Owners pressed for faster demolition before fatal collapse

The message came through loud and clear: The buildings in the 2100 block of Market Street needed to come down, and their chief owner was growing impatient. He'd stopped by in late April and was "shocked" to see them still standing.

The message came through loud and clear: The buildings in the 2100 block of Market Street needed to come down, and their chief owner was growing impatient. He'd stopped by in late April and was "shocked" to see them still standing.

The aide who passed that news along put shocked in capital letters.

A new cache of e-mails tied to the Center City building collapse sheds light on one of the basic questions about the deadly June accident: why the owners pressed forward with plans to tear down a four-story brick building amid serious safety concerns about the one-story Salvation Army thrift shop next door.

The e-mails exchanged by representatives of STB Investments Corp. offer clues to their thinking even as they were warning the city and the Salvation Army of the perils the demolition posed to the thrift shop and to its occupants.

The e-mails are among many documents turned over to Philadelphia prosecutors as part of an ongoing grand jury investigation into the collapse.

Here are some of the clues contained in those e-mails, copies of which The Inquirer obtained:

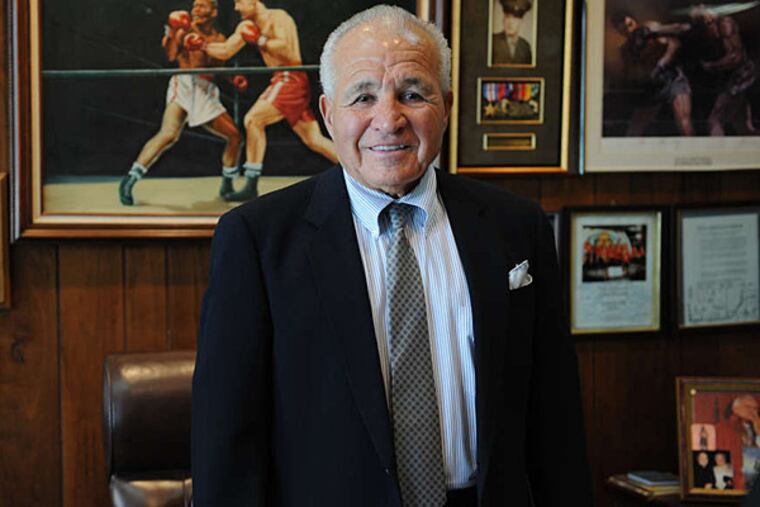

Richard Basciano, the 87-year-old real estate investor who is the principal owner of STB of New York City, wanted things to move faster at the site - and he visited in person to check up on it.

"Richard and his wife passed by . . . yesterday. He is SHOCKED that this project is not done," Thomas J. Simmonds Jr., property manager for Basciano, wrote on April 29 to Plato Marinakos Jr., the local architect who acted as STB's liaison to the demolition contractor.

Marinakos had said the demolition work would be finished by the end of April. Now he told Simmonds it would be done by the first week of May. But the building at 2136-38 Market was still standing on May 31 when Basciano, according to other e-mails, checked again.

"Richard is on the phone now; he passed by the job site and observed no one working," Simmonds wrote to Marinakos and others on May 31. "Please advise - he will be visiting the site over the weekend."

Another e-mail reported that Basciano did visit the site that weekend, on Sunday, June 2. That time, "Richard and his wife stopped by and seemed please[d]," Marinakos reported to Simmonds. "I am glad he saw more progress today."

That same weekend, without notice to the Salvation Army, the demolition contractor had brought in an 18-ton motorized excavator - "that yellow machine," a thrift shop employee later called it. "If they had told us they were going to rip the building down with a machine like that, the Salvation Army would have done something," the charity's lawyer, Eric A. Weiss, has said.

Caught between a demanding owner and the pace of the demolition project, Basciano's New York property manager, Simmonds, fumed at delays in negotiations over safety plans by "these people and their half-baked charity" - the Salvation Army - at a time when "I have to look after the interests of the Owners."

Thomas A. Sprague, one of the attorneys representing Basciano and STB, declined to comment on the new set of e-mails. Simmonds and others who sent or received the e-mails declined to comment directly or through their lawyers.

The e-mails are now part of the evidence that led to this finding in the grand jury's presentment, released Nov. 27:

"E-mails and testimonial evidence reveal that by the end of May 2013, Basciano and STB staff were aggressively pushing for demolition progress on the 2136-38 Market St. building."

The presentment went on to cite testimony Marinakos gave after being granted immunity from prosecution. The architect told grand jurors of a June 4 meeting with the demolition contractor, Griffin Campbell, who faces criminal charges in the collapse.

Campbell had incentives of his own for speeding the project along. He had a $112,000 contract with STB to demolish three buildings on that block of Market, where Basciano wanted to build an upscale residential development, a gateway to Center City. Campbell had already torn down the two smaller structures, collecting $71,000, and hoped for another progress payment.

Marinakos said Campbell telephoned him the day before the collapse.

"Griffin called me and said . . . he wanted to put in an application for payment and he wanted me to take some progress photographs and show how the progress is going, to kind of alleviate the push from the owner to get it done," the architect testified.

Marinakos said he went to the site about 6 p.m. June 4, and was alarmed to see the brick wall looming next to the Salvation Army building.

By then, most of the wooden joists, flooring, and support beams had been removed, according to the presentment. The grand jury said Campbell was reselling the joists for $6 and $8 each.

Marinakos testified he urged Campbell to take the wall down immediately: "I was like, 'Griffin, you can't leave this wall here. This is just crazy. I mean, you can't do that.' "

After that, the grand jury presentment said, Campbell sent two workers up to take the wall down. But they had made little progress by the next morning.

A slow negotiation

A factor that has surfaced again and again in the aftermath of the fatal collapse is the drawn-out negotiations that took place between STB's representatives and the Salvation Army. The building owners wanted Campbell's demolition workers to get access to the thrift shop roof so they could knock down the adjacent brick wall; the charity wanted assurances no harm would come to its shop.

The Basciano group had contacted the Salvation Army in February about the demolition plans. But three months and many e-mails later, little had been resolved, and the demolition of the four-story brick building next to the one-story thrift shop was underway.

On May 22, Alex Wolfington, a real estate marketing consultant on the Basciano team, e-mailed Simmonds to suggest having another conversation with a Salvation Army executive about getting access to the shop roof.

That prompted Simmonds to vent his frustration.

"Why?" he replied. "Waste more time? Wait for someone to be killed? You can do what you want but I am NOT backing off with these people and their half-baked charity. Perhaps you have the time and/or desire to 'deal' with their idiotic behavior: I don't and I won't. I have to look after the interests of the Owners - Richard and his daughters."

It was the second time that day a Simmonds e-mail had noted the danger. That afternoon, he had reached out to city Commerce Director Alan Greenberger, asking if the official could intervene with the Salvation Army.

In that e-mail, disclosed by The Inquirer in July, Simmonds told Greenberger: "This nonsense must end before someone is seriously injured or worse: those are headlines none of us want to see or read."

Greenberger, whose additional duties as deputy mayor for economic development included overseeing the city's Department of Licenses and Inspections, has since acknowledged he did not alert city inspectors to the dispute.

He has said he believed STB and the Salvation Army were "working together to resolve the outstanding issues" by then. He cited an e-mail he received from Wolfington, sent less than an hour after Simmonds' message, saying the marketing consultant intended to meet with the Salvation Army on measures to protect the thrift shop building.

In the end, the Basciano group and the Salvation Army never reached a final agreement. Campbell's demolition crew had already stripped the brick wall of most of its support timbers and flooring. On June 5, the wall collapsed, crushing the thrift shop with 19 people inside. Six of them died.

The e-mails The Inquirer reviewed do not fully explain Basciano's interest in completing the project quickly. But there may be another clue in an April 23 e-mail from Marinakos to Simmonds, stating - incorrectly, as it turned out - that a high-reach boom was being brought in to enable workers to disassemble the building from the top down.

In that e-mail, Marinakos told Simmonds: "They are taking the floors out board by board to reinstall in another building. This takes more time. By the end of the month, all the buildings will be gone."

Basciano had planned to pave over the site and use it for surface parking while he prepared the block for redevelopment.

"We should be ready for asphalt soon after," Marinakos added in the April 23 e-mail. "I am getting prices for that."

215-854-5885