Farmers Of the Year

Hundreds of children picked pumpkins off vines. They fed goats using a pulley system. They navigated a corn maze at the King family's Green Ridge Farm.

Hundreds of children picked pumpkins off vines. They fed goats using a pulley system. They navigated a corn maze at the King family's Green Ridge Farm.

Elias King said watching the children play on the Parkesburg farm during the fall gave him deep satisfaction. "It fills that void, because I don't have children of my own," said King, 37, who lives with his wife, Rebecca, in a house next to the farm. "To fill that craving, we're doing what we're doing."

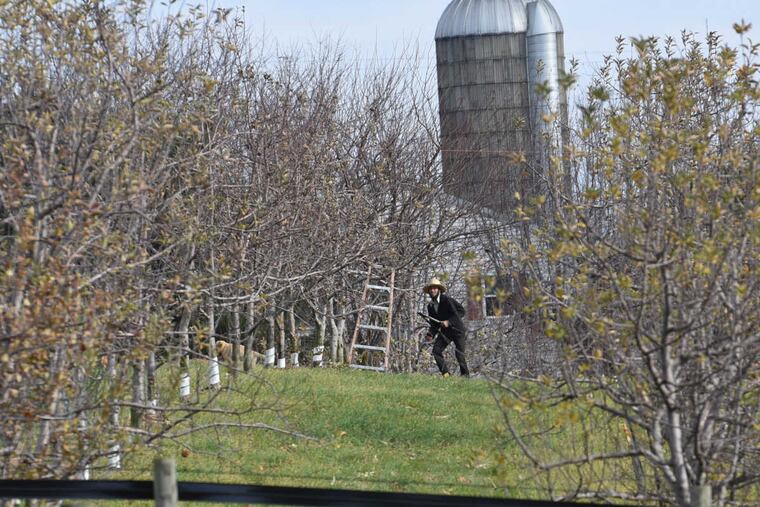

Chester County officials like what the Kings are doing so much that they have awarded the couple the county's Farmer of the Year award. What is especially significant about the citation is that the Kings are the first Amish farmers to win the honor since its inception in 1989.

Their farm, more popularly known in autumn as King's Pumpkin Farm, is an example of the reinvention of Amish agriculture over the last generation, said Steven Nolt, senior scholar at Elizabethtown College's Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies and a professor of history and Anabaptist studies.

For example, Amish farmers are embracing organic farming, specialties such as beekeeping and maple syrup production, and activities for the community at large, he said.

"They are trying to do things to try to keep farming sustainable and profitable while maintaining a lot of technological restrictions that are in line with their church," Nolt said, adding that some use limitations to their benefit.

The King family started its pumpkin business in 2003 after growing the gourds for a neighboring farm that no longer needed them. The family decided to keep them to sell, since transporting them miles away would be impractical with a horse and buggy. Pumpkins became a key part of the farm's identity.

The Kings' farm offers hayrides, apple cider doughnuts and other fall staples, and a petting zoo, which started with a pet goat in 2003 and has grown to three-quarters of an acre of goats, donkeys, chickens, ducks, and potbellied pigs, available for feeding from May to October.

Western Chester County is part of the Lancaster settlement of the Amish, which has more than 30,000 members and is the largest settlement by population, according to Erik Wesner, an author, editor of AmishAmerica.com, and former fellow at the Young Center. Between 10 percent and 20 percent of the Lancaster Amish community lives in Chester County, Wesner said.

Nearly 70,900 Pennsylvanians are Amish, which is 23 percent of the Amish population in North America, according to the Young Center. Nearly two-thirds of the continent's Amish population lives in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana.

Amish farmers own at least a quarter of the more than 430 preserved farms in Chester County, according to Geoffrey Shellington, agricultural programs coordinator for the county's Department of Open Space Preservation, who nominated the Kings for this year's award from the county's Agricultural Development Council.

"They do what they do and do it to the best of their ability because they love their farm and love what they do," said Shellington, describing the family as humble.

King's family began a dairy operation at the farm in 2001 that his sister and brother-in-law manage. They sell milk in Gap, Lancaster County, at Hillside Bulk Foods. The family also grows corn, soybeans, and wheat.

County officials also lauded the Kings' farming practices, including strip-cropping, alternating crops in strips to prevent soil erosion. The Kings use a rotating system for pastures that cattle use to graze and practice no-till farming, in which farmers drill seed into the ground for less disturbance to the earth.

They also have branched out into other farm-related enterprises.

King's wife bakes honey wheat bread to sell Fridays and Saturdays and sells Christmas wreaths.

A finished shed just beyond the farm's entrance sign and down a gravel road is the farm's small store. The "self-serve" shop runs on the honor system. Customers take produce - such as eggs, jams, squash, and cheese - and shove their money through a slot in the countertop. When King finds the time to be there, customers leave their money in a box.

"I was always happier if I had too much to do," King said, "instead of not enough."

610-313-8207 @MichaelleBond