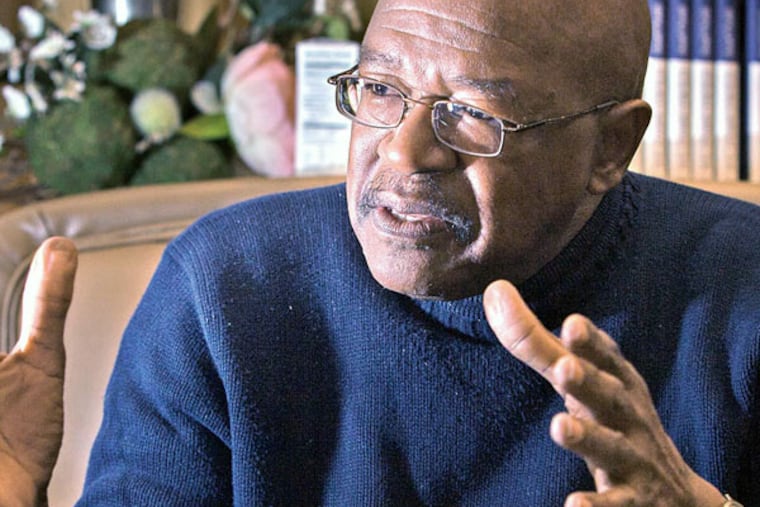

The Interview: Elijah Anderson

ELIJAH ANDERSON, one of the country's leading authorities on race and race relations, spent 32 years teaching at the University of Pennsylvania before he became a professor at Yale University in 2007.

ELIJAH ANDERSON, one of the country's leading authorities on race and race relations, spent 32 years teaching at the University of Pennsylvania before he became a professor at Yale University in 2007.

But Anderson still uses Philadelphia as a research site. Many of the examples in his latest book, The Cosmopolitan Canopy, which was published in 2011, and in his most recent article, "The White Space," which was published this year in the journal Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, come from Philadelphia. The book's cover is a photo from Reading Terminal Market.

The "white spaces" in society, in Anderson's classification, are places where there is a clear absence of black people, and black people in those white spaces can often feel disadvantaged or profiled. The "cosmopolitan canopies" are the spaces where people of all ethnicities come together to observe each other and interact.

Anderson, who was recently in town to speak about his work as an urban ethnographer, talked with Stephanie Farr about white spaces, black spaces and everything in between.

Q Is there a defining event in your youth that pushed you into urban ethnography?

I canvassed the businesses in South Bend, [Indiana], when I was 11. I came across Mr. Forbes at this typewriter store. [He gave me] a job. I had a payday.

I learned about him, I learned about the world. All these customers would come in, and his friends would come in. So that was very important, and being black and in this kind of white world was a whole new thing for me.

You see this whole view of the world that you otherwise wouldn't get. And that made me very curious, I think, about different kinds of people and the situations in which they lived.

To [Mr. Forbes], I was Elijah but I was a colored boy, and he would talk about the colored boys and the colored people and the white people sometimes. He would reach out to colored people, but he still had this distinction. But certainly, I could feel love from him. So that was one of my most critical early experiences with race.

Q Would you say that black people often find themselves in white spaces but white people don't typically find themselves in black spaces?

Within the structure of our society, white people typically avoid black space but black people have to navigate the white space as a condition of their existence because that's where the goodies are: education, jobs, opportunities, a night out on the town and the promise of acceptance.

Q Do you think it would benefit white people to find themselves in a black space?

Sure. People might become brilliant in terms of understanding what's going on. Without broad experience people can be incapacitated, or at least not have the ability to see another person as a human being. So you would hope that through experience we could then hope for a better world.

Q Is the cosmopolitan canopy a good thing because it brings people together or does it only serve to highlight the segregation outside the canopy?

I think it's a good thing because not only is it this island of civility but it exists in a sea of segregated living. And it's diverse. In a sense, just to have the experience of the canopy is to become relatively sophisticated.

You can come from the most ethnocentric, parochial background and you come to Rittenhouse Square and spend some time there, you see men kissing each other, a black woman and a white man together, you see Jewish people and Muslims getting along.

So they model, and you could be coming out of cornfields and you become relatively more sophisticated.

The canopy is an edifying institution, it edifies, it teaches, it shows, it models. That can apply to different places, even a Starbucks.

Q What do you think of the Race Together campaign by Starbucks that called for its baristas to engage customers in conversations about race?

They already do it, but they do it at Whole Foods, too. I speak about this in the canopy book. I mention Whole Foods, I mention Starbucks. There are conversations that are going on that are silent. People note this person over there, note that person over there and they return. And they like it.

There's a sense in which you almost need a dose of the diversity of the Reading Terminal Market, of Rittenhouse Square. What that encourages is a feeling of belonging. There are all different kinds of people - and I'm here, too. That's the beauty of the canopy.

But there are fault lines. Once in a while a fault line will erupt, and people can become insulted in a profound way. Then the canopy recovers, we learn important lessons about one another and we move forward.

Q Do you ever find that your work makes people uncomfortable?

Sure. I'm not trying to. I'm just trying to represent what I see.

Q Do people still have a hard time talking about race?

Some people do and they can be mentally and socially stretched by such work, and maybe that's a good thing.