Changing Skyline: Preservationists once bit, twice shy, over Boyd bill

Councilman Bill Green's proposal that would save the syncopated, jazz-age interior of the long-shuttered Chestnut Street movie palace along with the exterior is leading preservationists to err on the side of caution.

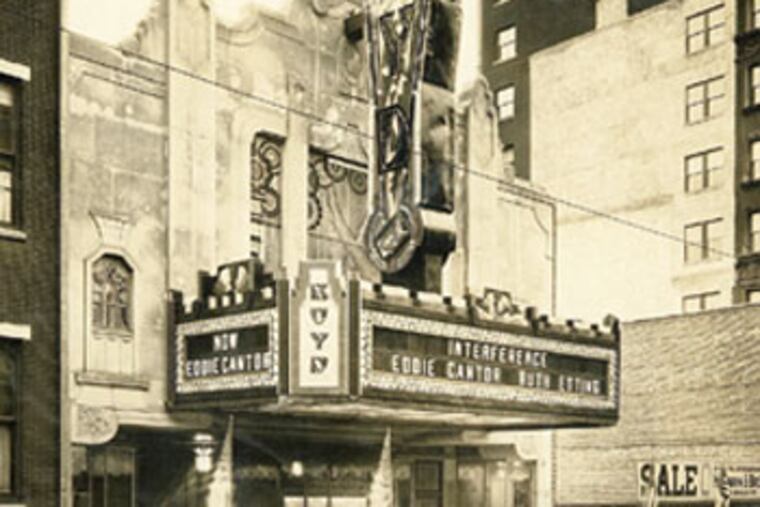

For nearly two decades, the Boyd Theater was a building that just couldn't get any love. One former owner went all the way to Pennsylvania's Supreme Court to reverse the theater's historic designation. Another wanted to raze the art deco movie palace. A couple of preservationists were even heard disparaging its charms.

Now, suddenly, everyone professes to love the Boyd.

They just can't agree on the best way to show it.

Credit the National Trust for Historic Preservation with changing the city's perceptions about the long-shuttered Chestnut Street movie house. When the group put the 1928 theater on its high-profile endangered list last month, it shone a spotlight on Philadelphia's neglect of its architectural treasure.

Before you could say "Roll 'em," the Preservation Alliance submitted a petition recommending that the Boyd's jaunty facade be protected with landmark status. Mayor Nutter, who has been trumpeting his pop-culture credentials, chimed in with vocal support for the nomination, along with memories of "first seeing the great film Rollerball" in the 2,350-seat, polychrome auditorium. (His phrasing suggests he enjoyed the 1975 dystopian flick more than once.)

But the boldest, and potentially most meaningful response, came from Councilman Bill Green. Since the Boyd is Center City's last surviving movie palace from Hollywood's heyday, he argues that it isn't enough to save the exterior. Its syncopated, jazz-age interior also needs to be shielded from potential destruction.

And pronto, too. The Boyd's owner, Live Nation, is evaluating bids from interested buyers. Anything could happen.

The problem is that Philadelphia's historic-preservation laws are famous for not protecting interiors. So Green decided to rectify that by introducing a bill that would make any of the city's great public spaces eligible for historic status. It would be the first major addition to the city's historic-preservation code since 1984.

Was he applauded for the move? Very, very politely.

Green's bill came up for a public hearing before City Council's rules committee yesterday, and you couldn't help noticing the ambivalent tone adopted by some of Philadelphia's most dedicated preservationists.

They ultimately persuaded Council to delay a final vote until Sept. 18. They aren't opposed to the bill, they insist. Just nervous.

The measure came out of the blue May 22, just two days after the National Trust's announcement, and took preservationists by surprise. Green's hard-driving timetable originally called for molding rough legal language into concrete city law in a mere three weeks.

That's fast work for even a minor piece of legislation. But for a history-making change to Philadelphia's preservation laws, such speed verged on the reckless.

Green's intentions were admirable enough. But, like it or not, the Boyd has a history that has nothing to do with its etched mirrors or its design by theater architects Hoffmann and Henon. The theater was the subject of a notorious six-year legal case that nearly destroyed America's historic-preservation laws. The experience cost a bundle and left preservationists scarred.

The trouble began in 1987, after the city Historical Commission gave the Boyd, then known as the Sameric, landmark status based on its stunning interiors. The case went to the state Supreme Court - twice - and finally ended in 1993 with the Boyd's designation being invalidated. No wonder preservationists panicked when they saw Green's bill.

Under his timetable, the measure would have become law before the Historical Commission ever had a chance to hold a public discussion. Without the commission's scrutiny, the bill would almost certainly have been deformed at birth, the Preservation Alliance's John Gallery predicted.

Green tried to argue that the speed was justified because of the uncertainty surrounding the Boyd's impending sale. His argument just wasn't convincing.

Though he may have pushed too hard, preservationists owe Green a debt of gratitude for taking up the cause. The benefits of his proposed law would extend far beyond the Boyd, offering protection to the sorts of interior spaces people think of when they think of Philadelphia: Wanamaker's grand court, the Ritz-Carlton Hotel's rotunda, 30th Street Station's waiting room.

Some less-well-known rooms, such as the old Jacob Reed store on Chestnut Street, the Corinthian Room in the former Strawbridge & Clothier building, or the Mask & Wig Club on Quince Street, also might qualify. Perhaps as many as 80 rooms in the city might be designated historic, Green predicted.

His bill intentionally limits protection to "publicly accessible" interiors and excludes private residences. But there remains a long list of unanswered questions: Should church sanctuaries be considered fair game for regulation? Will public spaces that have been privatized still be eligible for designation? Will the Historical Commission find itself dictating whether an owner can move the furniture?

Still, about 20 American cities already have similar laws, and several are far stricter than the one Green proposed. Those laws have withstood repeated tests from the courts. Philadelphia has allowed itself to be spooked by the Boyd debacle for too long.

Council's rules committee struck a good compromise by putting off the final vote until September. Now, it's up to the preservation community to make sure that Green's effort doesn't lose momentum over the long, hot summer.

Having waited two decades for a law on historic interiors, Philadelphia can surely wait three more months to make sure it's done right.

But not one minute more.