Captain Noah sings us a rainbow

At 89, Carter Merbreier of Captain Noah fame would still like us to say our prayers.

TWENTY-ONE YEARS after he left the high seas of local television, Captain Noah is thinking about his final voyage.

"At my age, you know you're closer to death than when you were 49," says the 89-year-old captain, a.k.a. W. Carter Merbreier, star of Captain Noah and His Magical Ark, the iconic kids' show that ran on WPVI-TV from 1967 to 1994.

"And please don't say, 'Oh, but even a 49-year-old could get hit by a truck!' as though the odds of dying soon are equal for everyone. At 89, my odds are greater."

When he eventually goes, obituary writers "might want to write about my passing," Merbreier says modestly.

How could they not?

At its peak, Captain Noah was syndicated to 22 stations across the country and its local viewership was greater than that of Captain Kangaroo and Sesame Street combined.

For 27 years, Captain Noah steered generations of little ones over "the most wondrous seas of a child's imagination" with gentle chats about kindness; patient instruction in how-to art projects; recitations of original poetry; and funny banter with the show's many puppets, like Maurice the Mouse and Wally the Walrus.

Each show closed with crooner Andy Williams' recording of "Sing a Rainbow" - a celebration of diversity before diversity was a buzzword. The song became the soundtrack to many a childhood, including mine and those of my eight siblings.

(To roller-skate down Memory Lane, grab a Kleenex and go to https://youtu.be/bND0DSUiHNk.)

Merbreier has outlived most of his former TV colleagues and friends, so obit writers may be at a loss to find people able to give a rich accounting of his life.

In the last few weeks, he has been distributing to the media a paperback version of his 2014 Kindle book, Captain Noah and His Magical Ark: Remembrances and Ruminations About the Animals and the Guests - Celebrities, Sports and Music Stars - Who Prowled Our Decks.

When he passes away, he wants to make it easy for journalists to select highlights from his TV career to include in postmortems of his days on the Ark.

Well, that's thoughtful, I tell Merbreier. But I don't want to wait until he's gone to share his memories with readers.

"I mean, you're Captain Noah and you're still here!" I say to him, remembering with a pang how shiny bits of my childhood died when other kids' TV icons passed away, like Chief Halftown (in 2003) and Sally Starr (2013). "I think people would love to hear your stories now."

That's how I've come to be at Shannondell, the retirement complex in Audubon, where Merbreier lives alone in a big, sunny apartment in a mid-rise building.

His lovely wife, Pat - known to audiences as "Mrs. Noah" - died in 2011. She had been the cohost of the TV show, its puppeteer, and the love of Merbreier's life.

"I miss her every day," he says. "That's the blessing and curse of living and working with your spouse: You get to spend all your time with them, but you miss them terribly when they're gone."

Merbreier does not want this column to be about the "slumped-over, forgetful old man" he says he has become, so I won't dwell on his peskier age-related infirmities. Suffice to say that his gloriously puffy sideburns are gone, his shock of white hair has thinned. He relies on a walker to move around his apartment.

But he is handsome and courtly in meticulously pressed trousers and an elegant blue sweater, and his comfortable home is stunning. Its walls are covered in beautiful artwork (including his own), and every corner and cabinet is crowded with mementos. (I lost count of all the miniature arks.)

"I have had a wonderful life," Merbreier says.

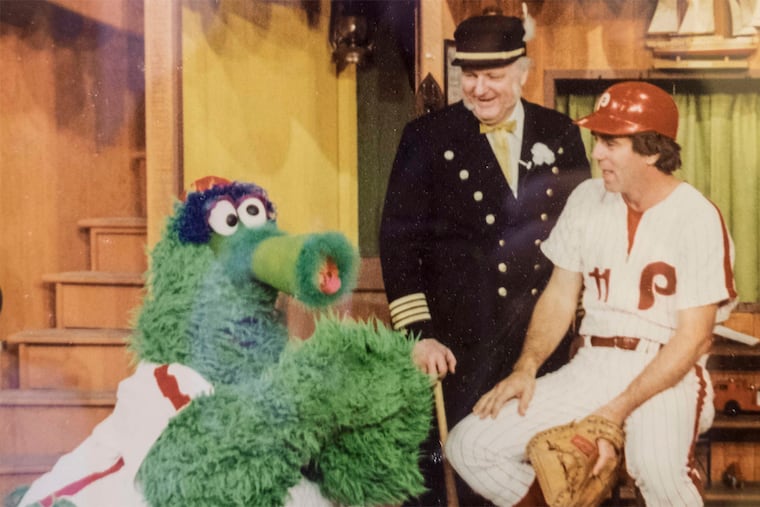

His book of memories only bobs on the surface of his years on the fictitious seas, but it captures Merbreier's sense of fun and purpose, a mission that was elevated every time a celebrity visited his show.

There was Stevie Wonder, who told Merbreier, "You remind me somehow of my daddy."

And John Lennon, who affectionately referred to Merbreier as "Captain Fred," the bridge commander in the Beatles' animated film, Yellow Submarine.

And Nepalese sherpa Tenzing Norgay, who climbed Mount Everest with Sir Edmund Hillary. A small, wiry man, Norgay demonstrated his strength by carrying the 225-pound Merbreier with ease across the set of the ark.

And there was a 9-year-old future celebrity named Jonathan Leibowitz, a trumpeter with the Kids Jazz Band from East Orange, N.J., who followed Merbreier all over the set the day the band played on the show.

"I liked him," writes Merbreier. "He had personality. He was smart. Not smart-alecky."

The kid eventually changed his name to Jon Stewart and went on to host The Daily Show on Comedy Central for 16 years.

(Note to Stewart: If you hit me up, I'll put you in touch with the captain himself.)

Merbreier's wife was delighted by all the stars but had a special affection for Peter Falk, the rumpled-detective star of TV's Columbo. The two enjoyed a great rapport.

"I was not surprised that they died on the exact same day of the exact same disease: Alzheimer's," writes Merbreier.

"I buried Pat with her sailor's hat. I hope Mr. Falk went with his raincoat."

But Merbreier clearly relished more the "everyday stars" he met as a local celebrity.

Like the nice family that opened its home to him during a July Fourth parade in Upper Darby when he urgently needed to use a bathroom midway through a parade he was grand-marshaling.

And the special-needs kids he had on his show so that able-bodied viewers would see that kids are more than their disabilities.

And all the children who sent their hand-drawn pictures to "dear old Captain Noah."

"They sent in their felt-tip and crayon works and pencil-scribbles on 'canvases' of shirt-cardboards, shopping bags, flattened shoe boxes, food-stained lunch-bags, and in one case a decorated piece of plaster cast from a broken leg," writes Merbreier. "We hung 'em all, as best we could."

For a man who was mobbed for decades at parades, in restaurants, when he was out shopping or attending public events, the quietness of life these days must seem odd, I say to Merbreier. He counters that he is at great peace, happy to be "antisocial" at the retirement complex, where he's nonetheless well-known and held in deep affection.

He stays in close touch with his only child, Pam, who lives in London with her two children and four grandchildren.

"Have you ever thought about moving to England, to be with them?" I ask Merbreier as he describes the joy of their last visit together, his great-grandchildren riding his motorized scooter around Shannondell.

"I never want to move from the Philadelphia area," he says. "You love that which is closest to you. This is where I lived with Pat.

"I have dreams about her, where I meet her on the other side of the door. The other night, I dreamed we had a typical married couple's argument and I thought, 'Gee, if I'm gonna spend eternity with her, I can't be arguing with her. God wouldn't like that at all, in heaven!' "

I think God would readily forgive any spats Merbreier got into. And then he'd thank Merbreier for ending every episode of Captain Noah - all 3,600 of them - with the same dear farewell.

"Be good to one another," Captain Noah told his young friends. "And don't forget to say your prayers."