Gettysburg reenactment is a campaign in itself

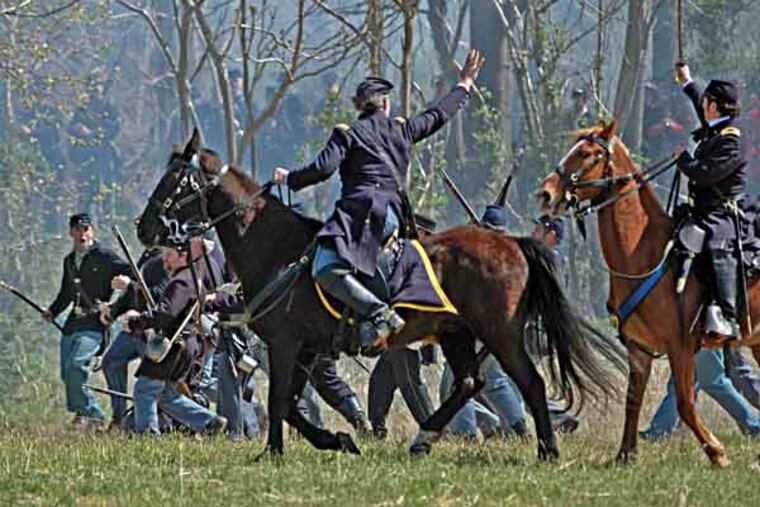

The armies are already beginning to arrive, days ahead of the big battle. Tucked away in the rolling Adams County countryside are rows of billowy white tents. Men in blue and in gray march with shouldered muskets. Officers on horseback ride by with sabers jingling at their sides.

The armies are already beginning to arrive, days ahead of the big battle.

Tucked away in the rolling Adams County countryside are rows of billowy white tents. Men in blue and in gray march with shouldered muskets. Officers on horseback ride by with sabers jingling at their sides.

One hundred and fifty years after the bloodiest clash ever fought on the continent, Union and Confederate forces are again gathering like storm clouds around tiny Gettysburg, this time for a bloodless re-creation of the epic battle fought there.

Beginning Thursday and continuing through next Sunday, scores of cannons will roar, the ground will shake beneath the feet of hundreds of horses, and long lines of federal troops will fire volleys, like sheets of flame, into the oncoming rebel soldiers.

"It's extremely accurate and feels real - the noise, conditions, and spectacle - but you're not confronting the likelihood of you or your friends being killed," said Jon Sirlin, a Philadelphia lawyer who portays a Union officer and chief of staff, one of an expected 15,000 reenactors.

The event - put on by the Gettysburg Anniversary Committee at a cost of about $1 million - will cover the major engagements of the battle, which raged July 1-3, 1863.

Another smaller battle reenactment held by the Blue Gray Alliance is underway through today at the Bushey Farm on Pumping Station Road.

"I think of it as a historical Woodstock," said Randy Phiel, one of the organizers of the larger July 4-7 event, which is expected to draw up to 80,000 spectators on the two farms outside Gettysburg.

The challenges of overseeing such large crowds and so many reenactors on two sprawling farms will be daunting.

"We train in individual units of maybe 30, 40, or 50 guys," said Sirlin, 64, of Center City. "Then, we get together with a unit of 100, and a larger unit of 500.

"But nobody gets together with 10,000 guys," he said. "We really do give orders on the field and have to follow a plan."

Those plans, as in 1863, are known only to the officers. "You have to respond to what happens," Sirlin said. "Mistakes happen, just like they do during the real thing. . . . You get a better feeling for how things go wrong."

The spirit of the Southern army was running high in the spring of 1863. The Confederates under Gen. Robert E. Lee had just won a stunning victory at the Battle of Chancellorsville in Virginia, and they began the invasion of the North on June 3, 1863.

Long columns of ragged, dirty troops, many without shoes, snaked through the Shenandoah Valley and crossed the Potomac into Maryland, on the way to Pennsylvania.

Their steady progress was alarming to residents across the commonwealth. Gov. Andrew Curtin called out the militia June 12 and asked New York to help repel the rebels.

Residents of York, Carlisle, Chambersburg, Lancaster, and Harrisburg hid their belongings, others fled, and some Harrisburg citizens drilled in the streets with brooms and boards for lack of weapons.

The Confederates were not expecting a friendly welcome as they marched into Pennsylvania. On Northern ground, they knew they would have a tough fight with thousands of casualties.

"Do I have enough supplies to sustain the amount of injuries we're liable to have?" asked Harry Sonntag, who portrays the commander of a Confederate field hospital. "The answer to that is always no, especially on the Confederate side."

"Do we have enough shelter?" he asked. "How do I make this work?"

Sonntag, 46, of Phildelphia's Winchester Park section, had an ancestor, Peter Kelly, who served with the 98th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment at Gettysburg. Kelly's name is on a plaque on the Pennsylvania Monument.

"I don't know why I chose the Confederates," said Sonntag, who described the challenges faced by Southerners. "The surgeons sometimes had to acquire what they needed from [captured] Union surgical kits and make do with less."

Sonntag, who portrays a Southern doctor, Hunter McGuire, works as a medical consultant and is vice president of the American Living History Education Society.

"I've always had a fondness for medicine," he said. "My mother's family wasn't far from Gettysburg, and my dad used to take me there."

Until 1863, the Civil War had been fought largely in the South, much of it in Virginia. As he led his 70,000-man Army of Northern Virginia into Pennsylvania, Gen. Lee hoped to give his home state time to recuperate.

"The question of food for this army gives me more trouble and uneasiness than anything else," said Lee, according to historical accounts. The rich farmlands of Pennsylvania would keep the troops supplied.

Southern leaders also hoped the invasion would create opportunities to threaten Baltimore, Washington, Philadelphia, and Harrisburg.

Lee crossed the Maryland-Pennsylvania border in late June without his "eyes" - Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart. Stuart's cavalry usually kept Lee apprised of the Union Army's position, but he was off to the east, effectively out of the campaign.

But that did not discourage the ever-aggressive Lee, who told one of his generals that if Harrisburg "comes within your means, capture it!"

Many Northerners were frustrated by their military's lack of success on the battlefield.

The coming fight "is key," said Jon Sirlin, who has participated in many reenactments, assuming the persona of a Union officer and often directing troops from horseback. "These guys defeated us badly at Chancellorsville and Fredericksburg, and it seemed they were better than us.

"But think of what Lee has said - that the South doesn't realize how much more powerful the North really is, and ultimately that the South will lose," he said. "We should be winning this war."

Most of the time, Sirlin has both feet planted in the 21th century as a civil litigator specializing in business, real estate, and creditor's rights.

But at Gettysburg, he has entered a time when soldiers salute and address him as "sir." He's an officer in the Union army, and it's do-or-die time for the Northern cause. He dons a wool uniform and heavy leather boots - everything necessary to experience the soldier's life.

And when there are no cars, planes overhead, or utility poles in view, he can easily imagine the past - what reenactors call "magic moments."

"I've had a number of them," Sirlin said. "You feel immersed in the time. "My horse and I are one creature," he said. I feel everything is real, and happening in front of me."

The Confederates were moving quickly. One rebel recalled "breakfast in Virginia, whiskey in Maryland, and supper in Pennsylvania" all within a day.

The army entered Chambersburg on June 24, Gettysburg on the 26th, and York, Wrightsville, and Carlisle on the 27th and was four miles outside Harrisburg on the 28th.

On the way to Gettysburg, one Southern soldier noticed the road under his feet covered with playing cards, apparently discarded by repentant comrades. They knew they were facing death.

On June 28, Henry Jacobs took his telescope to the Lutheran Theological Seminary on Seminary Hill, west of Gettysburg, to watch the armies. In the distance, he saw the rebel camps. "Wherever the mountainsides held clearings, smoke curled upward," he said.

Capturing the dramatic look of the coming battle was the job of artists such as Alfred Waud in 1863 - and Terry Jones 150 years later.

Jones, the sculptor of the Gen. John Gibbon bronze statue on the battlefield, will portray an artist of the time. He is outfitted for the role with high cavalry boots, a duster, slouch hat, Navy Colt sidearm, and sketch pad.

"I'm a combat artist, and there's going to be combat," Jones said as he sank into his role. "I'm going to try to position myself" to see the battle.

The Newtown Square man will spend his time in the Union camp, trying to capture the feeling of the event much as Waud did.

"The artists then had a certain panache and flamboyance," said Jones, 66. They "tried to get close to the engagement.

"They'd sketch the broad outlines of what they saw," he said, "take notes in the margin, then finish later."

By June 29, a force of 90,000 Union troops - the Army of the Potomac - was deployed along a 20-mile front, from Emmitsburg, Md., near the Pennsylvania border, to Westminster, Md.

At about 11 a.m. the following day, federal Brig. Gen. John Buford's cavalry entered Gettysburg, minutes after the withdrawal of a brigade of Confederates looking for shoes.

Confederate Brig. Gen. James Johnston Pettigrew watched them through his field glasses from a nearby ridge. He didn't count on this.

In Gettysburg, residents were frightened. "Found everybody in a terrible state of excitement on account of the enemy's advance," Buford reported.

Fifteen-year-old Tillie Pierce said: "I had never seen so many soldiers at one time. . . . I then knew we had protection, and I felt they were our dearest friends."

For Sonntag, those moments when the present slips away - and the past takes over - often come at the end of the day.

"The camp is set up, the sun is going down, the lanterns are being lit, and the campfires are going," said the Confederate reenactor.

"I'm sitting in the tent and people are coming in," he said. "I'm on the same ground, hearing the same reports."

That's when Sonntag can easily forget he's living in 2013. "I can only imagine that this is the way it must have been," he said. "You don't remember you're Harry Sonntag. . . . It's an interesting feeling."

As Union troops settled in for the night west of the seminary along McPherson Ridge, Brig. Gen. Buford and his commanders assessed their chances for the following day.

The bulk of the army was still miles away. All that stood between the rebel army and the good defensive ground he was holding were a few thousand troops.

The same night, Lydia Catherine Ziegler, a young girl living at the seminary, looked out from its cupola over the campfires of the armies and felt a sense of sadness:

"Many of the soldiers were engaged in letter writing, perhaps writing the last loving missives their hands would ever pen to dear ones at home."