WHITE HAVEN, Pa. - Brian Dunnigan is a blacksmith by trade who dwells in an old mining patch town with no street lights.

Breakfast is eggs scooped from the chicken coop out back, and he's thinking of acquiring two goats for milking.

Dunnigan doesn't just love history, he lives it.

And the 64-year-old West Hazleton native and Vietnam veteran would not want to spend his retirement any other way.

After years of volunteering as a tour guide and lecturer at the state-owned Eckley Miners' Village near Freeland, Dunnigan decided to immerse himself in the place.

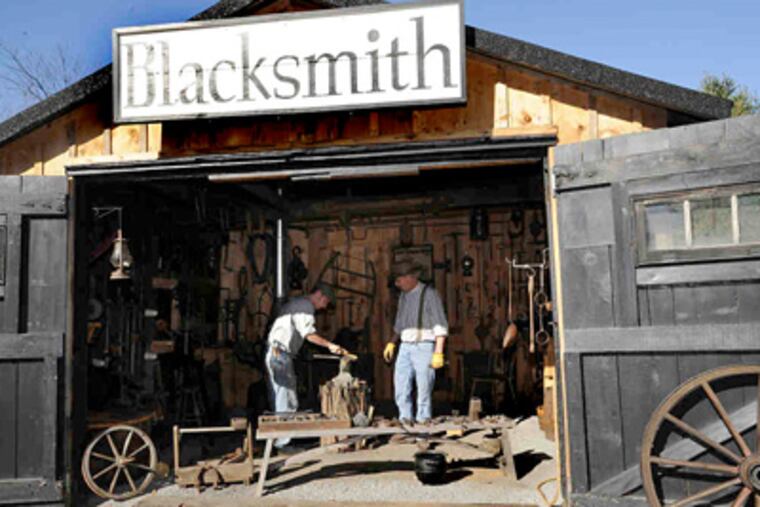

He moved out of his family home into one of the museum's old miner houses last year and has set up a blacksmith shop in the nearby garage to teach visitors about the trade and display the antique tools he has been collecting since he was young.

Several other mining homes are rented by private citizens for roughly $100 per month, with the agreement that inhabitants will respect the historical character and park their vehicles elsewhere when visitors are around.

"It's just a little place where time stood still. It suits me just fine," Dunnigan said as he created a primitive two-pronged fork in his shop.

While he is blacksmith Dunnigan to the general public, he has modern amenities inside the mining home. That includes indoor plumbing, contrary to the impression left by the town's numerous outhouses.

He has also figured out a way to get his favorite television channels. He walks past the six chickens nibbling grass in his yard and points to an old-fashioned well.

"If you look in the well, you'll see the secret of it all," Dunnigan said, peeking at a satellite dish stashed inside.

"That's what it's all about," he said, beaming at his ingenuity.

His interest in blacksmithing was sparked as a boy, when he watched a blacksmith who worked at the old Price's Dairy in Hazleton, which relied on horse-pulled wagons to deliver milk.

"That always stuck in my mind through the years, to see that guy fabricate whatever they needed for the wagons," Dunnigan said.

After the military, Dunnigan worked as a "jack of all trades" for a coal mine company that operated a coal breaker that once stood by Eckley. The town now has a large model of a coal breaker built by Paramount Pictures for the 1970 movie The Molly Maguires, starring Sean Connery and Richard Harris. Part of the movie was filmed at Eckley.

Working at the real breaker, Dunnigan said he sometimes pictured living in Eckley.

"Back in the '70s, the town was full of people," he said.

When the mines died, Dunnigan took a journeyman's apprenticeship as a millwright, learning a gamut of industrial skills. He worked locally and then in Georgia before returning to the area to retire and become a blacksmith.

Blacksmithing fascinates Dunnigan because he can transform a little block of iron into something decorative or useful - hooks, lantern holders, letter openers, utensils.

Holding a small iron block with tongs, Dunnigan thrusts the piece into the hot coals until the metal turns red.

Wait too long, and the block will melt beyond use, something that occasionally happens when he is engrossed in conversation with museum visitors.

He props the red-hot metal block on an anvil and bangs it with a mallet, elongating the iron in a process known as "drawing out."

"This will probably stretch out almost three times its size. You could get that much stretch out of that piece of metal," Dunnigan said.

The iron is heated and hammered over and over until he coaxes it into the desired form. A rapping sound fills the shop as he works the iron.

An old blacksmith advised him, "Let the fire be your friend." In other words, get the iron back in the fire when it starts getting too cool.

"When it starts cooling, you could beat your brains out. You will subdue the metal, but you're wasting your energy. When it's hot, it's just plastic, so you can just move it right along," he explained.

He pulls out a dragon head formed on the tip of an iron bar, saying it may become the handle of a cane or fire poker.

"It's pretty interesting to see what you can fashion out of iron," Dunnigan said.

One of his sons, 19-year-old Keenan, is often at his side in the shop and plans to attend the John C. Campbell Folk School in Brasstown, N.C., to receive formal training in blacksmithing.

Blacksmiths can make a living today making ornamental or restoration hardware and decorations for historic sites, as renovators of old houses or Civil War re-enactors, including those who come from other states to camp out at Eckley during special events.

Dunnigan eventually wants to start a blacksmithing class at Eckley.

The exteriors of several neighboring mining houses are being restored, and he envisions them filled with people who have other throwback skills, maybe a shoemaker or rug maker.

"Hopefully they'll find money to get the interiors of these homes done, and we can get people interested in this type of lifestyle to rent," Dunnigan said.

"This is not for everybody. It's very isolated here, very peaceful. I really enjoy it here."