Tyrannical Mafia boss Nicodemo 'Little Nicky' Scarfo, 87, dies in prison hospital

Nicodemo "Little Nicky" Scarfo, the tyrannical mob boss who ruled the Philadelphia underworld in the 1980s, has died while serving a 55-year prison sentence at a federal medical center in North Carolina. He was 87.

Nicodemo "Little Nicky" Scarfo, the tyrannical mob boss who ruled the Philadelphia underworld in the 1980s, has died while serving a 55-year prison sentence at a federal medical center in North Carolina. He was 87.

Once described in a government sentencing memorandum as "a man who sought and achieved a career in the major leagues of crime," Scarfo was considered one of the most violent organized crime leaders in the country.

Michael E. Riley, a lawyer for Scarfo's son, Nicodemo S. "Nicky" Scarfo, said Sunday that the elder Scarfo died at the Federal Medical Center in Butner, N.C., over the weekend. Riley was not certain of the time or cause of death, but said that Scarfo, 87, had been "in deteriorating health for awhile" and that he heard about Scarfo's passing on Saturday.

Norris E. Gelman, Scarfo's longtime lawyer, said he believed the cause of death was cancer. He did not know which type.

Scarfo was serving a 55-year sentence on racketeering and murder charges.

A family friend and criminal defense lawyer for the younger Scarfo discussed the elder Scarfo's legacy on Sunday.

"His legacy, if you can call that, as a ruthless mob boss is unparalleled, certainly in this area," said James J. Leonard Jr. "Nicky Scarfo was the epitome of a gangster in every sense of the word.

"What he leaves behind in terms of his actual family, his legacy there, sadly, leaves a lot be desired."

David Fritchey, the former head of the Organized Crime Strike Force in the U.S. Attorney's Office in Philadelphia, called Scarfo "bloodthirsty" and said his penchant for violence not only was detrimental to the city, it also contributed toward factionalism and distrust within his own organization. "I think his family will certainly mourn his passing, but on the whole, the city wasn't a better place for him having been here," Fritchey said.

Scarfo rose to power during one of the bloodiest periods in Philadelphia organized crime history. Twenty-five mob members or associates were murdered between 1980 and 1985 as the diminutive Scarfo, who stood just 5-5 and weighed 130 pounds, took control of the South Philadelphia-based crime family.

Scarfo's penchant for violence and hair-trigger temper were legendary both in the underworld and in law enforcement circles and they ultimately led to his downfall and the destruction of his organization.

Scarfo was described by former associates as a man who enjoyed his notoriety. He often described himself as a "gangster" and relished his image as a tough guy, fashioning his lifestyle after that of the infamous Chicago mob boss Al Capone and the cinematic characters portrayed by one of his favorite actors, Humphrey Bogart.

Scarfo named his waterfront home in Florida "Casablanca South" and christened a 40-foot cabin cruiser he kept docked behind the property "Casablanca Usual Suspects," both references to the classic Bogart film that he loved.

In addition to Bogart films, one of his favorites was Viva Zapata, a Marlon Brando film about the life and times of Mexican revolutionary Emiliano Zapata. He was also an avid boxing fan and chess player, having learned to play chess during an early stint in prison.

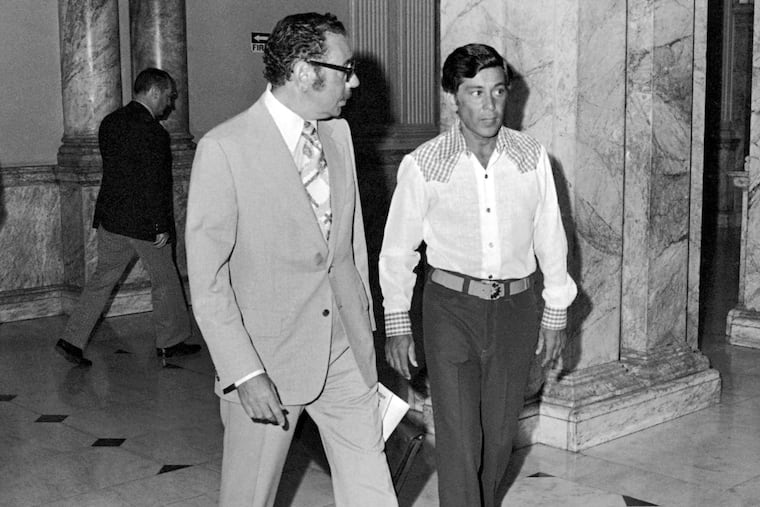

Well-groomed and always meticulously dressed, Scarfo relished his role as a Mafia don. It was more than just the power and wealth, associates said. After years as a lowly soldier in the Philadelphia mob, he took great satisfaction in the notoriety and celebrity that came with the top spot in the organization. And he took pride in the fact that he had had to climb over the blood-splattered bodies of former associates to get there.

Scarfo frequently boasted to associates about the murders he committed and about his guile and cunning in the underworld. And for years, law enforcement officials concede, he got away with murder. Scarfo was tried and acquitted twice for gangland slayings and was a suspect in several others. Only after two high-ranking members of his organization began cooperating with authorities in 1986, however, were law enforcement investigators able to gather enough evidence to bring him down.

"His exercise of naked, brutal power destroyed whatever loyalty he may have fostered in his subordinates and caused some to look to law enforcement for protection," read a 1987 report by the Pennsylvania Crime Commission that assessed the reasons for the demise of Scarfo and his mob family.

Between 1987 and 1989, Scarfo was convicted three times - for conspiracy, racketeering, and first-degree murder - and was sentenced to consecutive terms of 14 years, 55 years and life, although the life sentence was later overturned.

He and seven associates had been convicted in Common Pleas Court of plotting the 1985 murder of well-known South Philadelphia gambler and mob associate Frank "Frankie Flowers" D'Alfonso, but they later won a new trial and were acquitted. The racketeering charge stemmed from a federal trial in which Scarfo and 16 associates were charged under the Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act with murder, extortion, loan-sharking, gambling and drug dealing. Among other counts, the jury found Scarfo guilty of ordering nine murders and of four attempted murders.

His victims included an Atlantic County municipal court judge, an Atlantic City cement contractor, a Philadelphia drug dealer, several mob associates and the son of one of his oldest and most influential mob mentors.

Nicodemo Scarfo is a "remorseless and profoundly evil man," federal prosecutors told a judge at the time of his sentencing for that racketeering conviction. "His life has been committed to the Mafia and all the negative values it represents: greed, viciousness, treachery, deceit, and contempt for the law..."

Mob watchers who followed the rise and fall of Little Nicky said he epitomized organized crime in the 1980s. They said he was the underworld's reflection of the pinstriped outlaws who during that same time period were ravaging Wall Street and gutting the nation's savings and loan associations. The same philosophy seemed to be at work in the nation's financial circles and in the underworld: greed and the raw exercise of power were good; playing by the rules was for suckers.

"He thought he could do whatever he wanted," said Nicholas Caramandi, a former crime family soldier who became a government witness and testified against Scarfo.

All of that ended after his arrest in 1987. His last years were as a federal prisoner, number 09813-050.

No stranger to life behind bars, Scarfo had been jailed on three other occasions during his storied criminal career, in 1963, following his conviction on manslaughter charges in Philadelphia; in 1971, after being cited with contempt for refusing to testify before the New Jersey State Commission of Investigation; and in 1982, following his conviction on a gun law violation. None of those prison terms, however, lasted more than two years.

Scarfo was born in Brooklyn but grew up in South Philadelphia, where his family had moved when he was 10. His parents were Italian immigrants who hailed from Calabria, a dirt-poor region in southern Italy. Scarfo graduated from Benjamin Franklin High School, fought as an amateur boxer and worked for a time as a distribution supervisor for newsboys at Philadelphia's 30th Street train station.

According to most law enforcement accounts, he was introduced to the ways of the Mafia by his uncles, Nicholas, Joseph and Michael Piccolo, who were made members of the Philadelphia mob. Scarfo began as a bookmaker.

The Piccolo brothers ran Piccolo's 500, a restaurant at 11th and Christian Streets in South Philadelphia that for years was a well-known mob hangout. Nicholas "Nicky Buck" Piccolo rose to the rank of capo, or captain, under Philadelphia mob boss Angelo Bruno, who reigned as Mafia kingpin between 1959 and 1980.

Scarfo's standing with Bruno, however, was less secure.

His volatile temper and violent outbursts ran counter to the style and philosophy of Bruno and several other top mob figures, including Joseph "Mr. Joe" Rugnetta, the longtime consigliere - or counselor - of the Bruno crime family. In fact, according to several mob informants, Rugnetta had recommended several times that Scarfo be killed because of the problems and unwanted publicity he created for the otherwise low-key Bruno organization.

Bruno, ever the diplomat and master of compromise, opted instead to banish Scarfo from the city. This came in 1964, after Scarfo completed a one-year sentence following his conviction of manslaughter. The charge stemmed from a fight in the Oregon Diner in which Scarfo stabbed a longshoreman, William Dugan, during a dispute over a booth in the popular South Philadelphia restaurant.

In 1964, Scarfo moved to Atlantic City, where his mother, Catherine, owned and operated a boarding home on North Georgia Avenue in the predominantly Italian American Ducktown section of the resort. Scarfo lived with his second wife, Mimi, and three sons (one from an earlier marriage) in an apartment in his mother's building. Years later, after earning millions as a Mafia boss and maintaining a lavish waterfront home in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., Scarfo continued to list the Atlantic City apartment as his residence. And at one point told probation authorities that he worked as a maintenance man for his mother.

Scarfo struggled during his early years in Atlantic City. He was the mob's caretaker in a resort that was clearly on the skids. According to law enforcement accounts, he worked as a bartender and scrambled to make ends meet by engaging in some bookmaking and loansharking. For a time he also held an interest in an adult bookstore.

It was during this period that he was sentenced to a year in prison for refusing to testify before the SCI. He was one of nearly a dozen mob figures, including Angelo Bruno, jailed for contempt at that time.

In 1976, New Jersey voters gave Atlantic City the chance at a new life and, inadvertently, paved the way for Scarfo's rise to power. Voters approved legalized casino gambling for the city and opened the door to massive redevelopment. Scarfo became the mob's man on the scene and reaped the benefits. Both his financial situation and his standing within the organization improved as a result.

Two mob-linked construction companies controlled by Scarfo associates did several million dollars in subcontracting work on casino and public works project spawned by the development boom. Labor racketeering and political corruption brought even more money the mob's way. In one glaring example, documented in investigations by both New Jersey gaming regulators and the FBI, Scarfo managed to seize control of the largest labor union in Atlantic City, Local 54 of the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees International Union.

Authorities charged that the union, which represented about 18,000 casino-hotel workers, was secretly run by the mob boss who approved all major appointments and who pocketed $20,000-a-month illegally siphoned from the union's bulging coffers. Two successive presidents of Local 54 were forced to step down because of their alleged ties to Scarfo and, in 1990, following an out-of-court settlement of a civil racketeering suit brought by the U.S. Attorney's Office in New Jersey, a federal monitor was appointed to run Local 54 and rid it of mob control.

Scarfo's expanding wealth and power during the early days of casino gambling in Atlantic City coincided with a bloody, internecine struggle for control of the Bruno crime family in Philadelphia. The first shots in that battle were fired on March 21, 1980, when Angelo Bruno was gunned down outside his home in the 900 block of Snyder Avenue in South Philadelphia.

While most law enforcement officials believe Scarfo had nothing to do with that murder or a series of retribution killings that followed, he clearly was the mobster who benefited from the turmoil that rocked the underworld and left a generation of potential leaders dead.

Bruno was succeeded by Philip "Chicken Man" Testa, a friend and mob mentor of Scarfo's. Testa elevated the Atlantic City mob soldier to the rank of family consigliere and together, Testa and Scarfo established a reign of terror in the underworld.

Bruno had operated for years in the shadows, depending on negotiation and compromise to keep his organization running smoothly and out of the limelight. Testa and Scarfo brought blazing guns, public executions, and flash and glitter to the Philadelphia mob.

This new style was epitomized by the brutal Christmas-time slaying of Philadelphia Roofers Union boss John McCullough, who was gunned down in the kitchen of the Bustleton home by a poinsettia carrying deliveryman. McCullough was killed, law enforcement authorities later learned, because he had tried to wrest control of a part of the Atlantic City bartenders union from Scarfo.

Violence continued to rock the Philadelphia underworld for the next five years. Philip Testa was blasted out of power by a bomb his rivals planted under the porch of his South Philadelphia home. Scarfo assumed the top spot in the organization, and with Testa's young and charismatic son, Salvatore, as his top gunman, proceeded to avenge the Testa murder and solidify his hold on the organization.

Ten prominent South Philadelphia mob figures were killed in the two years following Testa's death as a faction of the organization loyal to Scarfo did battle with a rival group headed by old-time mob leader Harry Riccobene. Scarfo managed to sit out most of the Riccobene War, as it came to be called, in a federal prison in Texas where he served 17 months on a gun law violation. From his prison cell, authorities later charged, he continued to run the organization and to issue murder contracts on his rivals.

Released in January 1984, he returned to Philadelphia as the undisputed boss of the crime family and the kingpin of an ever-growing and prosperous mob syndicate. Teams of Scarfo henchmen had instituted a "street tax" in the underworld. This was a weekly or monthly extortion payment demanded of bookmakers, loan sharks, and drug dealers. At its peak, the tax brought in thousands of dollars per week to the Scarfo organization.

While the systematic extortion made Scarfo a wealthy man, it served to destabilize the underworld and set the stage for the mob's eventual downfall. Murder had been the negotiating tool of last resort during the Bruno era. It became the calling card for the Scarfo organization. Bruno had emphasized loyalty and respect, albeit among criminals. Scarfo ruled through fear and intimidation.

Any real or imagined slight could set off the volatile little mob despot, former gang members later told authorities. Paranoia and treachery were rampant within the crime family.

"He could turn on you in a second," said Caramandi, the former Scarfo family soldier who became a government witness. "And once he did, forget about it. It was all over for you. You might as well go to China."

In 1984, in an act of treachery that came to symbolize the era, Scarfo turned on Salvatore Testa and ordered him killed. After six months of plotting and several botched opportunities, the murder was carried out in September of that year. Testa was gunned down in a candy store on East Passyunk Avenue and his body later dumped on the side of a dirt road in Gloucester Township, N.J.

Scarfo ordered Testa killed, mob informants later told authorities, because he had offended mob underboss Salvatore "Chuckie" Merlino by breaking off his engagement to Merlino's daughter, Maria, just two months before they were to be married. But others within both law enforcement and the mob believe Scarfo's real motive was fear that the young and charismatic Testa would eventually become a rival for power within the organization.

Testa's father, Philip, had shepherded Scarfo through the dangerous and often fatal internal politics of the mob. It was Philip Testa who shielded Scarfo from the wrath of Joe Rugnetta back in the 1960s.

Scarfo repaid the favor, law enforcement officials said disdainfully, by ordering Testa's son killed.

"There was no logical reason" for the Salvatore Testa murder, mobster Thomas "Tommy Del" DelGiorno told authorities in 1986 after he, like Caramandi, began cooperating.

DelGiorno and Caramandi had served as Scarfo hitmen during the mid-1980s. But in 1986, both found themselves out of favor with the mob boss. DelGiorno, who had risen to the rank of capo, was the central figure in a major New Jersey State Police gambling investigation. Caramandi was the key player in a botched $1 million extortion. Both came to believe they were marked for death by Scarfo and both decided their only chance for survival was to cooperate with authorities.

Together the two mobsters testified before dozens of grand juries and at nearly as many trials. From the witness stand, they painted a picture of the Scarfo crime family and the murderous mob boss who ran it. Their testimony led to the convictions that brought Scarfo and his organization down.

Scarfo was arrested in January 1987 at the Atlantic City airport in Pomona, N.J., as he returned from a holiday stay at his Ft. Lauderdale residence. The mob boss, handcuffed and lead out of the airport terminal to a waiting FBI car, would never spend another day as a free man.

Over the next two years, he was shuttled between his prison cell and a series of court appearances. In 1989, following three convictions and related sentencings, he was shipped to the federal penitentiary at Marion, Ill.

The rise and fall of Little Nicky Scarfo took on the elements of a tragic Italian opera as it was played out in front page headlines and on television and radio news reports.

In 1988, in the midst of the highly publicized RICO trial, Scarfo's youngest son, Mark, then 17, attempted to commit suicide. He was found by his mother hanging from a noose rigged in the bathroom of a mob construction company office on North Georgia Avenue next to the apartment building where his family lived in Atlantic City. Rushed to the hospital, Mark Scarfo survived, but never regained consciousness. He died in 2014.

In 1989, shortly after being sentenced to 45 years in prison on racketeering charges, Scarfo's nephew and mob family underboss, Philip Leonetti, cut a deal and began cooperating with authorities. Of all the mobsters who "flipped" during the 1980s, Leonetti's defection was the most embarrassing for Scarfo.

Leonetti, nicknamed "Crazy Phil," subsequently admitted to participating in 10 murders while rising through the ranks of the Mafia. As underboss, he was privy to the inner circle of the organization and accompanied his uncle to several meetings with high-ranking members of the New York crime families. His role as a government informant and witness, particularly against the bosses of other organizations, made him a valuable and nationally significant mob turncoat.

In the underworld where Scarfo had built his reputation, this was anathema. In a comment to a private investigator in 1991, Scarfo caustically referred to Leonetti as "my former nephew."

"He's got a new uncle now," the investigator said Scarfo told him. "His name is Uncle Sam."

Leonetti's defection came at about the same time Scarfo's oldest son, Christopher, had his name legally changed. Chris Scarfo, an Atlantic City real estate broker, wanted no part of his father's "business," according to law enforcement and mob sources alike. So he petitioned Atlantic County Superior Court and assumed the maiden name of his wife. Both he and his son no longer use the Scarfo name.

Staff writers Chris Palmer and Rob Tornoe contributed to this article.