He's been locked up 4 decades for killing a cop when he was a kid; is that long enough?

In the wake of a Supreme Court ruling that mandatory life-without-parole sentences are unconstitutional for juveniles, Philadelphia Common Pleas Court Judge Barbara McDermott will decide whether Andre Martin is due a second chance.

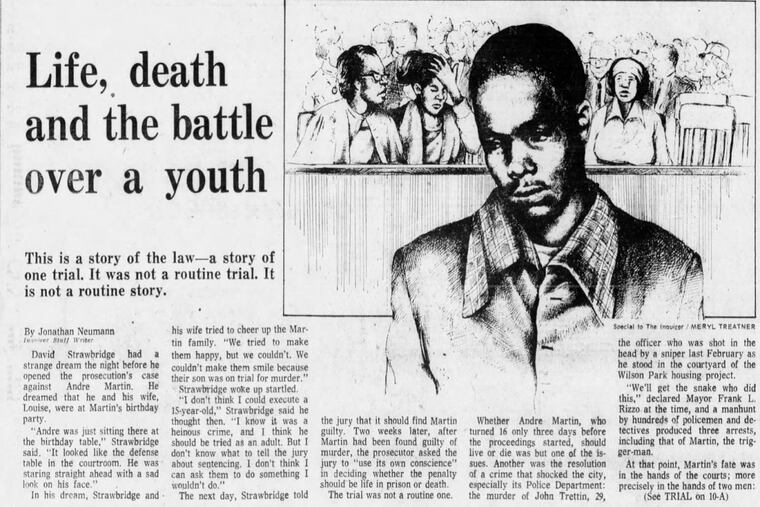

On Feb. 25, 1976, Police Officer John Trettin was called to the Wilson Park housing project in South Philadelphia to investigate reported gunshots. Then, a shot echoed from a high window. Andre Martin, who was just 15, had fired a bullet through Trettin's skull.

With that teenage act, two lives ended. Trettin died in Methodist Hospital four days later. Martin was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Now, in the wake of a Supreme Court ruling that mandatory life-without-parole sentences are unconstitutional for juveniles, Philadelphia Common Pleas Court Judge Barbara McDermott will decide whether Martin is due a second chance.

The District Attorney's Office, which initially planned to seek life without parole, has offered a deal for 60 years to life; that would still be the longest sentence yet handed down for a juvenile lifer in Philadelphia. In an emotional resentencing hearing that began Tuesday, Martin's attorney, Louis Natali, argued that a sentence of 35 years to life, the deal offered to most of Philadelphia's 300 other juvenile lifers, was consistent with current state law. That would make Martin, who has already served 41 years, immediately eligible for parole.

In a letter read aloud in court by a District Attorney's Office staffer, Trettin's brother David said that would be an injustice.

"We live this nightmare every day. This is a life sentence for us. Andre Martin gave us this life sentence," he wrote, adding, "I just cannot accept saying it's OK to take another person's life, and that person goes free."

The case, high-profile in its time, involves a shooting of a white officer by a young black male, evoking issues of race and community-police relations that still reverberate through the city today.

Natali did not dispute the facts laid out by prosecutors: A few months before the crime, Martin had even told two police officers he planned to kill a cop in revenge for the death of a friend at the hands of an officer. He and two friends obtained a gun and were shooting it out a window. The friends testified in 1976 that they told him not to shoot at the police, but that after they left the room, he carried out the plan.

Both sides of the courtroom were packed. On the left, benches were filled with Trettin's friends and family: his children, Wendy, Tracey, and John; former and current police officers; and Mummers in the Quaker City String Band, whose membership included John and now includes John Jr. Across the aisle were Martin's extended family, childhood friends, and several of the other juvenile lifers who spent decades in prison alongside him, who describe him as a decent and kind person.

Assistant District Attorney Laurie Moore said the crime did not reflect the youthful impulsivity and susceptibility to peer pressure seen in many juvenile cases. "This is the antithesis" of what the Supreme Court decision stands for, "which is groupthink."

But Natali emphasized Martin's young age and chaotic childhood. Over the next two days, he intends to call witnesses who will speak to how Martin, now 57, has matured: corrections officers who trusted him enough to let him clean the warden's office, an expert psychologist who believes he's no danger to society, a fellow inmate whom Martin dissuaded from suicide, a brother who still looks to Martin as a role model, and an extended family that has remained close with him over four decades apart.

"He has accepted responsibility for what he's done," Natali said.

"That was 1976. It's been 41 years. What we want to talk about is what's happened in those 41 years."

Still, Trettin's family made it clear that 1976 feels like yesterday for them.

Trettin was 6-foot-8, a kidder, a gifted banjo player, a loving father. At holidays, he was the one shooting footage for home movies.

His older daughter, Tracey Hamilton, who was 6 when he died, said when she learned about Easter in school, she was overjoyed: She believed her father would rise again, and was crushed to learn he would not. His younger daughter, Wendy Callan, was just 4. She said that even to this day, at weddings, she breaks down during the father-daughter dance.

His wife, Claire, died of cancer in 2009. Her sister, Lorraine Crozier, said that after his death, "time stopped."

"She never remarried. No one could fill the hole in her heart," said Roseanne Gleeson, who was a juvenile aide officer at the time and became a close family friend. "The image of a 10-month-old little boy, leaning against his playpen waiting for his father to come home, and two little girls lying on the sofa will be forever imprinted in my mind. Unfortunately, he would never see his father again."

Throughout the morning, police officers stopped by, including now-Upper Darby Police Superintendent Michael Chitwood, who was a detective on the scene and a friend of Trettin's. Chitwood said that for those in service, the stakes in this case were extremely high:

"Whether it's 41 years ago or it's today, when one of your own is killed, it has a tremendous impact."