It's hard to imagine how anyone could get riled up by a Hallmark card showing a serene mom clutching roses, but that's only if you don't know the story of Anna Jarvis of Philadelphia.

She's the person most credited with turning the second Sunday of May into Mother's Day, which this year celebrates a milestone: 100 years.

In her view, the holiday she crusaded for - a day she'd hoped would be reverential and contemplative - was ruined by commercialization as early as the 1920s.

By some accounts, she spent the rest of her life trying to take back, actually rescind, Mother's Day.

"A printed card means nothing except that you are too lazy to write to the woman who has done more for you than anyone in the world," Jarvis reportedly said. "And candy! You take a box to Mother - and then eat most of it yourself. A petty sentiment."

She's said to have called florists and the makers of greeting cards and candy "charlatans, bandits, pirates" and even termites.

The notion of a Mother's Day was initially a "fairly radical idea," says Andrew Phillips, curator at the Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library and Museum in Staunton, Va., where an exhibition this month celebrates President Wilson's first proclaiming Mother's Day in 1914.

But it was part of the broader movement toward women's rights and equality in the 1860s and '70s. Julia Ward Howe's 1870 poem "A Mother's Day Proclamation," coming not long after the carnage of the Civil War, was really a call for peace. (You may know Howe for writing "The Battle Hymn of the Republic.")

Anna Jarvis' mother, Ann Maria Reeves Jarvis, was an activist who offered medical care to soldiers of both sides during the war, mainly in West Virginia. She organized Mothers' Day work clubs, aid organizations that tried to lower infant mortality, among other public health projects.

It was her death on May 9, 1905, that led to what we know as Mother's Day.

Around the second anniversary of her mother's passing, Anna Jarvis honored her at a small gathering of friends at her home in Philadelphia. And on May 10, 1908, Jarvis arranged for 500 white carnations, her mother's favorite flower, to be handed out in a ceremony at the Grafton, W.Va., church where her mother had taught Sunday school.

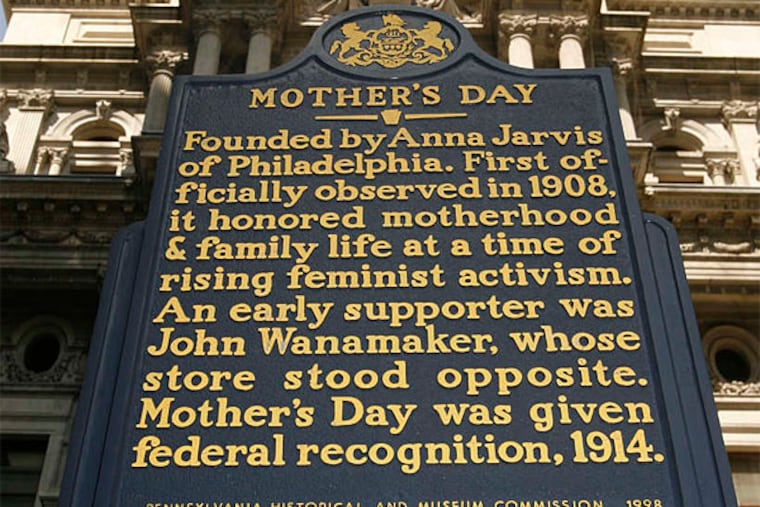

Some consider that event the first Mother's Day (including the city of Philadelphia, where a historical marker on Market Street near City Hall notes Mother's Day's 1908 founding), but the campaign for an official Mother's Day would slowly build, starting with proclamations by communities in West Virginia, then spreading to other cities and states. West Virginia made it a holiday in 1910. Jarvis, who started a group called Mother's Day International Association Inc., and others lobbied government officials by writing thousands of letters.

And on May 8, 1914, the U.S. Congress, in a joint resolution, established the second Sunday of May as Mother's Day. The next day, Wilson issued a proclamation. The document urged Americans to display flags "as a public expression of our love and reverence for the mothers of our country."

Jarvis thanked the president ("Your Excellency") in a letter. Mother's Day, she wrote, would be "a great Home Day of our country for sons and daughters to honor their mothers and fathers and homes in a way that will perpetuate family ties and give emphasis to true home life."

The holiday Anna Jarvis worked so hard for was supposed to be about sentiment, not profit. She started complaining almost right away about how the day was being misinterpreted.

By the early 1920s, Hallmark and other companies had started selling Mother's Day cards.

Jarvis, meanwhile, organized boycotts and threatened lawsuits to try to stop the commercialization. She crashed a candy-makers convention in Philadelphia in 1923. Two years later, she did the same at a confab of the American War Mothers, which raised money by selling carnations, the flower associated with Mother's Day.

That time, Jarvis was pulled away screaming and arrested for disturbing the peace.

She died - penniless and in a sanitarium - in 1948 and was buried in West Laurel Hill Cemetery in Bala Cynwyd. The card market lived on.

At the Hallmark Visitors Center in Kansas City, Mo., where there's another Mother's Day exhibition this month, a wall adjacent to a display case of Wilson artifacts shows off Mother's Day cards from the Hallmark archives. A lot of those early Mother's Day cards reflected "women's work" around the house. Another prevailing theme: "a lot of floral throughout the decades," Hallmark historian Samantha Bradbeer says.

Something else you notice is "Mother." Not "Mom," which didn't become common on Hallmark cards until the 1980s. But those early Mother's Day cards were targeted at adult buyers; cards marketed to children started appearing in the 1940s and '50s.

By the 1960s, the Hallmark moms finally started moving out of the kitchen and into the workplace. One card from that era depicts a woman at a desk behind a typewriter. Are we to conclude she's a secretary? Maybe, but the briefcase on the floor might suggest otherwise.

More casual sentiments and humor in Mother's Day cards came along in the 1960s, such as cards featuring characters from the Peanuts comic strip.

Still, if Hallmark cards are a barometer, we regard dads differently from moms. There's still far more humor found in Father's Day cards. About four-fifths of Mother's Day cards fall into the "loving" category.