A life of promise, frustration and tragedy

When Zal Chapgar took matters into his own hands, the questions only got harder.

The security camera tape shows a grainy, shadowy figure making his way through the main entrance of the Loews Philadelphia Hotel. He enters the elevators at 9:27 a.m. Dec. 1. On the 33d floor, the camera catches him again as he steps into the corridor, alone.

He is 23, heavily bearded and walks purposefully, with his hands in his pockets and his sneakers scuffing across the polished floors. The camera follows him until he disappears around the corner toward a conference room.

Two catering employees, setting up coffee for a breakfast meeting, would recall asking the young man if he needed any help.

"No, thanks," he told them. "I'm just going to take some photographs of the view from over there."

Then he headed toward the wall of windows looking east over the city, opened his backpack and took out a hammer.

For months he'd been straddling two worlds, separate realities. In one, he hung out with friends and his family and talked about science, philosophy and football.

In the other, seductive voices helped him visit another dimension. He'd always been spiritual, but he'd moved beyond mere faith in God. They were speaking directly to each other now.

He had tried so hard to keep the two realms apart. Maybe he didn't need to anymore.

When a mother boasts that her son is extraordinary, it's assumed that she's biased.

But that doesn't mean she's wrong.

"My Zal really was an exceptional boy," Kerban Chapgar says as she slices fresh ginger into black tea - "it's calming," she explains - and carries the mug downstairs to the den where her husband, Jay, kneels in front of the television.

The couple has lived in this Blue Bell split-level since 1985, when their daughter, Jasmine, was 5, and their son, Zal, 4 months old. This week, icicle lights zigzag along the eaves of nearly every house on the street. Plastic Santas bobble in the yards.

The Chapgars' property is bare this year. They've never been much into Christmas kitsch, but their current asceticism has more to do with the troubles that have kept them house-bound all month. It's all they can do to get through each day.

"I think this one is from first grade," says Jay, pulling the cassette from his treasury of memorabilia. Zal appears, standing before his classroom, wielding a wooden pointer like a scepter.

"This is what's true," he says with precocious confidence, and taps a picture of the entire pock-marked moon. "But this is what we see." Now he points to a slim crescent. "We are at an angle, so we only see a part of it."

His parents watch. Kerban's thick cloud of gray hair frames her fine features. At 60, she is a woman of strong opinions, disarming candor and profound emotion. Her tenderness is obvious, but you can imagine her fierceness as a mother. She has a master's degree in psychology and worked as a substitute teacher - until last fall, when her fight to save Zal and the ensuing battles with the insurance company, a college administration, and the mental-health system became a full-time job.

Her husband, 57, an architect in Pottstown, looks young despite his white beard and hair. He speaks with poetic gentility - yet if conversation drifts to rationalizations and blame, his composure may crack, hinting at the private turmoil beneath the surface.

They watch the video and talk about how proud they always were of this bright little boy. Listening now, they can't help reading double meanings into everything he said.

What is true? What did we see? Were we blinded by our angle?

They move on to the next tape: Zal in third grade, giving another presentation, this one about his family's heritage. He is taller now, poised. His parents, he explains, came from Mumbai, India, in their 20s. For a half-hour, he talks about architecture, poverty, food, art and culture. He explains the tenets of his Zoroastrian faith: "Good thoughts. Good words and good deeds. . . . To live a life without guilt, but don't hurt anybody."

Then he tells the history of his people. "There are only 180,000 Parsis left in the world," he says. "We're almost like an endangered species."

Jay sighs, pained. Under his breath, he comments, "And he didn't help."

Absence of malice

"He was very creative," says former classmate Ashley Palmer, who knew Zal from kindergarten at Stoney Creek Elementary in Blue Bell. "And he always had a different way of looking at things."

When you're a boy like Zal, only 5 and reading the newspaper every day, you're seen as a sage and a pariah, says Palmer, now 23 and a middle school teacher in Montgomery County. The backlash is only slightly less harsh in seventh grade, when you're so good with numbers that you take advanced math at the high school.

What sticks in Palmer's mind, however, is how graciously Zal handled the teasing. "He'd make a joke about it," she recalls. "I don't remember him ever getting angry or upset."

That absence of malice is one of the things that made Zal so likable. "He was himself," Palmer says, "and didn't seem to care what other people thought about him."

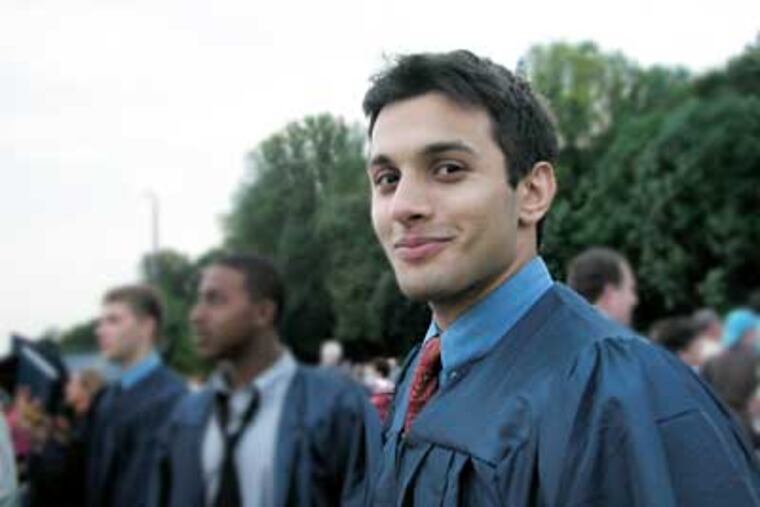

When he emerged from puberty, looking like the Entourage actor Adrian Grenier - thin, muscular, with mink-brown curls and sensitive eyes - he found himself suddenly popular. It was only then that he let on how hurt he had been by those early psychic blows.

"Some of the same people who weren't friendly with him or ignored him before suddenly treated him better," his sister Jasmine recalls. He resented the shallowness, the excessive value placed on physical beauty when he had been the same good person inside all along.

'A small tornado'

The third tape goes into the VCR. Zal is a junior at Wissahickon High School; it's just before the trouble starts. He has been named a National Merit Scholar and is being recognized by the school board.

In the video, his former middle school teacher, Sally Mills, steps to the microphone. "Zal," she says, "was one of the most memorable students I've ever had."

She talks about his mastery of mathematical formulas. His curiosity about the universe. His insight, imagination and sweetness. All wrapped, she says, in an exasperating package of unbridled energy. "He operated on 'Zal time,' " she says. He was "a small tornado with papers swirling around his sneakers."

During a lecture, she recalls, Zal would "pop in to say 'Hi!' from his parallel, alternative universe," then pose some astute question that would derail the class for the rest of the period.

"Zal may have been flaky," she says. "But what a mind. He was highly sensitive about the world and its injustices. He saw things that upset him and felt helpless to change them."

In the video, she imagines his future as a brilliant, disorganized professor of theoretical physics. And one more thing, she says; "He laughed at all of my jokes."

The school board laughs. Watching now, Kerban and Jay laugh, too. They see their son praise the district for giving him such a good education and talk about his hope to go to Annapolis or an Ivy League school.

Abruptly, Jay gets up, opens the sliding doors, steps onto the porch, trailed by the line about Zal's "alternative universe." That phrase, "he saw things that upset him and felt helpless to change them." And the vision of his son's future, now smashed and broken.

When Jay returns, he says he and his wife cope as well as they can. But the daily assault of regrets, what they could have done, what they should have done, can be unbearable.

"It's almost sadistic," he says.

Subtle changes

Looking back, Kerban and Jay see the first signs of Zal's illness in the spring of 2002.

One weekend, he went drinking with a group of kids and got into a car accident. That seemed to be the catalyst, they say. He became terribly depressed.

Over the summer, he worked as a lifeguard, but in September he began sleeping a lot. He refused to go to class.

"Every morning was a huge fight trying to get him to school," Jasmine recalls. "Zal just always won." His parents didn't know what to do.

Maybe it should have been obvious that Zal needed psychological help, but it wasn't as if a neon sign flashed a warning. The changes were so subtle, so incremental, that they were hard to measure. It was like watching a child grow.

By the end of senior year, he had missed more than 40 days of school. His grades had faltered, and he had applied to only Bloomsburg University and one other college.

Lately, his parents spend sleepless nights retracing their missteps.

From the tenderest age, their son's quicksilver mind, his abstract thoughts and esoteric interests had led him to the boundaries of "normal." One teacher told them Zal seemed lonely.

"Intellect is considered a gift, but is it a curse?" Jay wondered in an e-mail. "He must have felt so . . . alone . . . interacting with his peers who would not or could not know him as he truly was."

Rather than pressuring Zal to achieve, Jay wishes he had been more compassionate: "I feel such wrenching regret and sorrow as I write this, and I know I will live with this forever."

The reality, says Dr. Ken Duckworth, medical director of the National Alliance on Mental Illness, is that most families need time to identify their child's problems.

"I encourage parents to be gentle with themselves," he says. "To have a child with mental illness presents an extraordinarily complex series of challenges. Very few parents went to grad school to learn how to manage this."

Like the Chapgars, parents tend to interpret early signs of trouble as a phase, something that can be fixed with a little more time, a little more support.

"I think that's very human," says Duckworth, an assistant professor at Harvard University Medical School. "They're trying to figure out what narrative makes sense. If their kid is in a phase. Are they sticking it to their parents? Or having difficulties in school? Was it because they broke up with that girl?"

The one story every parent finds hard to believe is that their child has a mental illness. Support groups like the ones the National Alliance on Mental Illness runs help families learn to cope, Duckworth says. "But you have to realize - this is a club no one wants to join."

And frankly, he says, the American mental-health system is "not great."

Zal always had more steam at the beginning of a project than at the end. So his parents were disappointed, but not surprised, when he didn't finish the last few requirements to become an Eagle Scout.

He missed a few class assignments, and they worried. Teachers and counselors reached out to him.

"There are lots of students who turn off and don't do their work, particularly after December, when their college apps are in," says Barbara Speece, his Advanced Placement English teacher. "It wasn't totally unusual that somebody did what Zal did, although his case was a little more extreme."

In his spare time, Zal would still beat his father at chess, devour Scientific American, and rip through books by the physicist Stephen Hawking.

He still sang beautifully, played the piano and guitar, wrote poetry. Picking up clay for the first time, he molded a perfect torso. He seemed to master everything he touched. Maybe he just had senioritis. If he were really in trouble, how could he have nailed the SATs and aced his AP exams?

And through it all, his performance on the wrestling team reassured them.

"During his senior year, he ended up being the Section 3 champion," recalls Jeff Madden, Zal's coach since ninth grade.

Zal was never a superb athlete, Madden says. Because stronger wrestlers filled all the spots in the lower weight classes, Zal was bumped up to a heavyweight. At 5-foot-11 and 184 pounds, he found himself on the mat with boys 100 pounds heavier.

He won, says Madden, by outsmarting them: "He'd allow these guys to tire themselves out, and not give up points early. That was not easy to do."

Even when Zal began having difficulty getting out of bed, he would still wake at 5:30 a.m. for wrestling practices because the team depended on him.

As a result, Madden says, he had no clue that anything was wrong: "He was always in a good mood." And he seemed to be sustaining his well-earned rep for being as scatterbrained as he was school-smart.

The coach remembers kidding with him.

"I once asked the team, 'Who's the smartest guy in the room?' "

Zal's hand shot up.

"OK," Madden said. "I'm going to ask you a question."

Zal prepared himself for something about black holes or sub-atomic particles. Instead, Madden threw him a real puzzler.

"What time is the bus leaving?"

"Aaawww," Zal groaned.

Stumped.

Devastating accident

In the fall of 2003, Zal entered Bloomsburg with 26 Advanced Placement credits and a passion for astrophysics. He spent the next five years in and out of school.

"Everyone knew Zal," says Greg McCleary, a Bloomsburg classmate and later his roommate. "He was very social. He never wanted the night to end."

In the spring of 2006, he started doing poorly in his classes and would disappear for days, then return having won and immediately lost impressive amounts of cash playing poker in Atlantic City.

He dropped out for a semester, then re-enrolled.

"He told us he had learned from his mistakes," Kerban says, "and was going to turn things around." At first, he was back on track. The skies had cleared. He focused on his schoolwork and got A's.

Zal had no steady girlfriends, but he and a friend, Meghan O'Riordan, were spending a lot of time together, and were close.

On Feb. 4, 2007, she was killed in a car accident.

"He was devastated," says Jay. Overcome by grief, Zal fell into a deep depression.

In September, Zal felt well enough to return again to Bloomsburg. Perhaps the worst was behind him.

It wasn't. His first week back at school, he began hearing voices.

By the time he withdrew for good in April, he had not declared a major, and many of his friends and classmates had long since graduated.

Misunderstood diseases

Although an estimated 5.7 million Americans have bipolar disorder and two million live with schizophrenia, these diseases remain widely misunderstood.

Studies repeatedly have found that the great majority of people with mental illness are not violent.

Zal believed that all living things have a soul. He would protect even spiders, ants and mice. Politically, he was a pacifist. In his high school yearbook he quoted Gandhi. Even in his darkest moments, he remained a gentle man.

But public misconceptions are hard to shake.

In April 2007, a disturbed student killed 33 people at Virginia Tech University.

The tragedy reinforced the association between mental illness and violence, and so worsened the stigma that prevents patients, and their families, from seeking treatment early, when it can be most effective.

The stigma also drives people into isolation so they feel like exiles in their own communities.

Once the Chapgars began talking about Zal's problems, they were surprised to learn how many people they knew were quietly struggling with similar issues. And in the search for professional help, how many others, like them, felt blocked at every turn.

Insurance companies had unworkable limits on what they would and wouldn't pay for. A fortress of rules and regulations kept the university and health professionals from sharing information because Zal was over 18.

Was Zal making appointments with the counseling center? Seeing his psychiatrist? Going to class? Taking his medication? How was he? The Chapgars could not find out.

How could it be that their son, financially dependent on them and clearly not rational, retained total control over decisions affecting his very survival?

"There were very helpful people along the way," Kerban says. But mostly, she and Jay were told "No" or "We can't tell you" or "I'm sorry."

The soul-searching (and finger-pointing) that followed Virginia Tech led to an important loosening in the rules that have prevented schools from sharing personal information about students. Administrators have more latitude now in deciding when to override a student's right to privacy. Ironically, the change, intended to protect society from these rare acts of violence, actually addressed the widespread need for young people with mental illness to get help sooner.

The change went into effect Dec. 9. It came too late for Zal and his family.

Hard to stay angry

Zal's friends loved him, but say the fervor of his beliefs and the depth of his convictions could be exhausting. If he fell for a girl, he fell hard. Trying to persuade you of the omnipresence of God, that every living thing had a soul, he would go on half the night until you agreed.

"Zal didn't draw the line," McCleary says. "He didn't see the line." If he felt the need to talk or ask a favor, he would knock on a stranger's door at any time of night. On one hand, his friends say, Zal could be rude and inconsiderate. But he was such a sweet guy and seemed so unaware he was doing anything wrong that it was hard to stay angry with him.

So McCleary and his friend James Rose agreed to rent an apartment with Zal. They moved in over Labor Day weekend 2007.

Within a week, whatever doubt Zal's roommates had about his mental stability vanished. Zal began hearing voices and would argue with invisible bullies, shouting, "I'm not fat!" or "That's not true!"

His friends tried to get him help, but Zal refused. He told them he didn't have a problem, other than making everyone understand that nothing was wrong: What he was hearing and seeing was real.

Eventually, they managed to get him to an emergency room, where he was given a sedative, then released.

Over the next month, Zal's friends and parents tried to work with the school's counseling center. They repeatedly called a mental-health-crisis hotline. Crisis workers came to his apartment to persuade him to come with them to seek help. Hours later, they would leave, defeated. Unless he was a danger to himself or others, they could not force him into treatment.

University administrators got involved. His parents visited again and again.

His condition worsened. He stopped going to class. He was hospitalized twice. The second time, after a two-week stay, his sister and a friend drove up in mid-November to bring him home.

The Chapgars were shocked when they saw the date the hospital had arranged for Zal's first follow-up appointment with a psychiatrist.

It was not for an entire month.

Although the voices persisted, Zal desperately wanted to resume a healthy life. Over winter break, he and his psychiatrist agreed that he should return to Bloomsburg in January. His family didn't think he was ready. But he told them he wanted to get back to normal.

He couldn't.

A suspended life

Jasmine is in her bedroom, watching videos of Zal. Here he is dancing at a 2005 wedding. Here he is playing basketball. And here, in a garden with one of his young cousins, he marches in loops and circles as she giggles, delighted.

Here he is at Jasmine's birthday party, talking about neutrinos and background radiation. "The more we learn," he says, "the more we learn what we don't know."

These days Jasmine is struggling. For the last 18 months, she had suspended her life trying to save his.

She looks barely old enough to drive, but she's actually 29, with long, dark hair and a tenacity at odds with her physical delicacy. An honors graduate of Rutgers University, she designs animated games for an educational Web site.

She loved her brother with intense devotion.

"He had so much hope for the world," she says.

During her numerous visits to him during his last year at Bloomsburg, he told her he felt alone. That he was living a double life. He would will himself to inhabit his friends' world, and kept his thoughts and the voices to himself so he didn't scare them.

But increasingly, his alternative universe felt more comfortable. There he could talk to God and his friend who had died in the car crash.

"He would cry," Jasmine says. "He said he couldn't talk to anyone truthfully. He had to suppress a lot. He was very worried about how he would ever fall in love with someone. 'How could a girl love me if she thinks I'm crazy?' "

He believed he could fly, but knew that admitting it openly could land him back in the hospital. And he loathed hospitals.

The welcoming lobbies belied barren patient quarters. He'd be kept only long enough to get through a crisis, and then he was on his own. Group therapy sessions were unhelpful. And although most staffers and doctors were caring, the family heard others snap at patients, "Get out of here!" or "Go back to your room!"

Over the last year, his parents say, doctors seemed to be flailing, trying to find something, anything, that would work. Zal was taking a mood stabilizer and medicine for attention-deficit disorder, and he received weekly shots of an antipsychotic. The regimen wasn't effective.

In January, he began talking about how his death would heal the world. Jasmine worried constantly. She sometimes worked from home to keep an eye on him. And when she left, she always made sure they had a plan for that evening.

"Remember," she'd say, "we're going to play Mario Kart tonight."

She taped a list above the couch in the den, where he was spending 20 hours a day. "Things we still have to do together," she wrote. "Go to Dorney Park. . . . Go to India. . . . Write a song/music together. Many more things!!"

She gave him another list, "Things that are nice," to read when he was feeling sad. "Music. Hummus. Hot showers. Your jokes . . . Ants that need saving . . . your sister who adores you."

More research needed

"Approximately 70 percent of people who are suffering with significant symptoms are not getting help," says Marc Rothman, chief medical officer of Friends Hospital in Philadelphia.

More research into brain function and dysfunction is needed, Rothman says. Good medications and effective treatments are available, but first, you have to figure out how to negotiate the current mental health care system, which he describes as byzantine.

Insurance, so often tied to employment, is out of reach for many people with mental illness, who have trouble finding and holding down jobs, he says.

Considering the obstacles, one doctor they worked with said, the Chapgars did a remarkable job, although they feel they failed Zal.

"To this day," Jay says, "we don't know the diagnosis."

No blood tests identify mental illnesses. No simple treatment cures them. Symptoms intersect and create a muddle, Rothman says. Bipolar disorder, he explains, is a mood problem, which can distort thinking and create delusions. Schizophrenia is a thinking disorder, which can trigger extreme moods. Throw substance abuse into the mix - about 50 percent of the mentally ill abuse drugs trying to self-medicate - and the muddle can become impenetrable.

Not the person they knew

In August, Zal spent a week with friends in Seaside Heights, N.J. He could still make them laugh and goofed around, picking up one of the girls and tossing her in the surf. But he was no longer the person they once knew. He spent hours staring at the stars, talking about UFOs, and relating his conversations with God.

He continued to see a psychiatrist once a week, and in September appeared to be doing better. Jasmine helped him prepare his resume. He applied for, and was trained in, a job selling Cutco knives.

But just before he started the job, he nearly overdosed on cough syrup. He denied that he meant to do himself any harm. His explanation was plausible; he was just self-medicating. But the incident was terrifying, nonetheless.

Jasmine rode beside him in the ambulance to the hospital. The EMT's mother had killed herself, he told Zal. He wanted Zal to understand how badly her suicide had affected him.

"Look at you," the EMT said. "Your sister is here. She cares about you. And your parents. Don't you want to live for them?"

The EMT was fighting back tears. Zal and Jasmine were both crying.

He promised his sister he wouldn't kill himself.

That was Sept. 10.

An unexpected trip

Zal spent most of the next six weeks at home, sleeping. In early November, he seemed to have found peace. He began giving everyone prolonged hugs and saying he loved them. But he had always been affectionate, so they shrugged off any suspicion that something was awry.

On Thanksgiving, the family went to a cousin's house, where Zal watched the Eagles and talked about football.

On Sunday, he announced that he would go into the city the next day to take part in a market-research survey. The idea came as a surprise. Jasmine had signed him up with a firm years before as a way to earn pocket change, although he had never followed through.

Why now? they wondered. He had not gone anywhere by himself in months. When Zal asked Jay to take him to the train station to catch the 7:33 a.m. to Center City, they all asked, are you sure?

His mother was worried. Jasmine tried to persuade him not to go. "There were a million scenarios I imagined." But couldn't getting out of the house be a good sign? She tried to be optimistic. He had told Kerban, "I've been so happy this week."

Monday, Dec. 1, Jay went down to wake Zal, but found him up and dressed. Jasmine was still asleep. He ran to her room and gave her an unusually long hug.

"You are just extra cuddly today," he explained, then he told her he loved her and left.

Jay drove. How nice it was to be up early in the morning, they agreed. Jay walked Zal onto the platform. Gave him $20 for the train and an extra pen. "I always carry an extra pen in my pocket. But he said he didn't think he needed it."

Jay told Zal he'd noticed a positive change in him and was really proud. Zal said, "God has been helping me."

At 9:38 a.m., Zal, on the 33d floor, checked his messages. There were none. Maybe he thought it was a sign.

After she got up, Jasmine texted Zal and later called the marketing group to see when the meeting would end. There was no meeting, they said.

At 10, Jay and a cousin began calling him.

But Zal had already pulled out the hammer. He shattered one of the conference room windows. Then he climbed onto the chest-high ledge, where the hammer was later found.

To the left he could see the Aramark building. The gray Delaware River, like unraveled yarn, lay straight ahead, and beyond it New Jersey. To the right, moss blanketed the tar roof of a commercial building.

Below him, the cars and buses looked so small, like toys, with miniature people going about their morning missions with purpose. Zal had one of his own.

Below, a woman screamed as a dark mass hurtled from the sky and crashed into the sidewalk in front of her.

A hotel employee covered the crumpled body with a white sheet, but a clenched fist and twisted foot were still visible on the concrete. For two hours, while police investigated, he lay there, an anonymous victim. Passersby wondered what he must have been thinking. They stared but kept their distance.

One man stopped to take a photo with his cell phone. "Yo!" came an angry voice from the crowd. "Show some respect, man!"

At noon, Jay called again. There was no answer, but he remembered what Zal's friends had told him. "He never picks up, so you have to call and call and call."

At 12:07 p.m., a woman answered. She said she was the coroner. Beside her lay the remains of a young man who was tired and lonely and believed he could fly.

For More Information

The National Alliance on Mental Illness provides information and organizes support groups for families of people with mental illness. To contact:

717-238-1514 or

800-223-0500.

Or nami-pa@nami.org.

Web site: namipa.nami.org.

Information Helpline: 800-950-6264.

NARSAD (previously known as the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression) is a private, nonprofit group that raises money for research into mental illness. To request educational materials or information, call:

NARSAD at 800-829-8289 or e-mail info@narsad.org.

To make a contribution:

60 Cutter Mill Rd., Suite 404

Great Neck, N.Y. 11021.

EndText