A clue on a rare cancer

Hospital's DNA offers lead on neuroblastoma's cause.

Using DNA samples donated by thousands of patients at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, doctors have found a lead in their hunt for the causes of neuroblastoma, the baffling cancer that killed Alex of Alex's Lemonade Stand at age 8.

"Until this study, we had no clue why one child gets this and not another," said the hospital's John Maris, who led the work and was Alex's oncologist.

Like Alex Scott, many children who get neuroblastoma are treated with a grueling course of chemotherapy, radiation and stem-cell transplants. "It's a very intensive treatment," Maris said, "and despite all that, it doesn't always work."

Maris' gene sleuthing took advantage of a $39 million effort at Children's Hospital to build the world's first extensive collection of DNA samples focusing on children. Researchers at the hospital have already tapped the collection to find new genetic insights into juvenile diabetes and autism and are taking on other diseases.

For neuroblastoma, Maris and colleagues were able to isolate variations in the DNA associated with the disease. He hopes this will lead to understanding how the disease arises and how it might be averted.

Neuroblastoma almost always strikes in infancy or early childhood. It is not a brain cancer, but it does attack the nervous system and usually starts with a tumor in a child's abdomen or chest. About half the cases are relatively benign and clear up on their own, the researchers say. In the other half, the disease is much more malignant, with a survival rate of 30 to 40 percent.

"What really gets you is a large number of patients who are very sick on presentation, and we make them even sicker with our therapies," said Kate Matthay, a researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, who studies the disease. "Perhaps these genes will show us another route."

Neuroblastoma and other cancers that strike children are thought to be triggered by leftover embryonic cells that retain some of their signals to grow and proliferate during development, Matthay said. Adult cancers more often stem from long-term wear and tear on cells, leading to garbled genetic instructions that signal out-of-control growth.

The goal in searching for genes associated with neuroblastoma is to better understand the root cause, not necessarily to single out those at high risk, Maris said. "The whole point is if we can understand the genetic basis of the disease, we can design therapies that are less toxic." He published his work in today's issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

For more than a decade, Maris has collected DNA from neuroblastoma patients. That was a slow process because the disease is rare, with just 650 to 700 diagnoses each year. He also collected DNA from the tumor cells, looking for clues to what had gone awry. A few years ago, scientists found several genetic errors in the more malignant tumors that were not present in the ones that cleared up.

For this more recent study, Maris attempted something that would have been impossible just a few years ago - comparing the entire genetic codes of 1,200 children with neuroblastoma and 2,000 cancer-free controls.

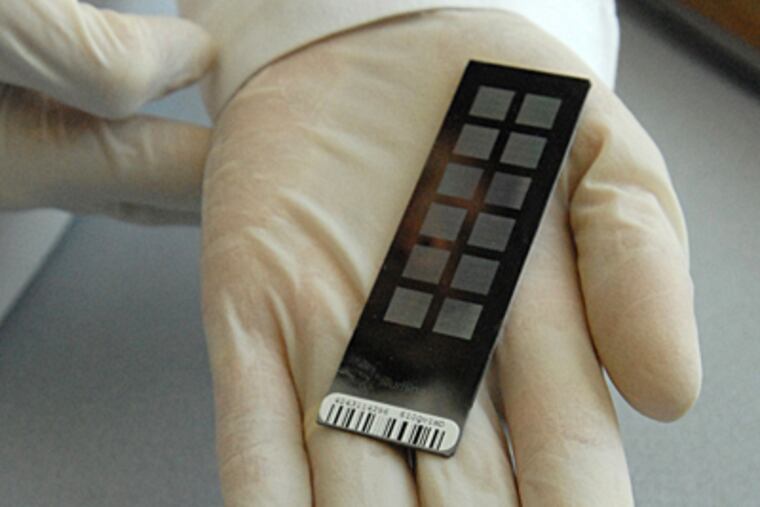

To carry off that ambitious plan, he said, he relied on the new research complex at Children's Hospital called the Center for Applied Genomics, established in 2006 with the aim of collecting a massive collection of children's DNA. "They were the key enabler," Maris said of the center and its leader, Hakon Hakonarson.

Hakonarson, who came to Children's Hospital from the Icelandic company deCODE Genetics, said the center had already collected more than 50,000 DNA samples from children and, in some cases, their parents. All patients at the hospital are invited to participate by giving blood whose DNA might be used to study not only childhood cancer but asthma, inflammatory bowel disease, diabetes and autism.

For the cancer study, Hakonarson said, "it was a perfect marriage in terms of John's expertise in the disease, his work getting the samples together, and from our end isolating the DNA, recruiting the proper controls, and analyzing the data."

The neuroblastoma study has not yet isolated a gene but simply a region on the DNA where alternative spellings show up more often in neuroblastoma patients than in the controls. All these spelling variations, or polymorphisms, cluster in the same region of Chromosome 6.

Maris said he was continuing to search for a gene - a stretch of code with specific biological instructions. That could lead him to a pathway, or series of biochemical steps that cause this cancer to start and spread.

Isolating the gene will not lead to a predictive test for neuroblastoma, because the spelling associated with the disease is common, while the cancer itself is rare. That means the vast majority of people with the alternative spelling will never get cancer. Matthay, the California researcher, said neuroblastoma was probably triggered by several genetic factors working together. Maris said he hoped continuing his analysis would reveal the other culprits.

Diane Blascovich, who lives in Queens, N.Y., hopes so, too. An advanced-stage neuroblastoma was diagnosed in her daughter Danielle in 2005 when the girl was just 5. Danielle endured seven rounds of chemotherapy, a bone-marrow transplant, and numerous courses of experimental drugs. "She had a rough time," Blascovich said.

Her daughter, now 7, is in remission. She has her energy back, and her long hair.

"She's in school full time, taking gymnastics, swim team, doing the normal things girls do," Blascovich said. But the danger is far from over, she said, and she applauds the families who have donated DNA to Maris and other Children's Hospital researchers.

"Naturally, I'd like to see other kids help out if it's going to help him find a cure."