3D model offers detailed look at 1876 Centennial Expo

Surrounded by construction inside a climate-controlled room at Fairmount Park's Memorial Hall is a long-forgotten Philadelphia treasure: a three-dimensional "snapshot" of the Centennial Exposition as it looked on Independence Day in 1876.

Surrounded by construction inside a climate-controlled room at Fairmount Park's Memorial Hall is a long-forgotten Philadelphia treasure: a three-dimensional "snapshot" of the Centennial Exposition as it looked on Independence Day in 1876.

People who saw the model for the first time were astounded.

In intricate detail, it depicts the nation's 100th-anniversary celebration in full swing, with Philadelphia at the epicenter, attracting millions from around the world.

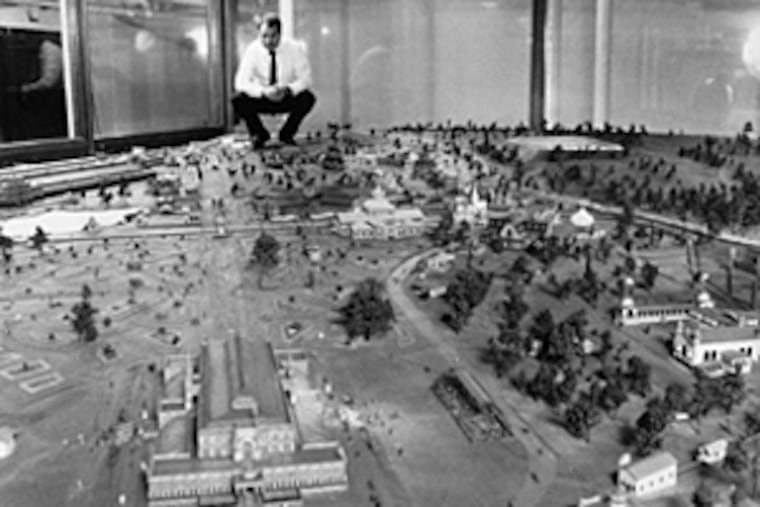

The model spans 20 by 40 feet, with buildings, trees and people all rendered in miniature. A strange-looking monorail, steamboat ferries and scores of gingerbread-style buildings depict a Victorian-era Disneyland.

Today - 131 years after men wearing straw hats and women wearing hoop dresses and parasols roamed the exposition grounds - only two of the exposition's 200 structures are left: Memorial Hall and the Ohio House. And they're headed, along with the unique model, into a new era.

Once neglected and vandalized, Memorial Hall is getting a $40 million facelift that will transform it into the home of the Please Touch Museum in fall 2008. The model will be the centerpiece of a new Centennial exhibit.

The restoration has long been the dream of Philadelphia historians, preservationists and architects who hoped to save the Beaux Arts building, originally designed by Hermann J. Schwarzmann as an international art gallery and permanent Centennial memorial. They carefully researched the history of Memorial Hall and the Centennial; they studied the model and photographs, and they are lovingly restoring the architectural gem to embrace its role as a children's museum.

Nearby, the Gothic-style Ohio House - that state's exhibit space in 1876 - is being turned into a cafe, which is expected to open this summer.

"I actually get emotional about this," said Nancy Kolb, president and CEO of the Please Touch Museum. "I have always loved history and have had a long career in museums, so to save this building and tell the story of the Centennial is great for me. And the model is a key part of what we're trying to do."

Kolb, a former member of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, said much attention is focused on 18th-century Philadelphia, but little is given to the 19th-century Centennial, which drew 10 million visitors at a time when Philadelphia had less than 1 million residents.

In the summer of 1876, Philadelphia replaced Niagara Falls as the most popular honeymoon spot.

"What happened in Philadelphia is a story we need to know," she said. "It was an opportunity for the city to shine and it did. It was America's explosion on the world scene.

"The model is a record of that time; to me, it is the second most important object in the city, after the Liberty Bell."

Nobody had attempted anything like the Centennial Exposition. The sheer magnitude of it was mind-boggling.

Planners created a self-contained city on the Belmont Plateau of Fairmount Park, with massive buildings, police and fire departments, a water and sewer system, roads and public transportation, including the first monorail in North America.

"It's amazing to think that all of this was here and most of it is now gone," said Stacey Swigart, curator of collections at the Please Touch Museum, as her eyes scanned the model in a huge glass case.

The nation's 100th birthday came during the Gilded Age in America. It was a year of the corrupt politician Boss Tweed, the Molly Maguires, the Whiskey Ring and "Custer's last stand." Many people turned out to hear Dwight Moody's gospel message and Thomas Huxley's lectures on natural selection. The Philadelphia Athletics were playing. Football was catching on. And Tom Sawyer was a popular new novel.

It was an optimistic, "can-do" time, and the celebration "didn't happen in Chicago or New York," Kolb said. "It happened here. I hope, as we tell the story, it will be a matter of Philadelphia civic pride."

The city was ready to party on July 4, 1876. Even with temperatures in the 90s, the fair drew large crowds to 60,000 exhibitors, some from as far away as Siam and Australia.

In Center City that morning, 10,000 troops marched down Chestnut Street to the music of military bands. The neat ranks of soldiers passed a bunting-festooned platform at Independence Hall, where they were reviewed by Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman.

Official ceremonies got under way at 10 a.m. at Independence Square, filled to overflowing with 50,000 people. In an emotional high point, Richard Henry Lee, grandson of a Declaration of Independence signer by the same name, stepped forward to read the revered document, said Swigart, who spent years researching the Centennial.

About the same time, activist Susan B. Anthony marched in, uninvited, to read her own declaration of women's rights and to present a petition demanding suffrage, Swigart said.

As the emphasis of the celebration shifted to the Centennial Exposition, fair-goers viewed art works at Memorial Hall and wandered outside to see the arm and torch of the Statue of Liberty on display.

They admired a statue of a Civil War soldier in front of the building. They watched artists sketching the fair; photographers at work; carriages and steam engines passing, and crowds entering the vast, majestic Main Exhibition Hall, then among the largest buildings - if not the largest one - in the world.

Just west of Memorial Hall, many flocked to the July 4 dedication ceremony for the Catholic Total Abstinence Fountain, which today is adjacent to the Mann Music Center.

On display in Agricultural Hall was a confectionery exhibit of historical figures in chocolate and sugar. They included Chief Sitting Bull and Gen. George Armstrong Custer. News of Custer's downfall, along with more than 200 members of the Seventh Cavalry, had just filtered to Philadelphia.

A massive fireworks show lighted the night sky and drew oohs and ahs.

John Baird didn't want the country to forget the excitement of that day.

A former member of the Centennial Finance Committee who raised money for the exposition, Baird spent $25,000 of his own money to pay for a model of the fairgrounds.

When it was unveiled in 1889, after thousands of hours of work, people were simply astonished.

"There before them," the Public Ledger reported, "was everything that was in that [exhibition] enclosure of 236 acres - every one of the nearly 200 buildings, from the 'Main Building' to the smallest edifices - every piece of open air sculpture, every statue, every fountain, every road and path and lake . . . "

Baird's spectacular model had captured a moment, like a photograph taken from a hot-air balloon high above the Centennial fairgrounds.

"The purpose . . . was to preserve in permanent form architectural thoughts and ideas that cost a great deal of money and effort, and that it would be difficult to hand down to future generations for their instruction in any other way," Baird wrote in 1889.

The model had been a massive undertaking. Baird, a Philadelphia marble magnate, collected photographs, maps and architects' drawings, then hired artisans to begin the delicate work of recreating the exposition to scale: One foot in the model represented 192 on the fairgrounds.

Buildings were hand-carved in wood, assembled like hobby models, and painted in the same colors as the originals. The rolling landscape, roads, rail lines - even an experimental steam-driven monorail that crossed a gorge - were duplicated in minute detail.

The model was given to the city in 1890 and for the next five years was displayed at the Spring Garden Institute, a technical school where Baird served as an officer.

It was exhibited at City Hall from 1895 to 1900, when it was moved to Memorial Hall in what was the old Pompeiian Room in the basement.

And there it was largely forgotten while park and city officials tried to find a suitable role for Memorial Hall.

The granite building had many lives over the years, said Barry Bessler, chief of staff for the Fairmount Park Commission.

It housed art collections until 1954, when it was closed as a museum and turned over to the park commission. For the next four years, the venerable building was vacant, but was later renovated and used for park offices.

The Great Hall, with its inlaid marble, translucent green dome and creamy Victorian stucco work, became a popular site for public functions and parties. Other parts of the building housed a swimming pool and gymnasium.

"We had our [park] offices there for over 50 years, but the building required significant restoration that we were not able to provide," Bessler said.

John Gallery, executive director of the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia, an advocacy group for historic buildings, remembered going to a costume ball there in 1969.

"The building then was under-used and in poor condition," he said. "It's been a long, long story of never finding the right use to restore and maintain the building.

"Some buildings are interesting, because of their great architecture; some because of the stories behind them. Memorial Hall is interesting for its architecture and history."

Attempts were made over the past 25 years to restore the dome of the building. The Centennial model was repaired - at a cost of $50,000 - after vandals broke in and smashed two glass panels in 2005.

Then came the Please Touch Museum to the rescue with an 80-year lease on the building. The museum's efforts to move to Penn's Landing had fallen through in 2002 and Kolb was lobbying the Please Touch Museum board of directors to move to Memorial Hall. "It was built as a museum and it is going back to being a museum," Kolb said.

Plans are to return the building to its original grandeur. A 40-foot replica of the Statue of Liberty's arm and torch - made entirely of toys - will be placed in the Great Hall. And a newly restored 1924 Dentzel Carousel, made in Philadelphia, will be housed in a glass addition on the east side of Memorial Hall.

The dome is being refurbished again, said architect Jim Straw, whose firm Kise Straw & Kolodner is now working on the Memorial Hall makeover.

"What we have tried to do is use the building as a lens through which we view not only Philadelphia and its role during the Centennial celebration, but all the things the building has seen within it," he said.

"It's a national historical landmark. Just to have the honor of working on a building of this significance is career-defining, a project made in heaven."

Workers were finishing cleaning the dirty granite facade of Memorial Hall, and noisy front-end loaders and dump trucks were hauling away debris.

Inside the dimly lit basement, the model waited in its vault-like room to once again thrill the crowds with a special view of the nation's and Philadelphia's past.

"It seemed desirable," Baird wrote of the Centennial Exposition, "that all the thought, time and money expended in reaching such a good result should be preserved in some way for the information of coming generations, and no better way was suggested than that of making a miniature model."