Translating Philly-ese

There's more than one dialect, and they're ever-changing. It's old, it's new, it's white, it's black, and if you sling that slang incorrectly you'll hear about it.

Youse guys sure have an interesting way of talking.

But once you've dispensed with the obvious - that is, you've waded through the wooder, finished off that hoagie, and checked your attytood - the question remains: What is the Philly dialect, really? How do you speak Philadelphian? And what, exactly, is a jawn?

Tracking down answers turns out to be a complex proposition: Not only is there more than one dialect in Philadelphia, but those dialects are evolving, according to linguists.

So, your dialect is not your grandfather's - and it may not be your neighbor's either, as aspects of white and African American vernaculars diverge.

Add to that the popularization of local slang, terms like drawlin, salty, and young boul, and even the experts - Philadelphia teens - have trouble keeping up.

"We always [use slang], but trying to explain it or spell it, I honestly don't know," said Maria Santos, 15, a student at Delaware Valley Charter High. She does know this, though: "If you use the wrong slang, people laugh at you."

The forces driving Philly-speak may be different than you think. Linguistically, Philadelphia isn't part of some Northeastern bloc, nor is it merely a "sixth borough" of New York.

Rather, it's considered part of the Midlands, a dialect region that starts here and stretches west through Missouri, said Josef Fruehwald, a native Philadelphian who studied the dialect as a doctoral student at the University of Pennsylvania.

That Midlands heritage comes with certain perks: Unlike many East Coast dialects, we manage to pronounce the r sound in words like car. And unlike, say, New Englanders, we have the flexibility to use anymore as a positive - as in, "Traffic's a mess on the Skook'l anymore."

But Fruehwald said pronunciation is where our dialect is really unique.

Last year, Fruehwald and Penn linguist William Labov published a study showing that the white Philly dialect is shifting away from Southern influences and toward the Northern dialects heard from western New England to the Great Lakes.

"When I try to tell people what the Philadelphia dialect sounds like, I tell them to listen to the sound ow, the sound that shows up in out, down or house," he said. "It's a classic Philadelphia sound, more like day-awn. But people born after the '50s and '60s tend to just say down, the way the rest of the country does."

That's not to say we're becoming assimilated.

As some Philly language quirks have disappeared, others have emerged, the study found. For example, compared with Philadelphians born a century ago, residents no longer fight; they foight. A snake in the grass, by their telling, sounds more like a sneak. And while they might let one day pass in standard fashion, they modify its plural into deez.

Why that's happening, and what will happen next, is less evident.

"A lot of these things are, when it comes down to it, cultural changes," Fruehwald said.

Those changes aren't uniform, either.

That study focused on white Philadelphians, because of the data the researchers had on hand.

Some studies have shown white and African American vernaculars diverging, said Ben Zimmer, a linguist, lexicographer, and language columnist for the Wall Street Journal. But, he added, such research often focuses on vowel sounds. Other aspects of dialect, such as word choice, may paint a different picture.

"There are lots of other possibilities for crossover between white and black, in terms of having a distinct Philadelphia linguistic identity that transcends racial or ethnic backgrounds," he said. "For instance, African American slang that might be popularized through hip-hop can appeal to audiences regardless of race."

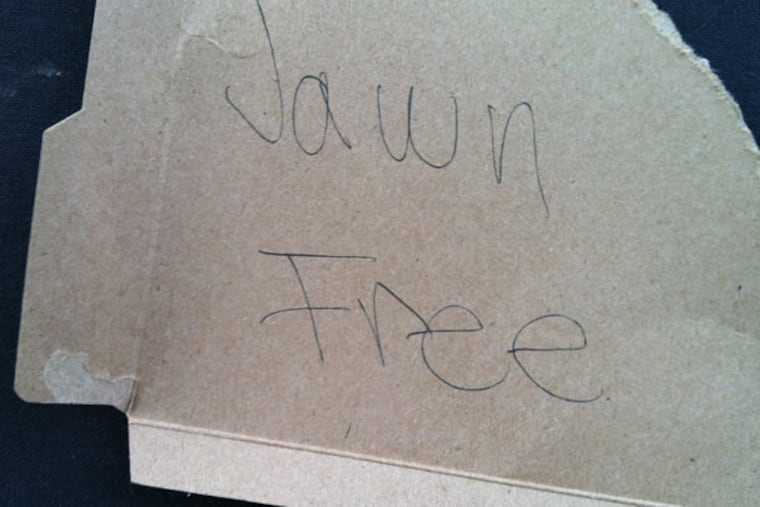

Enter jawn.

That word, at perhaps 20 years old, has proved surprisingly durable, yet resolutely local.

"A lot of my students who grew up in Philadelphia don't know that others don't know that word," said Muffy Siegel, a Temple University linguist who has written academic papers on the usage of like and dude.

"Students have gotten into big fights about what jawn means," she added. "Men will tell you, 'Of course, you can use jawn to refer to a woman.' A lot of women would say, 'You'd better not.' And I certainly wouldn't, because it does sort of mean 'a thing.' "

It turns out that jawn is just the best known of a number of highly malleable Philadelphia slang words.

Another, drawlin, was up for debate in the food court of the Gallery mall on a recent afternoon.

Jahnasia Jones, 14, a student at Murrell Dobbins CTE High School, translates it thus: "You drawlin means 'You playing too much - like, stop, for real.' We also say, 'You irkin.' "

But her friend, Isaiah Dunbar, 15, said the word might also signify amusement, "like, 'You funny.' "

Most linguists agree that jawn is a cognate of joint. But when it comes to drawlin, there's not much to go on, Zimmer said.

"If it originates in oral use, it can become popularized in a community without having ever much of a written record," Zimmer said.

And by the time a lexicologist gets interested in a slang word, its meaning may have changed.

Zimmer described seeing the term young boul, as applied by an older male in a relationship to a younger male, to imply a degree of protectiveness.

"A word like that, which seems pretty specific to Philadelphia, can serve this important social role of creating bonds between members of the community," he said.

But, constantly volleyed back and forth among teens, young boul has become irksome (or, rather, irkin'). It's often used condescendingly, to allege immaturity.

"I hate being called a young boul," Isaiah said. "We're the same age!"

By comparison, Lyceifa Dicks, 15, helpfully told a reporter, "We'd call you oldhead."

Then there's salty - or saldy or sauty, depending on whom you ask - a very Philadelphian word for a very specific type of embarrassment.

"Salty is: You thought you were right, but you're wrong," Nisha Michelle, 15, explained.

Siegel said it's not surprising that Philadelphia's youth slang is ephemeral.

"Inner-city slang, or the slang of any group that feels oppressed, that slang might change even more quickly, because as soon as the mainstream takes it over, it's not unique anymore," she said. (At that point, Philly teens translated, it would be dead or chalk - that is, irrelevant.)

And as for slang that doesn't die? It can become a permanent part of our lexicon.

To this day, many Philadelphians stick to the pavement rather than venturing onto the sidewalk, and raise hell on Oct. 30, "Mischief Night." They never go to the beach - they head down the Shore.

And they all share the most Philadelphia word that ever was: hoagie.

One etymology researcher attributes its origin to a local restaurateur who, in 1936, unveiled a sandwich called the "hoggie" - a comment on the appetite required to consume one.

Zimmer said the endurance of hoagie, and the many other Philadelphianisms not mentioned here, is more than just linguistic novelty.

They're also testaments to prized Philadelphia obstinacy.

"There are forces for homogenization: the fact that Subway is a popular chain, and presumably popularizing the term sub in places that might have used hoagie or hero," he said. "But people can really hold on to what they grew up with sometimes as a point of pride: 'This is how we speak in Philly.' There's a pride in having a distinct way of using language."

215-854-5053