A parent in prison: Tough hurdle for a child to clear

My first patient of the day is a 5-year-old girl with hair lovingly manicured with dozens of ballies that click together like a metal pendulum as she bounces around the examining room, oblivious to the intense conversation I am having with her mother.

My first patient of the day is a 5-year-old girl with hair lovingly manicured with dozens of ballies that click together like a metal pendulum as she bounces around the examining room, oblivious to the intense conversation I am having with her mother.

Where is the child's father? I ask. "Away," her mother answers.

This common reply can have many bad implications for the child's health and well-being and is one of the routine questions we ask when we take a social history.

The questions reveal the child's home life and support system, including the type of housing she lives in, the safety of her neighborhood, the school or day-care center she attends, what pets she has (and, of course, the name of each pet), and, most important, who is involved in her life.

With 59 percent of households in Philadelphia headed by single parents or grandparents, I usually ask my next question in a hushed voice, while the child is distracted, or I spell it out: Where's d-a-d or m-o-m?

"Away" is the response I get far too many times. It hangs in the air, like cumulus clouds preceding a thunderstorm.

"Away" is code for "incarcerated." Since more than two million U.S. children have a parent in prison, and Philadelphia's average daily inmate population is close to 10,000, this reply has lifelong ramifications for a child.

Mass incarceration is a very contemporary American phenomenon. In 1980, there were 500,000 prisoners in the United States. In 2007, two million. Although the United States has less than 5 percent of the world's population, it has 25 percent of the world's prisoners. Inmate and civil rights advocates speak against fueling the "prison industrial complex," yet often lost in these discussions are the 2.1 percent of children in the United States who suffer in silence and shame with a parent in prison.

Their difficulties were recently documented in the Fragile Families Study, which followed almost 5,000 children born in 1998 in 20 urban areas and showed that half of children born to unmarried parents and 17 percent of children of married parents had a father with a history of incarceration.

Pervasive poverty, gaps in early development, poor schools, abuse and neglect, unmet mental-health needs, zero-tolerance policies in schools, and overburdened juvenile-justice systems all contribute to the fuel that propels the continued imprisonment of my patients' mothers, fathers, grandparents, aunts, and uncles. Groups such as the Children's Defense Fund's Cradle to Prison Pipeline (www.childrensdefense.org/) and the American Civil Liberties Union's School to Prison Pipeline (www.aclu.org) further reveal some of the root causes of escalating incarceration.

What we know is that African American children are nine times more likely and Hispanic children three times more likely than white children to have a family member in prison.

We also know that the physical and emotional impact on these children can be overwhelming.

Children with incarcerated parents manifest symptoms from the trauma and loss that they experience, such as depression, developmental regression, post-traumatic stress disorder, increased poverty, shame and stigmatization, worsening school performance, stomachaches, headaches, and attachment disorders.

On top of this, they face a higher risk of incarceration, thus perpetuating their parents' cycle. Also, more than 10 percent of incarcerated mothers have their children in state foster care, with an average stay of 3.9 years.

Back in the examining room, I ask: "How long has he been away?"

"Four years," her mother answers, emotionless, eyes diverted to the floor. "They tell me that when other fathers pick up their children at her day care, she cries and hides behind one of the workers."

I reflexively apologize for her suffering and offer her resources for families with incarcerated parents, including the Pennsylvania Prison Society's Services for Kids With Incarcerated Parents (www.prisonsociety.org) and the Angel Tree Program (www.angeltree.org/), which links places of worship with families affected by incarceration. I make a follow-up appointment in three months to check on the girl's development and lovingly rub her head, causing her ballies to resume their distinctive clicking.

Later, I drive west up Erie Avenue past Front Street after leaving St. Christopher's Hospital for Children and reflect on what the future holds for my little patient. With the windows cracked to let the cool breeze in, I am awakened from my desolate thoughts by the laughter of children playing double dutch and tag on the sidewalks around me.

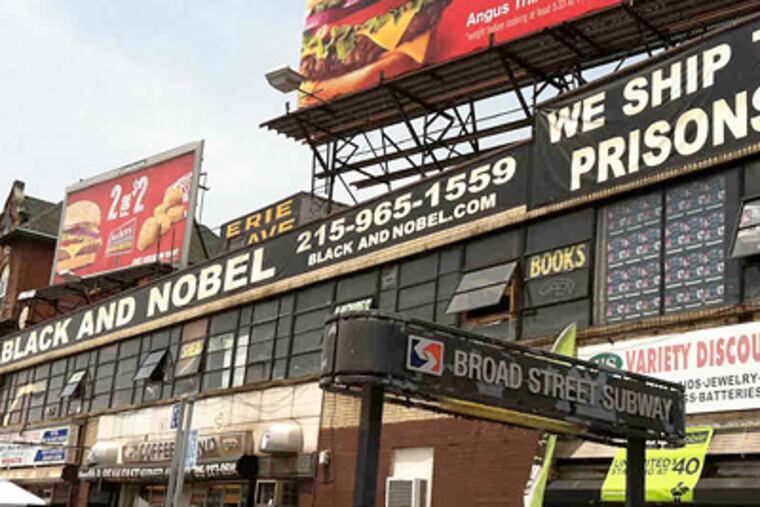

As I pass Broad Street, I glance over at the large bookstore on the northwest corner, Black and Nobel, where vendors are selling CDs, and gospel music resonates.

Then I notice a large sign emblazoned on the side of the store that states: "We ship to prisons."

Yes, we do.