Library Company of Philadelphia offers treasure trove of black history

The mid-1960s facade of the Library Company of Philadelphia belies the age of what's inside. The company was founded as the nation's first subscription library in 1731 by - surprise! - Benjamin Franklin and members of his intellectual circle. Used as the unofficial Library of Congress during the period when Philadelphia was the nation's capital, its tony beginnings have often linked the collection to a blue-blooded elite.

The mid-1960s facade of the Library Company of Philadelphia belies the age of what's inside. The company was founded as the nation's first subscription library in 1731 by - surprise! - Benjamin Franklin and members of his intellectual circle. Used as the unofficial Library of Congress during the period when Philadelphia was the nation's capital, its tony beginnings have often linked the collection to a blue-blooded elite.

But a few years after its mid-1960s move into its current Locust Street building, the library mounted a landmark exhibition illuminating a very different aspect of America's past. It was called Negro History 1553-1903, and the nation had never seen anything like it.

In 1969, then-director Edwin Wolf 2d, in partnership with the neighboring Historical Society of Pennsylvania, presented what Inquirer critic Victoria Donohoe at the time called "the largest Negro-history exhibition ever."

"They were way ahead of most places, which waited till the 1970s to discover African American history," said Kathleen Hulser, senior curator of history at the New-York Historical Society.

"It was very forward looking," agreed Gary Nash, professor emeritus of American history at the University of California, Los Angeles. "African American studies was just beginning to take off."

But the vast collection of African American material was not created in response to an academic trend; rather, it was already there, amassed over the years, and needed only to be identified. And cross-referenced. And cataloged.

"When people were paying more attention to this field, our directors and librarian at the time thought, 'Hmmm, I wonder what we've got,' " said library director John C. Van Horne.

Because of the show, the Ford Foundation gave the library $110,000 (more than $600,000 in today's dollars), enabling it to hire Phillip Lapsansky, now its curator of African American history, to spend three years "stack ratting" - looking for relevant material throughout its enormous collection.

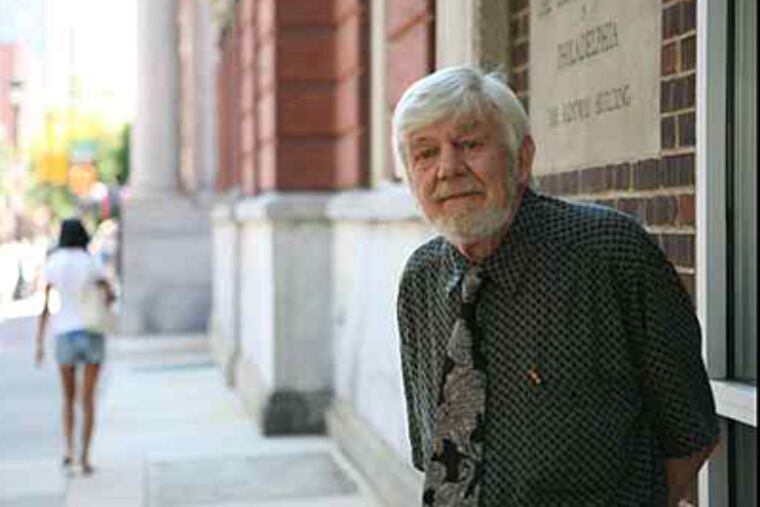

The work of Lapsansky, now 69, and his colleagues spawned an exhaustive catalog titled Afro-Americana, 1553-1906, which indexes more than 16,500 items. He remembers it as an exciting time for academics.

"People were asking new questions," he said. "They wanted to look at things differently. They wanted to look at things that hadn't been looked at."

After the success of Negro History, the library mounted a spin-off exhibition in 1974 called Women, 1500 to 1900. Both shows revealed how the collection - with enough funding - could be mined for specific content to respond to academic trends.

For Lapsansky, a Washington state native who had been involved in the civil rights movement in Mississippi from 1964 to 1966, working on the Afro-Americana catalog project was a natural progression.

"I came here with a preexisting disposition, you might say. I took the job because it spoke to what I wanted to do, and I stayed because it continued to do so."

Moving from the segregated South to a purportedly integrated North was not as smooth as he expected.

"Having lived in Jackson, Miss., segregated communities were, of course, no surprise. But it was a bit of a surprise up here - totally de facto," he said.

Lapsansky noted the progress of recent decades, particularly in the realm of government, but he said that African American representation within his own field remains stunted.

"People of color do come to study here, but not nearly in the same relationship, or numbers or proportion as whites," he said of graduate-level researchers. "Part of that is that there are still not that many [African Americans] engaged in liberal arts.

"When you're talking about a class of people that are first- and many times second- or third-generation college graduates, they're looking for the more economically advantageous programs and degrees. You want to be a historian or an accountant?"

For those who do hold an interest, the collection astounds. In the print collection one can find a 16th-century engraving of slave labor one moment and a photo of a 20th-century black laborer with white coworkers under the Frankford El the next.

"We've had, since in the beginning, a building up of any aspect that touched on the black experience," said Van Horne.

Back in 1792 the directors commissioned a painting by Samuel Jennings that is prominently displayed in the main reading room. Liberty Displaying Arts and Sciences, or The Genius of America Encouraging the Emancipation of the Blacks depicts Liberty imparting knowledge to a group of African Americans. It spoke to the Quaker directors' abolitionist leanings.

But printed materials are the core of the collection: slave trade accounts, the economy of slavery, abolitionist literature, and documents from Philadelphia's free black community, the largest in the nation.

The library's African American History program also funds four research fellowships a year, and such public programs as its annual Juneteenth event.

At the moment, the library is exploring the possibility of digitizing the cataloged items in partnership with a publisher, a notion that excites Nash, who has written extensively about race and American history.

"It's a great step forward to democratizing access," he said.

And the collection continues to grow. The 1970 catalog was out of date immediately after its publication, as was its 1995 supplement.

When asked if it could be compared to other renowned collections - say, New York's Schomburg Center - Nash speculated that while the Schomburg would be much stronger on the 20th century, in 17th- to 19th-century materials the Library Company could very well be No. 1.

Nash credits Lapsansky with continually refreshing the holdings, calling him "a hawkeye when it comes to Afro-Americana materials coming onto the market."

For his part, Lapsansky frowns on the notion of comparing collections.

"That's not the point. We have no interest in that. To think of us in competition is just ridiculous. It's not the way it works and it's not the way we think," he said, before citing Temple University's "terrific" Charles L. Blockson Collection. "Let's talk about how we complement those collections, as they would be complementing ours."

"What is a library?" he said. "A collection of answers awaiting their questions. That's our orientation. That's how we think."

Library Company of Philadelphia

1314 Locust St., Philadelphia 19107

Hours: Reading room and gallery, 9 a.m. to 4:45 p.m. Monday through Friday; print room by appointment.

Information: 215-546-3181 or www.librarycompany.org.

EndText