The sad life of Margaret Jones

For two days, Margaret Jones lay at the top of a dank SEPTA stairwell near Eighth and Filbert Streets. Subway commuters by the scores passed the 61-year-old woman, covered with three dirty blankets, her head propped on a plastic bag, a concern to no one but the other homeless regulars who hung out there.

For two days, Margaret Jones lay at the top of a dank SEPTA stairwell near Eighth and Filbert Streets.

Subway commuters by the scores passed the 61-year-old woman, covered with three dirty blankets, her head propped on a plastic bag, a concern to no one but the other homeless regulars who hung out there.

They worried about Margaret, schizophrenic and diabetic. She wheezed heavily and, in her hot-pink cropped pants, was not dressed for the 25-degree January night.

"Miss Margaret, let me take you to the hospital," implored Tom Papineau, a middle-age homeless man.

"No, no," Margaret insisted. "Not the hospital."

She refused to budge.

Tom left the stairwell at the old Lit Bros. side foyer to get food. When he returned around 10, a homeless couple was fussing over Margaret. She was still on the floor, but her eyes were blank.

By the time a SEPTA officer bounded up the steps to help, her face had drained from tawny to gray. Kneeling beside her, he lifted her limp wrist, searching for a pulse.

Someone at the city morgue found a phone number in the pocket of Margaret's navy-blue jacket, and the next morning - Jan. 20, Inauguration Day - called it.

The number belonged to Inga Faye Jones, 41, a counselor who lived in Germantown.

"Is your mother Margaret Jones?"

"Yes," Inga answered. "Is she dead?"

"Yes."

Inga screamed.

In New York, Ira Mia Jones, 42, a Harvard-educated urban designer, was leaving a subway station when her sister called with the news.

Stricken, Ira fell backward, into the arms of a stranger.

Descent into illness

Mental illness is an odyssey that, at its saddest, ends on the streets.

Margaret Jones had daughters who, even before they were teenagers, were trying to save her.

She had city caseworkers and doctors at almost every major hospital in Philadelphia involved in her care, on and off, for the last decade.

In her final days, she had police officers and homeless outreach teams looking for her.

And yet Margaret died - of natural causes exacerbated by hypothermia - on an icy night in a subway stairwell, a block from a shelter.

On Thursday, the city began an "internal review" of her case, which could conclude midmonth.

"We really want to understand what happened and if there was anything we could have done differently for this woman," said Arthur C. Evans, director of the Department of Behavioral Health/Mental Retardation Services, which handles mental-health care for low-income residents.

Margaret Jones, however, was no anomaly.

This winter, by city estimates, at least 300 people were encamped on the streets. Just since the start of January, 20 of them perished. She was No. 5.

For most of her adult life, Margaret had walked away from help. She wandered the country, taking off for Boston, Baltimore, New York, Georgia, South Carolina, Texas. During her "walkabouts," she survived on the streets or in shelters until someone - usually police - forced her to a hospital. From there, she might land in a residence for the mentally ill.

Margaret would stay for weeks, months, even years - but never long enough.

Last year, as her roaming grew more frequent, her daughters and city caseworkers agreed that Margaret needed to be in a long-term residence with the most stringent supervision.

In the last two decades, big psychiatric institutions such as Philadelphia State Hospital - Byberry, a name synonymous with abuse and neglect - have been replaced by a network of housing options. But for the type of restrictive facility Margaret needed, the city had only 140 beds operated by seven nonprofit agencies.

The waiting list, her family was told, was a few years long.

On Jan. 5, at the end of six months in the psychiatric unit of Albert Einstein Medical Center in the city's Logan section, Margaret was discharged to a Germantown personal-care home, essentially an 80-bed boardinghouse. It had minimal services for the mentally disabled, such as making sure they took their medication and kept treatment appointments. But residents were free to come and go.

On her first morning there, Margaret went out for cigarettes with $10 in her pocket.

She never returned.

A spokeswoman for Einstein, Judy Horwitz, declined to comment on Margaret's case, citing privacy. But according to Margaret's daughters, the hospital team believed their mother was stable, eager to leave, and willing to try a personal-care home.

Ira, out of the country on a two-week trip, was not consulted about Margaret's release. Inga went along with the hospital's decision.

She did it, she said, because her mother "wanted so badly to be free."

A flamboyant youth

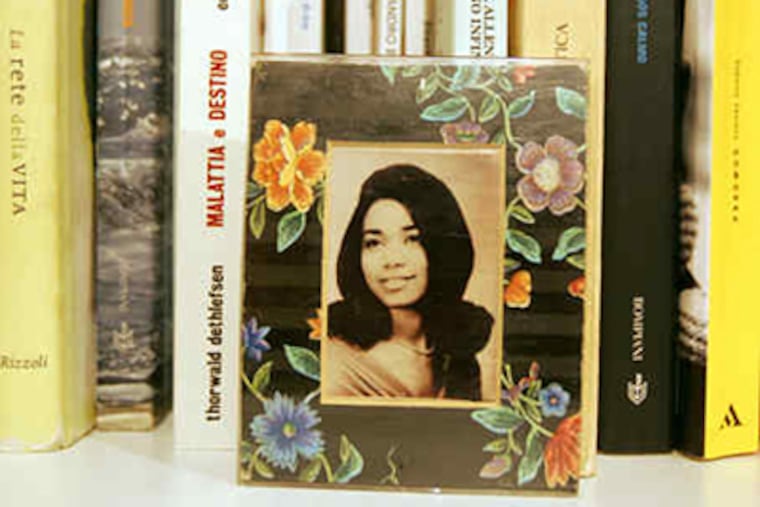

Margaret Jones had salt-and-pepper hair that stood straight up and a rough-hewn smoker's voice from a two-pack-a-day habit.

But in her youth, she had such striking looks and style that old friends still swoon at the memory of her sashaying down the sidewalk in South Philadelphia.

One of four children of a homemaker and a shipyard worker, Margaret had a flair for fashion. In the early 1960s, she left every morning for South Philadelphia High School in the dowdy skirts that her Baptist parents approved - then changed into flamboyant outfits that she secretly made herself.

Once, she showed up in a blue chiffon dress, blue stockings, blue shoes, and thick blue eye shadow. Another time, she wore a kimono-style dress with black slippers.

A good dancer, Margaret appeared a couple of times on American Bandstand. The show was notorious for excluding African American teens, but with her flipped shoulder-length hair and light skin, she could "blend" with whites, said Rita Wheelings, a friend from South Philadelphia. The young Margaret "put you in mind of Tammi Terrell," the Motown singer, also Philadelphia-born.

While in high school, Margaret caught the eye of James Edward Jones, a lineman for the electric company. They eloped at 19, to the lasting disapproval of her parents, who felt she had married beneath her.

For two years, Margaret took general classes at Temple University while working. She was a salesclerk for Fisher Bruce & Co., an upper-crust china shop on Market Street, and a floor model at stores like posh Nan Duskin. She drove a hearse, retrieving bodies for a funeral home, and even thought about being a mortician, so intrigued was she with the idea of dressing people and making up their faces.

But what Margaret quickly became was a mother, with two daughters born one year and four days apart.

Like many of his generation, James went off to Vietnam to fight. About two years later, he returned a changed man. Their relationship deteriorated, and Margaret took her girls to live with her sister in Detroit.

James tooled around South Philadelphia in a red Cadillac, wearing a big hat over a bigger Afro. On Oct. 8, 1973, while driving an acquaintance to West Philadelphia, James was shot and killed.

Margaret returned to Philadelphia, where her behavior turned erratic. "She was in tears all the time," Ira said. "James plagued her mind."

Depressed and prone to angry fits, Margaret was unable to sleep, tormented by voices who said her daughters were being beaten and bound.

After the girls began missing school, the city's Department of Human Services removed Ira, 6, and Inga, 5, from Margaret's custody. They were eventually placed in St. Joseph Hall for Girls in Germantown, a Catholic orphanage run by the Daughters of Charity.

Margaret visited, on good days arriving prim and polished in a demure suit. With medication, she could hold a job. She brought the girls armloads of gifts: porcelain dolls, puzzles, chemistry sets, pricey clothes like the matching white rabbit-fur coats.

On bad days, Margaret frightened even the orphanage staff, appearing on the steps wild-eyed and unwashed, lugging bags of her belongings. Some wanted to shield Ira and Inga from her, but activities director Harriett Atkerson, who befriended the girls, objected. "I told them the kids didn't care what shape she was in," she recalled. "They loved her."

Margaret couldn't take care of her daughters, but she didn't want anyone else raising them, either. She was livid when Inga, at 11, was sent to a foster family. "She wanted me to know that no one else was my mother," said Inga, who reluctantly returned to the orphanage.

Margaret had an even fiercer gravitational pull on Ira. While the staff found the girls to be uncommonly cheerful, Ira, below the surface, was wrestling with anger. At 12, she taught a younger girl how to start a fire in the orphanage - a stunt that put her in the Youth Detention Center for 18 months. Released to a halfway house, she fled in search of Margaret.

"I thought I could take care of her," Ira said. "I thought if I was a better daughter, she'd get better."

Margaret was working as a cleaning lady and living in run-down, unfurnished house in West Philadelphia. She bought Ira a cot, lamp, and tiny TV, and for a while life was blissful.

Mother and daughter stayed up all night, laughing, dancing, and singing pop tunes like "Ain't No Stopping Us Now." Margaret slept on the floor in her clothes, a habit from the streets. Ira would lie next to her, the two of them making shadow figures with their hands on the walls.

But over time, Ira began to notice signs of trouble. Margaret wasn't sleeping. She warned Ira, "Everyone is out to get us!" She scratched her wrists until they bled.

One day, Ira took her mother by cab to Misericordia Hospital in West Philadelphia and, after pleading with the doctors, left her at the emergency room.

High school interludes

High school was a rare time of stability for the girls.

Still wards of the state, they were placed in a Catholic group home in Ardmore. Inga went to West Catholic High School; Ira had a scholarship to Merion Mercy Academy in Merion Station.

The transition from a tumbledown home with her mother to a Main Line school with college-bound girls in uniform was jarring for Ira. "They had plans," she said. "I had nothing."

Few of Ira's classmates knew her background. "She was so upbeat," said Judy Straub, a friend from Merion Mercy. "She didn't want to dwell on it."

Once, Ira was on campus when she heard someone shouting her name from afar.

It was a disheveled Margaret, wearing a winter jacket despite the warm weather and hauling her dirty bags.

A guard raised his arms to stop Ira. "Don't go near her," he said. "I've called the cops."

"Please don't arrest her," Ira told him sheepishly. "That's my mom."

After that, students started dropping checks in Ira's locker. "I was embarrassed," she recounted. "I also thought, I always will defend my mom."

A home, for a time

Margaret and her mother, Ira Mae Berry, had been estranged ever since she eloped with James. But when the girls graduated from high school, Ira Mae bought them a small brick rowhouse in the 1900 block of South 19th Street so the three could live together.

The girls became Margaret's caretakers. "I was the mom more than she was," Inga said. "I wasn't angry at her, but I was angry at the situation."

Inga worked variously as a bank teller, customer service representative, post office clerk, and counselor at a mental-health residence.

Ira enrolled at Temple University in architecture, paying for the $20,000 degree in part by selling gloves at Strawbridge's.

As a student, Ira stood out. Creative and skilled, she understood instinctively that architecture was not only about a building's look but its place within a community. And she understood something else: "that whatever she wanted, she'd have to make it happen," said Rebecca Williamson, one of her professors.

During this time, Margaret was being treated for her schizophrenia and paranoia through city-supported treatment centers. Medicaid covered hospital costs.

If she listened to the doctors, she could hold down a menial job. But for reasons no one understood, she would stop taking her medicine and act out. She picked through trash for food. She cranked up the heat to stifling. She called 911 every 20 minutes. She put out her cigarettes on the mattress.

"She challenged my compassion," Ira conceded. "You can hate a person like this."

Once, Ira grew so impatient that she smacked her mother in the face. "She was so surprised. I was so surprised," Ira said. "I told her, 'I disrespected you, and that's not the person I am. I'll prove it to you.' "

But Margaret's wanderlust was taking her farther and farther from the house on 19th Street. "It was like a jail to her," Inga said.

In 1993, Margaret used her government disability check to buy a bus ticket to Dallas. Police there found her roaming the streets, full of fury and fear, and took her to a hospital.

Deemed a threat to herself - the legal standard for involuntary commitment - she was put in a state hospital set on acres of green fields in Terrell, Texas.

Ira scraped together enough money to visit her mother twice during her two-year stay there. In the wide-open spaces, Margaret was happy. Until she suddenly wasn't.

Back in Philadelphia, the pattern repeated.

"She'd say, 'Ira, I'm going out for cigarettes.' A week, three weeks, a month later, she would call me and a doctor or nurse would get on the phone and say, 'Your mother's here,' " Ira recalled.

In 1996, Margaret ended up in Manhattan, where police took her to St. Vincent's Hospital. After four months, her mental state had improved enough for Ira to pick her up.

In 1997, Margaret took a bus to Boston and was committed to a state psychiatric hospital for the next three years. At Lemuel Shattuck Hospital, she seemed content.

Ira visited often, one day taking Margaret out to Cambridge. At Harvard Square, Ira told her, "Mom, wait here. I want to go look at a famous building" - a visual-arts center designed by Le Corbusier.

When Ira returned, she found her mother panhandling and boasting to passersby, "My daughter's going to go to Harvard."

In late 1998, Ira's visits came to an abrupt halt.

On a moonlit night, she was riding on the back of her boyfriend's motorcycle when they hit a car head-on on West River Drive. Ira broke her back and a leg.

In a body cast for eight months, she recuperated in the home of her orphanage friend Harriett Atkerson. In time, she used a wheelchair to resume classes at Temple, and graduated in 1999.

Ira's friends urged her to accept a scholarship for graduate school at the University of Illinois. They worried that her home life "was stalling her," said Oktavia Cherry, who had worked with her behind a counter at Strawbridge's.

Having come so close to death, Ira decided to go.

But that meant that the burden of caring for Margaret, back home from Boston, would fall on Inga's shoulders.

"I never had a chance to leave," Inga said. "I felt destined to take care of her."

Inga had her own mental-health issues. In 2000, she gave birth prematurely to a daughter who died at 38 days. Bipolar, she struggled with depression.

Margaret did not make it easier.

"I was working as a crossing guard," Inga said. "And people would tell me, 'I saw your mother sleeping in the Citizens Bank ATM lobby on Broad Street.' Or, 'I saw your mother in the yard of South Philly High.' . . . It was very scary for me."

As she moved like a pinball among hospitals, case managers for the city Department of Behavioral Health/Mental Retardation Services tried to find suitable housing. In 2003, they placed her in Homeward Bound, a campus-style residence in East Oak Lane for 20 homeless people with mental illness.

Those were rare "golden years" for Margaret, Ira said. Stable and content with her environs, she left only for an occasional panhandling trip to Center City. Mostly, she loved sitting in the lounge and loudly bragging about her daughter the architect.

Ira got her master's at Illinois and went on to teach at Columbia University. In New York, she met and married an Italian architect, Alessandro Cimini. In 2004, she entered the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

With even more to crow about, Margaret flaunted her "Harvard Mom" T-shirt. But when Ira graduated in 2006, she wasn't there.

Margaret was hospitalized, after pleading with a police officer to capture Osama bin Laden. She was sure the terrorist was hiding at St. Agnes Medical Center in South Philadelphia.

Compelled to stray

Ira and Inga were already worn down by a lifetime of chasing their mother. And the older she got, the more impossible it was to hold her.

In spring 2007, during an ambulance transfer from a hospital to a treatment residence, the attendant turned his back. She walked off.

Margaret eventually returned but, within a year, took off for Baltimore. There, however, her Medicaid insurance for services in Pennsylvania did not apply.

Sent back to Philadelphia last May, she was immediately committed to the Belmont Center for Comprehensive Treatment, a psychiatric facility affiliated with Einstein, and then to Einstein's hospital.

There she waited for a spot in a long-term residence with 24-hour supervision, comparable to the restrictions at a state hospital.

She was still waiting when Thanksgiving rolled around. Ira and Inga tried to cheer their mother at Einstein by bringing her a home-cooked meal of turkey, fried chicken, sweet potatoes, collard greens, and pies.

But Margaret was withdrawn. During dinner, she whispered to Inga, "I don't belong here."

Her hospital team agreed and discharged her Jan. 5 to a personal-care home, not to the secure facility that her daughters had hoped for.

At 6:29 p.m. Jan. 7, the operators of Kaysim-Court Manor in Germantown filed a missing-person report, according to police records.

Ira got word of Margaret's disappearance just as she returned from a Christmas trip to Italy to visit her in-laws.

"I've got bad news," Ira said she had been told by Todd Weinstein, her mother's social worker at Einstein.

"Let me come down to help," Ira insisted.

"No, we have it covered," she said Todd had told her. "Everyone's looking."

Ira hung up and repeated a prayer the orphanage nuns taught her.

Dear St. Anthony, please come around. Something's lost and must be found.

On Jan. 9, a SEPTA police officer recognized Margaret from the missing-person report. She was wandering the warren of halls and stairwells at the Market Street East station.

A homeless outreach team took her to the Hall-Mercer mental-health-crisis center at Pennsylvania Hospital.

She walked out.

Inga drove around the city, looking for Margaret at LOVE Park and City Hall, South Philly High and Citizens Bank on Broad Street.

She did not look in the stairwell near Eighth and Filbert.

The funeral

Margaret Jones was laid out in a pink-and-gray casket at the Slater Funeral Home in South Philadelphia, in a room filled with the tropical scent of white and pink lilies.

She was dressed in a long, beaded ivory gown. Her lips were painted red, her hair tucked under a wig. In her hands were rosary beads, placed there by Ira.

About 40 people sat before the casket. Margaret's parents were dead, but a sister and a brother paid their respects. So did relatives of her late husband, James, and a contingent of Ira's coworkers at a Harlem development nonprofit.

Ira spoke, though not of the pain she felt at the way Margaret died. It was a far cry from what she had imagined, that at the end she would be there to hold her hand.

"My mom had a troubled mind," Ira told the mourners. "But because of my relationship with her, it made me a better person."

After the service, a police-officer friend of Ira's turned on his patrol car's flashing lights and led the procession to the city limits. Seven cars continued on to Mount Zion Cemetery in Collingdale, Delaware County.

There Margaret was buried beside James, to wander no more.