Khalil Wimes case shows gaps remain in child-welfare system

Six years ago, after it became tragically clear that children were dying under the city's care, Philadelphia officials promised to fix things - to do better at saving innocents.

Six years ago, after it became tragically clear that children were dying under the city's care, Philadelphia officials promised to fix things - to do better at saving innocents.

"Who is in charge who gives little children to people who are so obviously, absolutely, completely incapable of taking care of them?" one Common Pleas Court judge asked of Philadelphia's Department of Human Services.

A 2006 Inquirer investigation found that at least 20 children in two years had died of abuse or neglect after coming to the agency's attention.

Bosses were fired. Reports issued. A grand jury impaneled. Caseworkers remain in jail for skipping visits and forging paperwork while Danieal Kelly, 14, wasted away in a sweltering apartment.

Though changing the culture of an agency charged with protecting more than 22,000 imperiled children is no small challenge, child-welfare advocates agree that DHS has since shown marked improvement in leadership and organization, transparency, and ability to transform criticism into better practice.

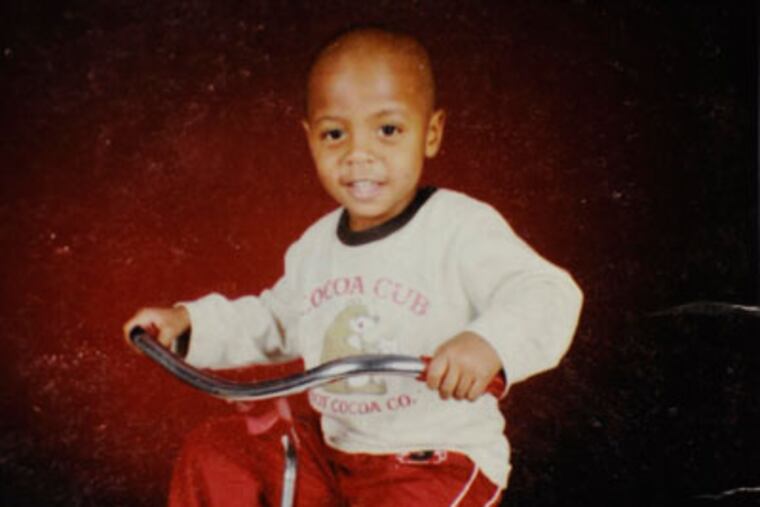

But last week, a state-mandated review detailed how Philadelphia child-welfare professionals failed at almost every juncture to rescue Khalil Wimes, a 6-year-old South Philadelphia boy the city removed from a loving foster home and returned to parents with a long history of neglect.

Those parents then starved and tortured Khalil, authorities say, while DHS failed to take any action. Khalil died March 19.

The detailed report faults decisions made by DHS staff and supervisors, a Family Court judge, city lawyers, and a primary-care physician. It makes plain that despite reform, Philadelphia's child-welfare safety net remains frayed in important ways.

A DHS social worker involved in the case has resigned. Khalil's parents, Tina Cuffie and Floyd Wimes, have been charged with murder.

DHS Commissioner Anne Marie Ambrose, who took over the troubled agency in 2008 and has been praised for her reform efforts, said last week that as heartbreaking as Khalil's killing was, it also presents an opportunity to prevent future deaths.

Ambrose said the agency has reinforced with frontline workers the requirement that family visits be documented within six days. Social worker Courtnei Nance failed to document her contact with Khalil until after his death.

"When these deaths occur, we look hard at what we did and didn't do," Ambrose said.

Below is an accounting - taken from the state-mandated review, DHS files, and court and police records - of the botched communication, poor judgments, blown opportunities, and shoddy casework that ended in Khalil's death.

Information gaps

Two days after Khalil was born on Valentine's Day 2006, DHS received a report that his parents were abusing drugs and keeping him in a decrepit rowhouse with no heat, hot water, or gas.

When a cousin of Wimes, Alicia Nixon, volunteered to take temporary custody of Khalil, the case was closed.

Under Nixon's care, Khalil thrived.

In February 2007, Wimes and Cuffie, who had 10 children, none of them in her care, tried to regain Khalil in Domestic Relations Court.

The judge, Robert J. Matthews, was operating with limited information. The thick DHS file detailing Wimes and Cuffie's calamitous parenting history never made it to court.

It would have shown that five of Khalil's older siblings had been removed. Plus, other children had aged out of the child welfare system. Eight abuse and neglect complaints had been lodged against the couple.

Information gaps frequently occur at this preliminary step in the Family Court process, said Frank Cervone, who runs the Support Center for Child Advocates.

No efficient pathway exists to share information between different branches of Family Court and DHS.

For example, the report points out, Domestic Relations Court and dependency court - which would have access to Wimes and Cuffie's history - lack computer compatibility.

"Custody Court is charged with making best-interest decisions for a child made with a whole picture of the child's life and well-being," Cervone said. "Far from having the whole picture, the court hardly had a snapshot of the present moment."

Matthews returned Khalil to his parents without the file, a decision the state report criticized.

"You have many cases a day," Matthews said Friday. "People come before you, present a brief story, and you must make the best decision on the information that's given you."

Concerned about the situation, he said, he made his order a temporary one, pending a review of the DHS file at the next scheduled court date.

"There is not one doubt in my mind that you absolutely love Khalil," Matthews told Nixon, at the end of the brief hearing. But "they are the mom and dad."

Five days later, Cuffie and Wimes took Khalil to an emergency room filthy, dehydrated, and suffering from an asthma attack.

Khalil was immediately returned to Nixon.

Bar set too low

For years, DHS demanded that Wimes and Cuffie find suitable housing and get sober. But the two ignored the agency's efforts, and in 2008 they permanently relinquished their parental rights to Khalil's five older siblings.

However, the law department left the window open on Khalil since Cuffie and Wimes had failed him for a shorter period of time. Khalil was almost 3 now, safe and healthy with Alicia Nixon.

DHS set several goals for Wimes and Cuffie: Undergo six months of drug treatment, find an apartment, get work. They also had to take a parenting class.

That bar was set far too low. The agency could have demanded more rigorous drug and mental-health screenings, Cervone said.

The state review noted the absence of a "parenting capacity evaluation," a psychological work-up assessing Cuffie and Wimes' caregiving ability.

The couple met their goals in 2008. DHS and the city law department withdrew their petition to terminate parental rights - over the objections of Khalil's DHS social worker at the time.

Judge Charles J. Cunningham returned Khalil to his parents in November 2008.

Richard Gelles, dean of the University of Pennsylvania School of Social Policy & Practice, said the city nonetheless had grounds to keep fighting for Khalil.

The Pennsylvania standard for terminating parenting rights: "clear and convincing evidence of parental inadequacy."

Gelles said, "The housing problems, the substance abuse, the voluntary giving up of parental rights: They had conceded their inadequacies with their other children."

The report also criticized the law department, noting that a supervisor may not have signed off on Khalil's return.

It recommended that a directive be reissued that all solicitors must fully prepare cases presented in court. "Every solicitor should be familiar with the history of the case," the report said, "including the circumstances that brought the family to the attention of DHS."

Ambrose said the law department has reissued that directive. Barbara A. Ash, chief deputy city solicitor of the Child Welfare Unit, declined to comment.

The unwillingness to pursue termination in all but the surest cases has become a pattern, Gelles said. The cases are difficult, uncertain, and time-consuming.

Taking five children from troubled parents while giving one back, he said, made no sense.

"If the best predictor of human behavior is what you have done in the past, why would you give them the youngest child? Why plea-bargain him away?"

'Failure to thrive'

DHS monitored Khalil for one year after he was returned to his parents - the longest period the Philadelphia system allows.

During this time, when Khalil was 3, Cuffie took him to see Dr. Carl Liedman. At 36 pounds, Khalil's weight and height appeared normal.

In January 2011, after the monitoring stopped, Liedman saw Khalil a second time - the final time the boy would receive medical care before his death 13 months later.

Now nearly 5, Khalil had lost two pounds and had fallen off the height chart.

"All is well," Liedman wrote in his files.

The state review team - which consists of Philadelphia doctors, police, prosecutors and DHS officials, including Ambrose - directed the filing of a negligence complaint with the Pennsylvania Board of Medicine against Liedman. The doctor did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

If no medical explanations are found for a child's "failure to thrive," doctors, mandatory reporters in Pennsylvania, must contact child-protection services.

DHS's last chance

Even after a judge decided without full knowledge of the case, even after the city returned Khalil to danger, and even after a doctor failed to notice the child's failing health - DHS still had a chance to save him.

DHS reentered his life for the last time in the summer of 2011, when prosecutors and Khalil's relatives say he was suffering regular beatings and sleeping on a small, soiled plastic mattress in a latched bedroom with no other furniture. His parents were slowly starving him.

That summer, a DHS social-work team facilitated visits between Khalil and his siblings. The eight visits took place at Cuffie and Wimes' apartment and at a DHS "Achieving Reunification Center."

Though not specifically assigned to Khalil, the DHS social worker, Nance, supervised the gatherings and saw him at his home two weeks before he was killed.

She did question Cuffie about the boy's weight and facial bruises, but accepted her explanations that he had a stomach disorder and bruised easily because of a skin problem.

Focusing solely on the shoddy casework does not address larger systemic issues, Gelles said. Supervisors need more training, and despite all the reform, the agency's system for evaluating risk still needs improvement.

The agency must develop a more scientific way of assessing the danger of children under its care, he said.

Too often now, it relies solely on the judgments of social workers - an assessment, he said, "no more accurate than flipping a coin."

And while Ambrose and her leadership team have made the safety of children the paramount concern of their reform, he said, the understanding of that mission can become clouded when it trickles down to frontline workers.

"They have lots of procedures in their manual, but they don't know why they're going into a house: to help a parent or protect a child," he said. "You're supposed to be going into the house because you're in the business of ensuring the safety of every minor child in that house. We haven't achieved that yet in Philadelphia."