For juvenile lifer who killed policeman, 44 years to life

That's well above the standard 35-years-to-life deal many of Philadelphia's 300 other juvenile lifers have received, but far shy of the 60 to life prosecutors had sought.

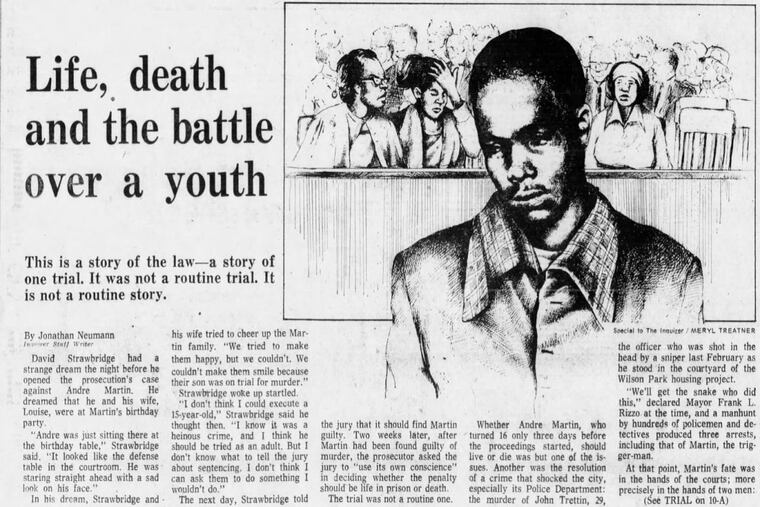

The 15-year-old Andre Martin who in 1976 waited for police to respond to reports of a shooting at a South Philadelphia housing project and then fired a bullet into the head of Philadelphia Police Officer John Trettin was an angry and out-of-control kid.

The 57-year-old who appeared in court Wednesday was a model inmate who had gone decades without a rule infraction, donated regularly to charity even on his 42-cents-per-hour prison wage, and expressed deep remorse for his crime.

In a resentencing hearing — pursuant to a U.S. Supreme Court determination that automatic life-without-parole sentences for juveniles are unconstitutional — Philadelphia Common Pleas Court Judge Barbara McDermott sought to reconcile the two. She gave Martin 44 years to life, making him eligible to seek parole in three years.

That's well above the standard 35-years-to-life deal many of Philadelphia's 300 other juvenile lifers have received, but far shy of the 60 years to life prosecutors had sought. Assistant District Attorney Chesley Lightsey said it was yet to be determined whether her office would appeal the ruling.

Although the Supreme Court decision emphasized a juvenile criminal's capacity for change, McDermott said she could not discount the nature of the crime.

"When you kill a police officer, a member of society whose goal it is to protect the public, it's a threat to all of us," she said.

It was the culmination of an emotional, two-day hearing in which prosecutors described the broad social harm of the crime and Trettin's three children testified to the devastating personal aftermath.

Lightsey spoke about how a case like this could undermine trust between disinvested communities and the police officers meant to protect them. "We can't even measure the impact this has had on society," she said.

And Trettin's youngest daughter, Wendy Callan, who was just 4 when her father was killed, described the grief that washed over her anew with every father-daughter dance and family milestone.

Worse, she said, "my brother" — just 10 months old when Trettin died — "has no memory of my dad. He never got to learn the things boys should learn from their dads: How to throw a ball, bait a fishing hook, the birds and the bees."

For the first time in 41 years, Martin stood in front of them and, weeping, searched for the words to apologize.

"By killing your father, I have hurt you every day and in so many ways," he said. "I think of the times you needed advice or a hug, or just the comfort of a loving father. I know I took that from you, and I'm sorry."

He added, "I'm getting this chance, and I'm so sorry it means you have to relive that awful night that gave you a lifetime of pain."

After the hearing, one of Martin's relatives embraced Wendy Callan as Martin's sister Kim stood by, her eyes red from crying.

"This is the Lord's doing, and he does things well," the sister said.

According to testimony, Martin's childhood was a difficult one.

He met his biological father for the first time in the courtroom during his murder trial. Over the two-day hearing, his siblings described an abusive home where they were beaten with electrical cords, belts, ashtrays, hammers, and anything else that was at hand.

A forensic psychologist, Steven Samuel, said Wednesday that such abuse, particularly when meted out whether or not a child has misbehaved, can trigger anger, paranoia, and violence.

"Kids can't figure out right from wrong," he testified. "You get very angry, and that anger has to go somewhere."

Defense lawyers sought to turn the focus to Martin's transformation. He aims, they said, not to just to speak of remorse but to embody it.

According to the Supreme Court, "the critical factor is not the circumstance of the crime, but whether the person is capable of rehabilitation," said Andrew Kantra, an attorney with Pepper Hamilton who represented Martin pro bono. "Andre is not just capable of rehabilitation. He is rehabilitated."

Eric Hall, a lawyer from Coopersburg, Lehigh County, described for the court the three months he spent in Graterford Prison while incarcerated for vehicular homicide, speaking with Martin for hours each day.

"He saved me," Hall said in an interview. "I wanted to commit suicide. I thought that would be the ultimate manifestation of remorse, and he told me it was the opposite. He said remorse isn't spoken, it's lived."

Hall said he grew up in Philadelphia and remembered being appalled by the news of Trettin's killing. "But then I met Andre and I saw who he was. Andre Martin was an oasis of humanity in the side yard at SCI Graterford. He taught me to be a responsible human. This community would be so benefited by his inclusion."

McDermott, however, said the circumstances of the case and questions about Martin's remorse gave her pause.

So, she told Martin, "I think you need a few more years."