At trial, following a defrocked priest's 25-year trail

For weeks, jurors at the Philadelphia clergy sex-abuse trial have sat through a meticulous paper case, hearing painstaking recitations of every complaint, memo, or interview related to priests suspected, but not charged, with abusing minors over the last half-century. Time and again, one question has been left dangling: Where are these priests now?

For weeks, jurors at the Philadelphia clergy sex-abuse trial have sat through a meticulous paper case, hearing painstaking recitations of every complaint, memo, or interview related to priests suspected, but not charged, with abusing minors over the last half-century.

Time and again, one question has been left dangling: Where are these priests now?

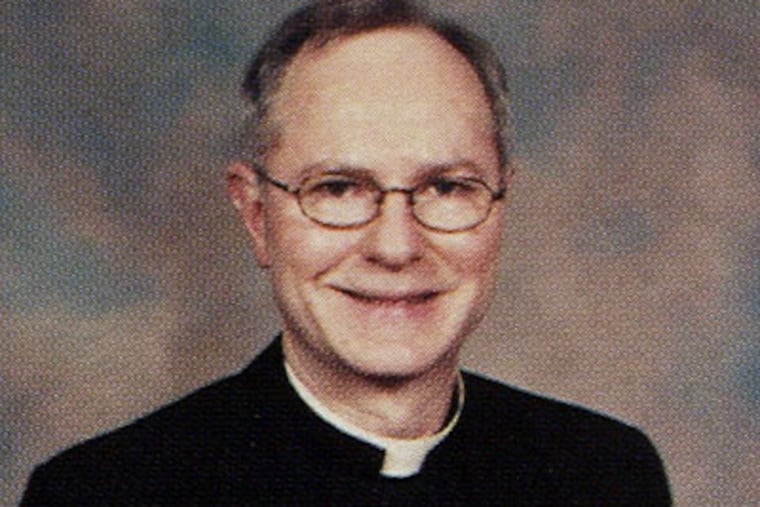

On Thursday, a prosecutor and an investigator sought to answer that at the start of their presentation on the Rev. David Sicoli, a former pastor who was transferred eight times in 25 years amid a trail of complaints about his infatuation and misconduct with teen boys.

Sicoli was removed from ministry in 2004 and defrocked four years later. Church officials ultimately logged at least 11 credible claims against him.

"Do you know where he is living?" Assistant District Attorney Mark Cipolletti asked Detective James Dougherty, who prepared the file on Sicoli.

"He lives across the street from the largest playground in Sea Isle City," Dougherty replied. The exchange underscored a point prosecutors have been trying to make in their endangerment case against Msgr. William J. Lynn: that he and other leaders at the Archdiocese of Philadelphia waited so long to act on proof or suspicions of misconduct that child sex abusers escaped civil or criminal consequences.

Some of those allegedly abusive priests mentioned at trial have died or agreed to live under supervision to keep their collars. Sicoli is one of at least six who simply retreated to private life. Some still live within the region.

Sicoli could not be reached for comment Thursday. Public records place him at a Sea Isle house he has owned for three decades. But the listed phone number was disconnected.

There is no record of accusations against Sicoli since he left the archdiocese. Defrocked priests are not required to register or notify their neighbors.

Still, the reference to an accused abuser living near a playground irked one of Lynn's lawyers enough that he seized on it as he launched his cross-examination.

"I assume that since you know that, you've called the police chief in Sea Isle City and told him that he's living there. Is that accurate?" lawyer Jeffrey Lindy asked the detective.

Dougherty didn't have to answer. Prosecutors objected and, after a closed-door conference, Common Pleas Court Judge M. Teresa Sarmina ordered the defense lawyer to move on.

Sicoli's tenure in the archdiocese dominated the last day of the fifth week of the landmark trial. He's one of 21 priests whose secret files prosecutors are showing jurors in a bid to prove Lynn routinely ignored or failed to investigate glaring signs that clerics were sexually abusing children.

In 1993, a year after he became secretary for clergy, Lynn had reviewed Sicoli's file and included him on a list of area priests who had been accused of sexual misconduct but whose cases lacked conclusive evidence.

Those allegations dated to 1977, just two years after Sicoli's ordination, according to the records shown to jurors. Three teenagers in the Catholic Youth Organization at St. Martin of Tours in Philadelphia complained to other priests that Sicoli had homosexual tendencies and acted inappropriately around them. One called Sicoli "sick," said the priest made him sleep in his bed on a trip to Florida, and "acted like Father was in love with him."

Weeks later, that boy retracted his allegations, saying he might have overstated them. Church officials transferred Sicoli months later to Immaculate Conception in Levittown, Bucks County, but recommended he not have any involvement with youth.

Within a few years, Sicoli was overseeing the parish altar-boy program, as well as its CYO and religion classes for public school children. And the same concerns emerged.

"I implore you to please help Father [Sicoli] before another school situation arises," the parish grade-school principal, Sister William Anthony, wrote in a 1983 letter to archdiocesan officials. "Father has had a controlled grip on [a] young fellow that is unhealthy for a 13-year-old."

After Sicoli became pastor of Our Lady of Hope in 1993, it was his fellow priests who started to complain. Sicoli spent countless hours in the presence of a young teen, a boy who dined with him and traveled to his Shore house.

According to the files, Lynn learned the boy's name from the parish staff but made no attempts to contact or interview him. "None. Whatsoever," the detective testified.

Lynn's lawyer noted that that boy never came forward. Lindy also pressed Dougherty to acknowledge that the first allegation of sexual abuse against Sicoli was filed — then retracted — about 15 years before Lynn took his post and the rest came after Lynn had left his post in 2004. In between, he said, there were no victim complaints.

"Actual victims? No, sir," the detective said. "But there were many reports from responsible adults regarding juveniles and Father Sicoli."

Some of those victims are expected to testify after the trial resumes next week.

Contact John P. Martin at 215-854-4774 or at jmartin@phillynews.com. Follow him @JPMartinInky on Twitter.

We invite you to comment on this story by clicking here. Comments will be moderated.