City identifies cops from controversial shooting

A trove of records released yesterday shed more light on the fatal shooting of Brandon Tate-Brown.

SO WHAT really happened on the night a Philadelphia police officer fatally shot Brandon Tate-Brown?

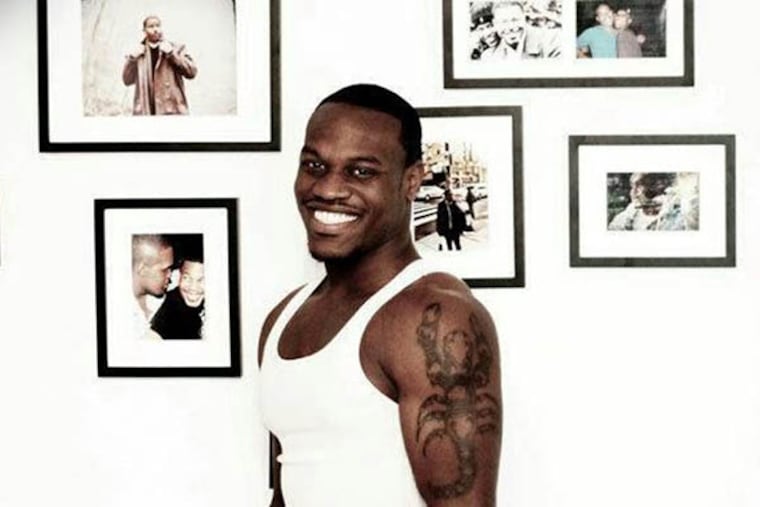

That's the question Tate-Brown's family and their supporters haven't stopped asking since the 26-year-old was gunned down in December after struggling with two patrol cops who pulled him over in Mayfair.

Yesterday, the city released a plethora of files - interview transcripts, videos and DNA evidence - and even identified the cops who were involved in the controversial incident.

The information sheds new light on the case. But contradictions in the basic narrative still linger, meaning the Tate-Brown family's burning question will probably never be resolved to everyone's satisfaction.

Officers Nicholas Carrelli and Heng Dang - rookies with about 19 months each on the job at the time - told investigators that they stopped Tate-Brown on Dec. 15, on Frankford Avenue near Magee, because he was driving his borrowed Dodge Charger with just its daytime running lights. A struggle soon erupted, and Carrelli, who later told investigators he spotted the butt of a gun in Tate-Brown's center console, shot Tate-Brown once in the head.

Dang told investigators that Carrelli had a Taser, but Carrelli said he "never had an opportunity to use it because we were involved in a hand-to-hand struggle."

The city gave the documents and several surveillance videos to attorney Brian Mildenberg, who represents Tate-Brown's mother Tanya Brown-Dickerson, as part of a wrongful death and excessive force class-action lawsuit she filed in April against the city. Mildenberg had filed a motion to compel the information as part of his lawsuit.

The Nutter administration dumped the documents in a Dropbox for the public to access, and sent out a press release touting their release as being "In accordance with the City of Philadelphia's ongoing efforts for transparency in governance."

But the documents were due tomorrow, Mildenberg said.

John McNesby, president of the Fraternal Order of Police Lodge No. 5, said the union wasn't told ahead of time that the officers' names would be made public.

Tate-Brown's family and protestors who brought national attention to the case repeatedly called for the officers to be identified, but the city resisted for months.

"The names of the officers were only not given earlier because of threats that were made, which we continue to be concerned about," said Police Commissioner Charles Ramsey.

District Attorney Seth Williams cleared the officers of wrongdoing, saying Tate-Brown reached inside the car for a gun after breaking away from the officers during a brief but violent scuffle.

Mildenberg singled out that rationale as the biggest discrepancy in the case.

The Police Department has maintained that Tate-Brown was shot as he reached into the passenger side of his car, possibly trying to retrieve a stolen, loaded, hidden handgun Carrelli had spotted earlier jammed into the center console. But in his statement to Internal Affairs, Carrelli said he opened fire when Tate-Brown "ran around the trunk of the Charger, " according to the interview transcripts.

"To me, the big story is that the whole story about him reaching into the car was a lie," Mildenberg said. "That is not true now, and it's never been true."

Other discrepancies are still unexplained.

A witness who approached the cops after the shooting said one officer told him Tate-Brown was stopped for driving "a vehicle that was described in a robbery earlier."

But Dang told Internal Affairs investigators that he pulled over Tate-Brown because he drove with just his daytime running lights on. "I figured he just came out of a store or something and we just [were] going to check to see if he was OK to drive and tell him to turn his lights on," the transcripts show.

Brown-Dickerson didn't know about the newly released records until the Daily News reached her yesterday afternoon. But she celebrated their release, saying transparency was key in settling the disputed details of her son's death.

Brown-Dickerson's lawsuit calls on the court to require 91 recommendations for reform that the federal Justice Department made in a May report on Philadelphia's police-involved shootings, which have averaged nearly one per week since 2007.

"If they would just follow them, not just Brandon but a lot of people wouldn't be dead right now," she said.

Dang and Carrelli told investigators that Tate-Brown repeatedly refused their commands, had an unknown object in his hand, later determined to be a cellphone, and appeared to fumble with his waistband as he tried to dive into his car. "If the officer didn't shoot him, the guy was definitely getting in the car," a witness told police.

Tate-Brown's relatives, meanwhile, have argued that police stopped Tate-Brown for "driving while black" in a mostly white neighborhood.

Blog: phillyconfidential.com