Finding a new career in his zeal for maps

SAN FRANCISCO - Beyond the iron gates at 1435 Grant Ave., in the heart of San Francisco's North Beach neighborhood, worlds await. Or, more precisely, intricate and painstaking charting of the world as we have known it. More than just paper-and-ink renderings, really, you'll find the story of our physical and emotional landscapes, writ both large and very, very tiny.

SAN FRANCISCO - Beyond the iron gates at 1435 Grant Ave., in the heart of San Francisco's North Beach neighborhood, worlds await. Or, more precisely, intricate and painstaking charting of the world as we have known it. More than just paper-and-ink renderings, really, you'll find the story of our physical and emotional landscapes, writ both large and very, very tiny.

To call Schein & Schein an antique map and print shop fails to capture the scope of its breadth and appeal. What spouses Jimmie and Marti Schein sell are history and memories, guides to where we came from, and, perhaps, to where we're going.

As soon as you cross the threshold, you feel transported.

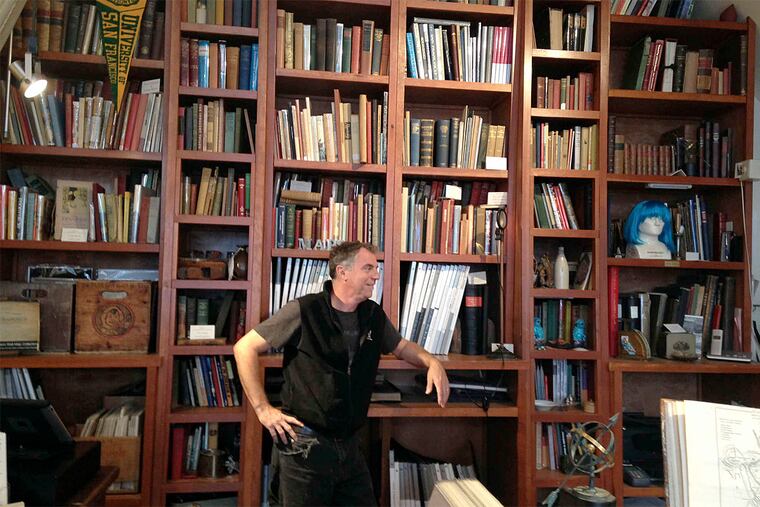

It's not just the burnished floor-to-ceiling shelves crammed with oversize atlases that can be plucked from on high only by way of ladders set on tracks and rollers. Nor is it the air of orderly chaos - maps and vintage photos in protective sleeves sprouting from old produce crates, or rolled into tubes, or placed in thin-drawered desks.

There's an air of reverence and preservation that permeates the place, personified by the hyperintense, fast-talking, infectious zeal of Jimmie, 52, who found his way in life through the collection, study, and, ultimately, sale of maps.

Here's a guy who for years, as manager of a music logistics company, toured with rock and jazz artists, doing everything from tuning instruments to driving a truck. But he'd much rather enthuse about German lithographers Charles C. Kuchel and Emil Dresel than tell stories about hanging with Metallica and Miles Davis. On the road, Jimmie spent his $800-a-week stipend hunting down vintage maps at antiquarian bookstores from Auckland to Zurich and many an American town.

When, 12 years ago, he decided the romance of the road was waning, he took a buyout from his company and donned his rectangular spectacles to share his passion with the public.

Even in an era when digital trumps analog, there is still interest in poring over the physical and tactile details of streets and landmarks, either still around or long since plowed under, Jimmie and Marti say.

"Maps are hardwired into who and what we are," Jimmie said. "We are maps. We differentiate ourselves through language. What were the first things we discussed? Where we were. Where was danger. How we got there. How we got here. This is mapping. This is, in technical terms, the use of the hippocampus, the part of the brain that in fact is spatial memory and memory that allows us to recall both through the directional as well as the olfactory. All these tangential associations support mapping."

Jimmie grew up the son of academics. One brother, Richard, is chairman of the geography department at the University of Kentucky. His other brother, Chris, is a landscape architect in Baltimore. Jimmie is a proud, roll-up-your-sleeves autodidact.

"They did the hard grind of 10 or 15 years writing doctoral theses and all that," he said, smiling. "Me? I toured."

And he collected maps - mostly maps of California and the United States, though also of vast swaths of Europe, Asia, Africa, and even the polar regions. But it's San Francisco, Sacramento, and the Sierra regions that drive sales and engross Jimmie the most. He can deliver disquisitions on most of what's charted on the hundreds of maps filling cabinets, boxes, and shelves. Prices range from $5 to $50,000.

Marti has her favorites, too. One is by James Whistler - of Whistler's Mother artistic fame - a depiction of Anacapa, one of the Channel Islands in Southern California, for the government in 1854. Etched into the steel engraving was a tiny flight of birds. It turned out Whistler's employer wasn't thrilled with the artistic flourish and fired him, so Whistler fled to England and became established as an artist.

"I could just picture him saying to the government, 'You're stifling my creativity,' " Marti said.

The Scheins consider maps a legitimate art form. Jimmie, in fact, holds many so dear to his heart he sometimes has a hard time letting go.

"Now, he just hides some things away. But in the beginning, people would say, 'OK, I want to buy this,' and Jimmie'd say, 'Oh, yeah, that's not for sale,' " Marti said. "I'm taking him aside and going, 'I know it's hard, but you've got to part with it.' This is a business."

It is a business that survives, but for how long? Jimmie wistfully recalled the days when "in every city, there were two or three places like this" to scavenge for maps. He does not despair, though, when looking ahead.

"The youthful population is looking for the unique and the individualized in a mass-produced world of the trite and the digital," he said. "They use maps more than you and I ever did - on their phone. But that's ephemeral and not worthy of the paper you'd print it on. But I do find they're interested in conceptual mapping, geo-spatial mapping, or statistical overlays, like where the sewer lines run, or three-dimensional paradigms.

"Maps won't go away," he said, "they'll just change."