Art on track aims to brighten commute, neighborhood

Most commuters on an outbound Chestnut Hill West SEPTA train Monday afternoon didn't look up from their phones as the crumbling landscape of derelict warehouses, rusty trestles, and overgrown vegetation flickering by their windows suddenly turned safety orange, then magenta, then ectoplasm green - an effect that might best be described as postapocalyptic psychedelic.

Most commuters on an outbound Chestnut Hill West SEPTA train Monday afternoon didn't look up from their phones as the crumbling landscape of derelict warehouses, rusty trestles, and overgrown vegetation flickering by their windows suddenly turned safety orange, then magenta, then ectoplasm green - an effect that might best be described as postapocalyptic psychedelic.

And when a passenger who had come to view the painted landscape disembarked at the deserted North Philadelphia station to head back to Center City, neighborhood kids passing on bikes asked knowingly, "You get the wrong train?"

Soon, though, droves of art-hungry tourists may be making the same pilgrimage.

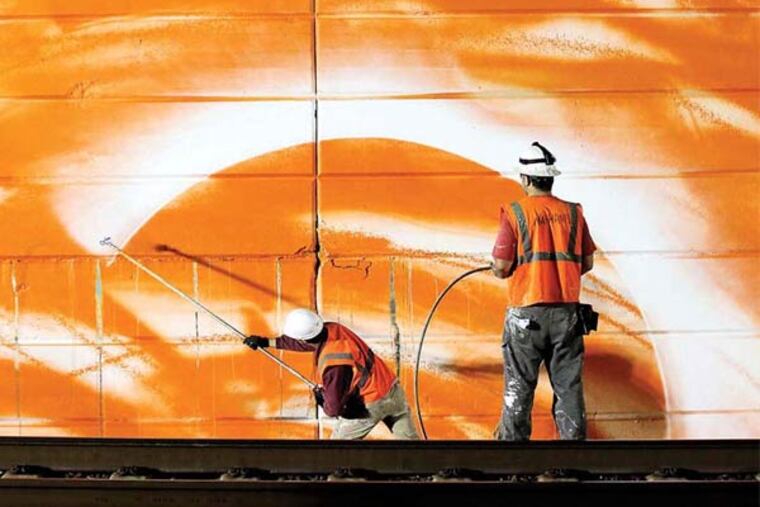

For the price of a SEPTA ticket (Trenton trains offer the same view), Amtrak fare, or New Jersey Transit Atlantic City ride, passengers will get a high-speed tour of German artist Katharina Grosse's Psychylustro, a series of seven paintings for the city's Mural Arts Program along a stretch of Amtrak rail between 30th Street and North Philadelphia.

It's far from your typical Mural Arts project - not just because of its cost (nearly $300,000, funded by a patchwork of grants) and unprecedented logistical challenges (it required close to 40 contracts), but also because Grosse's work is more often seen in the context of museums, galleries, and art magazines. Psychylustro reflects Mural Arts' most significant foray into the fine-art realm to date.

"It's quite a departure for us," said Jane Golden, executive director of Mural Arts, which, though recognized as a force for community engagement, has also weathered criticism for works seen as obvious, folksy, or mawkish. "As we think about Mural Arts in the 21st century, and as we think about the future of painting in public spaces, abstraction, conceptual work, and installations are interesting to us."

That doesn't mean the end of Mural Arts as we know it, said Golden, who days earlier helped dedicate one in Germantown about mothers who had lost kids to violence. But lately Mural Arts has collaborated with visiting curators to refine its artistic vision.

"This is not mission drift," she said. "It's about: Can you do really good art, have a really good process, and have an impact?"

In this case, the site of impact would be the blight-lined, graffiti-scrawled rail corridor through North Philadelphia.

Though only part of it is doused in pigment, arguably the whole troubled stretch of the city is Grosse's subject. She had hoped to tackle the Divine Lorraine Hotel or the Reading Viaduct; when those were nixed, Golden mentioned her dream of turning the rail corridor into a linear gallery.

"It became a perfect answer for how Mural Arts could transcend its own practices, to create something that's more than a mural, that's really a large-scale installation," curator Elizabeth Thomas said.

Three audio tracks and 25,000 seat-back cards will mediate the experience while the painting lasts. The works, made from interior house paint, are designed to be erased by the elements over time. (Some have wondered whether graffiti writers may expedite that process, despite a longstanding detente. Mural Arts contacted those whose work might be covered over and met little resistance.)

Amtrak, which had been in talks with Mural Arts for years about a potential collaboration, also readily agreed, supplying watchmen and offering late-night shifts when tracks weren't in use.

Though the works appear as a series of expressionstic gestures, Grosse's own hand isn't directly seen. She selected the sites and made detailed sketches, then turned the project over her two assistants and six Philadelphia artists.

So, late Sunday night, the group huddled around a creased sketch as Beate Slansky, one of Grosse's assistants, struggled to relay instructions. It wasn't enough for the workers to replicate Grosse's vision: They had to "embody" it.

"There, the slope of the hill is almost perfect, only the mark needs more power," Slansky pointed out. "Katharina spoke about windshield wipers: Let this movement come from the whole body."

This degree of delegation is a new mode of working for Grosse, who once described her expressionistic, gestural works as indulging "in exuberance and aggressive energy without killing anybody."

But Grosse was excited by the different energy each artist contributed.

She also recognized a common ground between her own practice and Mural Arts': "The idea of transformation and transforming my surroundings I always have had in my work," she said.

Though her work is abstract, the corridor's vacant buildings and grimy infrastructure - highlighted in shocking hues - have inevitably become its subject matter, she said.

"My painting . . . is coming into an area where a lot of questions are being asked - and it kind of heightens your awareness. If a strange thing comes into your life, it acts as a spotlight. It compresses the emotions."

Grosse hopes the work will foreground the landscape; Golden hopes it will go further than that, to catalyze its renewal.

But painting over a problem - as Mural Arts' last big abstract installation, Haas & Hahn's color-blocks across a blighted stretch in Germantown, inspired some to remark - will not make it disappear.

Still, it could be a start, said Andrew Frishkoff of the community-development organization Local Initiatives Support Corporation.

"Many of us have thought that it would be great if someone beautified the corridor as seen from the trains, and this is one answer to that aspiration," he said. "A slightly smaller number of us have wondered what it would take to revitalize those places. . . . This artwork is not really the answer to that question, but I hope that it inspires more people to develop some feasible answers."

215-854-5053

@samanthamelamed