Elegy for the City Paper

I was 24 years old, tending bar back home in Brooklyn, and taking grad courses in literature at Brooklyn College. Mostly, I was writing bad poetry on bar napkins.

I was 24 years old, tending bar back home in Brooklyn, and taking grad courses in literature at Brooklyn College. Mostly, I was writing bad poetry on bar napkins.

The last few years had been filled with loss - for me, for the city, for everybody.

First, my older brother John, who had been battling an addiction - a disease - he could not beat, sat down against a fence by a vacant lot one afternoon in 1999 and died. He was feet from a bus stop. The bus went by twice before anyone stopped to help.

My brother was handsome as hell with a killer smile and laugh, a talented guitarist and songwriter, a kindhearted listener, the person I looked up to. He just couldn't work it out.

Then, the planes hit the towers, and everything changed for everyone.

In the neighborhoods where I grew up - Marine Park in Brooklyn, Breezy Point in Queens - so many had followed their fathers into the Fire Department. Others took a different path, to careers in finance, at places like Cantor Fitzgerald.

The funerals stretched on for months. After some, we would go to the Harbor Light, a Rockaway pub owned by the Heerans.

Charlie Heeran's father is a retired firefighter. Charlie, a high school friend, worked for Cantor Fitzgerald. We went there after Charlie's funeral, and, again, two months after the attacks, in a daze of shock and grief, when American Airlines Flight 587 fell from the sky and onto neighborhood homes, killing another one of the best of us, Chris Lawler, and his mother, Kathleen.

One morning soon after, I was working at my bar, when I saw an article in the Times about the Harbor Light and the Heerans and the Lawlers and Rockaway. The author had spent only a few hours in the neighborhood, but the article read as if he had known the good people there for years.

He had captured the place and the people and the emotions with honesty and dignity. He had made their voices permanent. And at the time, just as it does now, that seemed like the most important thing I could try to do to work it out.

I chose to do it in Philadelphia partly for a girl, and partly because writing about another city was easier than facing my own. And partly because I was still young enough to believe that a new city could erase any amount of pain or grief.

I had been here a few weeks when I saw a yellow banner hanging from an office balcony on Walnut Street. "Philadelphia Weekly," it read.

I applied for an internship, and landed it. An editor later told me I was hired because I had worked at a Bruce Springsteen fan magazine after college. That carried weight.

I knew nothing about newspaper writing. My first assignment was 400 words on a possible janitorial strike at Penn. I turned in a story that opened with a long quote from John Steinbeck's 1936 novel about a fruit picker's strike, In Dubious Battle.

Needless to say, that story made it into print only after heavy editing, but they let me keep working it out.

They told me to show up two days a week. I went five. At some point, I dropped the Steinbeck quotes, and I guess they felt they had to start paying me.

It was the mid-2000s, and it was a marvelous time to work at an alternative weekly. And with both Philadelphia Weekly and the vaunted City Paper still healthy, if not thriving, it was an incestuous time, with staffers bouncing back and forth between the two.

I was one of them and was at the City Paper in two years. It was a place, like the Weekly, where they hired you not for what you had done, but what they thought you could do.

It was a path to journalism for misfits, musicians, bartenders, and bad poets. And it worked. Some of the brightest talent in Philly and in national journalism came up through our weeklies. It was a Murderers' Row of talent, and we were all figuring it out as we went along.

At the City Paper, with its worn, sprawling offices at Second and Chestnut Streets, in the old Corn Exchange building, we were given the keys to a city, to write whatever we wanted. The only criteria for a story were that it interested you, and might interest others. And in that way, an ever-evolving narrative of the city emerged. It was hard-hitting, feet-to-the-fire journalism, and God, was it fun.

And the space they gave us to write! Thousands and thousands of words, enough to get all your good words out and the bad ones too, and that, for a young writer, is just as important.

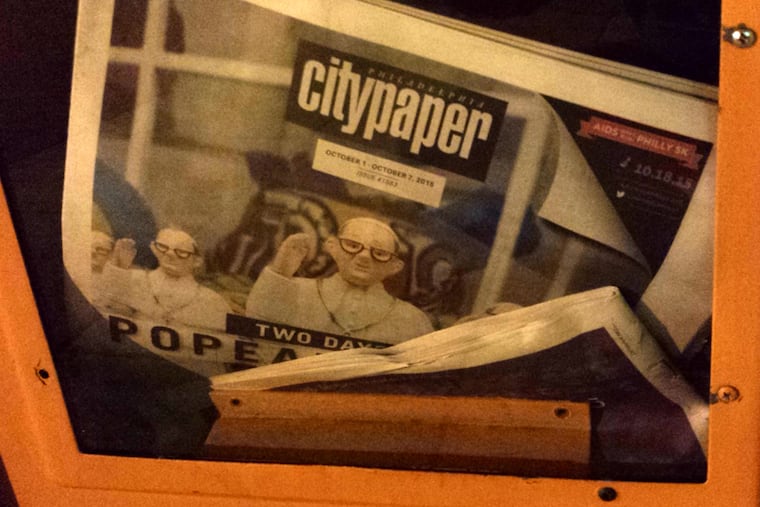

On Wednesday, the parent company of Philadelphia Weekly announced that it had purchased City Paper, and would publish its last issue this week. The Weekly, soon the only alt-weekly left in this city, is itself hanging on by a thread, running full-page ads for e-cigarettes on its front page.

The news hit hard. The scoundrels notified the CP staff that they were getting laid off through a press release. They deserved so much better. And the staff was told that the paper's extensive online archive may disappear, too. What a loss.

In my time at City Paper, I cleaned my office out twice, sure they would fire me for blowing deadlines. But they kept letting me work it out, as they had for so many others before and after me.

And I did. In documenting other people's lives, in making their voices permanent - their grief and their struggles and their happiness, too - I was able to start working through my own. I will always be grateful to the weeklies for that.

And the city should be grateful for a place that gave so many young writers a chance to write their stories and others'. To keep at it. To keep working it out.

215-854-2759

@MikeNewall