust out his windshield with his bare fists, police said.

Neighbors asked Williams to bring Armstrong into his house, which he did. It was only 10 minutes later that Armstrong emerged wet and naked, they said.

In court yesterday, Goodman, the prosecutor, said his office was looking for Armstrong's medical records from the day of his arrest. They believe that he may have been checked in to the hospital as a "John Doe," making it difficult to find records that would indicate whether a drug test had been taken.

Canuso, Armstrong's attorney, said there is "no medical evidence" to suggest that Armstrong smoked or ingested any drugs that day.

He said his medical expert did consider, though, the condition of Armstrong's thinking before, during and after what happened in the house.

"Before this killing took place, [Armstrong] did not act in a normal manner," Canuso said. But he's not pursuing an insanity defense because the medical expert found that Armstrong knew the difference between right and wrong, he said. Canuso noted, however, that a jury could find that Armstrong was acting in self-defense.

Many don't see gay panic as self-defense but rather as a victim-blaming defense.

"Essentially what it's saying is, because he hit on me, I had to kill him," Jacobson said. "It plays on people's panic and fears and negative stereotypes of gays and lesbians."

Davidson, legal director of Lambda, agreed. "Sometimes in these cases people claim they made an advance on me or touched me," he said. "If that were an adequate defense for murder, then there would sure be a lot of heterosexual men in this country who'd be murdered."

The next status date for Armstrong's case is June 30.