Author of Depression-era note on church tub identified

His grandson figures Louis J. Volpe must have been 36 on that January day in 1933 when he scrawled a note on the side of the bathroom tub he had just installed at Christ Church.

His grandson figures Louis J. Volpe must have been 36 on that January day in 1933 when he scrawled a note on the side of the bathroom tub he had just installed at Christ Church.

And that Volpe must have believed his message would be found someday. And more, that his 17-word tale of Depression-era survival would still hold meaning.

Volpe, now dead about 40 years, turned out to be right on both counts.

On Monday, news about the discovery of his missive appeared in The Inquirer - and Volpe's descendants telephoned and e-mailed one another, elated to hear from a family patriarch across the distance of nearly 80 years.

"It was like a voice from the grave," said Richard King Sr. of Ocean City, N.J., Volpe's grandson. "He'd be thrilled to know it was there."

Louis Volpe was no celebrity or high public official. He was a plumber, the son of an immigrant. When the note was written, he was living with his wife, Ella, and their three children at 1847 S. Sartain St. in what was Italian South Philadelphia. His life revolved around his trade, his church, and his family.

His name sprang into the news on Monday, after Christ Church officials outlined their discovery at the church's Washburn House in Philadelphia. The note, written in pencil, had been hidden behind a wall and revealed during a renovation.

"Tub set 1-9-33 by Louis J. Volpe," the message said. "This work kept two men from starving during the Depression."

Those words captured the reality of the Depression, a time when Philadelphia hospitals reported cases of starvation. In 1931, two of every five Philadelphians were unemployed or trying to survive on part-time work. Bread lines were common.

Bruce Gill, who serves as the rector's warden, equivalent to chairman of the church board, found the note when he and a colleague went searching for a water leak.

"It's like putting a message in a bottle," said the Rev. Susan Richardson, the assistant minister. "Putting it by the pipes was smart - where it could be seen. He did the best possible job of putting that lid on the bottle."

Volpe survived the Depression, though it wasn't easy. Family members said that in those years he took work wherever he could find it, traveling as far as the Poconos.

When the war came in 1941, Volpe, then in his early 40s, worked in the shipyards. During the 1950s, he annually took the whole family to Ocean City, traveling by train for a two-week summer vacation.

Volpe never owned a car - a Depression-era thriftiness that stayed with him.

He belonged to the Sons of Italy and, like his friends and neighbors, was a devoted Roman Catholic. His brothers also worked in the trades: Albert was a plumber, John an electrician, Frank a bricklayer.

"My father and my uncles, they always used to say they could build their own house," said Elaine Volpe Dych, Louis Volpe's 72-year-old niece and the daughter of Albert Volpe. "They were very close, the brothers."

They knew tragedy: Another brother, an electrician named Michael, died in his 30s, and a sister, Marie, died in childbirth at 21.

Dych, a retired nurse who lives in Springfield, Delaware County, said she wasn't surprised that her uncle had left a note for the ages.

"My Uncle Louie was a perfectionist," she said. "This is typical of what my Uncle Louie would have done."

Dych, who is compiling a family history, described her uncle as "a typical, dominant, Italian male. My father and his brothers were all alike. They ran the household."

Dych's sister, Janet Carrelli, 74, of Northeast Philadelphia, saw three sons become plumbers. She, too, well remembers her Uncle Louie.

"He was a tough guy," she said with a laugh. "When we went to the house, we didn't move."

The brothers came from hardy stock. Their father, Michael Volpe, had emigrated from Italy in 1885. He operated a barbershop on Mifflin Street.

From there the family grew and spread, to the Pennsylvania suburbs and New Jersey. Two of Volpe's descendants became nuns. Others continue to work as tradesmen.

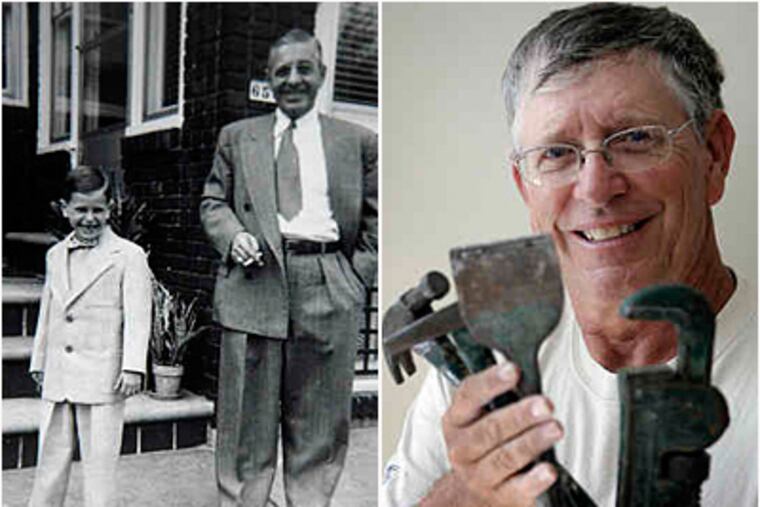

King was close to his grandfather, living with him for two years as a child, and following him into the trades. In fact, King said, his grandfather set his course in life.

"I was just a dumb kid out of high school," said King, who graduated from West Catholic in 1965. "He says, 'You're going to be an electrician.' My reply was, 'How much do they make?' At the time, the rate was $5 an hour. I was like, 'Show me that job!' Minimum wage was maybe $1.25.

"I was just smart enough to know that he knew better than me."

King spent 40 years as an electrician. He's now 63 and retired. He still has his grandfather's tools.

His mother, Teresa, was one of Louis Volpe's three children, along with Michael and Rita. All three are deceased.

"Even as a kid, I could tell he was, 'Put your nose down to the grindstone, go to work, come home.' He wasn't defined by his job, he was defined by his family," King said. "You could always tell he was grateful to have what he had."

His grandfather died in 1968, almost 72.

King said he was surprised his grandfather's message had been discovered, but not that it existed. As an electrician, he'd signed his work in similar fashion over the years.

"In the building trades, you always know that whatever you put in is going to get torn out," he said. "If he was alive today, he'd tell me, 'That's good plumbing. It lasted.' "