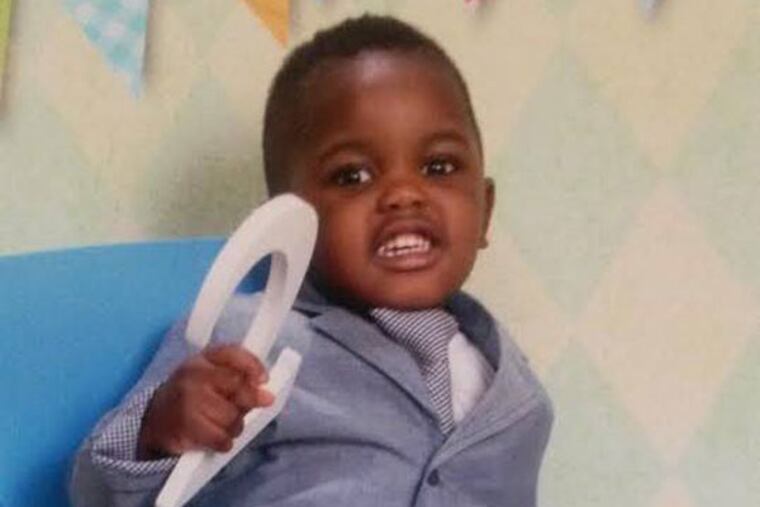

The sad, short life of Sebastian

Here is the sad, short story of the life of Sebastian. And the story of the agency charged with protecting him.

Here is the sad, short story of the life of Sebastian. And the story of the agency charged with protecting him.

Sebastian's story is heartbreaking. The other story is proof that while Philadelphia has come a long way in protecting endangered children, there is still a good way to go.

Sebastian Wallace died of an overdose in October. He was 2. He had enough of his father's illegally obtained Oxycodone pills in him to kill an adult three times over.

Police in Bucks County - where Sebastian was staying with his father - have not said exactly how Sebastian ingested the pills. But the father has been charged with homicide and child endangerment.

Meanwhile, a death review report released by the Philadelphia Department of Human Services last week shows there were warning signs in the first year-and-a-half of Sebastian's life, when he lived in Philadelphia with his mother and siblings, before he ever wound up with his father and his pills.

Between 2011 and 2013, the agency received six complaints about Sebastian's mother - some made before he was even born.

The allegations are hard to stomach. The house was filthy and the kids were eating carrots off the floor. The mother was selling her food stamps. While the kids slept on the floor, their mother used the bedroom for prostitution.

When Sebastian was 5 months old, the agency received another report: The younger children could be heard crying all day. The older ones were not attending school. The mother beat one of the children with a pipe.

In all but one of the six cases, social workers who investigated the complaints returned with reports that read "no findings present" or "unfounded."

There's no disputing that this was a child in a drowning family that needed help. But as much as cases like this demand outrage, they also deserve context.

Ask city child advocates about DHS, and they will tell you it is a vastly better agency today than it was 10 years ago. That it no longer buries its mistakes, but learns from them. That under the previous leadership of Commissioner Anne Marie Ambrose - and continuing with Commissioner Vanessa Garrett Harley - the agency has committed itself to reform.

But it's like turning an ocean tanker around. It takes time.

The report on Sebastian's death is proof itself of the agency's commitment to openness. Since 2009, a team of child-welfare advocates, chaired by Medical Examiner Sam Gulino, has reviewed every child-abuse fatality in the city.

These are not DHS apologists. They are doctors, law enforcement officials, social workers, and school officials. Their conversations are frank. They demand answers and issue careful recommendations - and expect them to be followed.

The heart of a problem

But that is what's most concerning about the report on Sebastian's death. After hearing about all those earlier complaints, the review team called on the agency to set up a system to flag families with a high number of abuse or neglect reports, even unfounded ones. A sort of sound-the-alarm mechanism.

That's great. But, according to the reports, it's a recommendation the team first made in 2009 - and has made twice since.

It's a recommendation at the heart of a problem still plaguing DHS: children who died or were seriously hurt after the agency had received many warnings that they could be in danger.

That raises concerns about whether, despite all the challenges, DHS is acting quickly enough to solve key and potentially life-threatening problems.

Taking action

It's the same issue found in another report the agency released this month, about a Frankford infant who nearly drowned in the bathtub. Like Sebastian's family, this family had six earlier complaints. As it did in Sebastian's case, the review board called on DHS to reexamine its handling of these high-activity cases, no matter when the complaints were made.

DHS has taken some action. In 2014 - five years after the initial recommendation - it began reviews of families with four complaints in six months.

Tuesday, the agency's spokeswoman, Alicia Taylor, told me that given the latest recommendations, DHS is considering extending that from six months to a year.

That would be a good step. It wouldn't have helped Sebastian.

215-854-2759 @MikeNewall