No peace on how Jim Thorpe rests

His family wants an Indian burial outside Pa. It plans to sue in Phila.

JIM THORPE, Pa. - It took 30 years of requesting, cajoling, demanding, and threatening, but in 1983 the family of Jim Thorpe was finally given back the two gold medals he won at the 1912 Olympic Games. Since then, it has been trying to get something else back - his body.

For 25 years, family members have been working to persuade the people of this Carbon County borough to return the famous American Indian athlete's remains to a burial ground near Shawnee, Okla., where his father and many other relatives are buried. But the pleas have gone unheeded, and now the family plans to sue in U.S. District Court in Philadelphia.

"According to Sac and Fox tradition, Dad's soul will never be at peace until his body is laid to rest, after an appropriate ceremony, back here in his home," said Jack Thorpe, the youngest son. "Until then, his soul is doomed to wander. We must have him back."

"This is incredible," Mayor Ronald Confer said. "It's been more than 50 years. It's too late. No one in this town is going to be for that."

Thus, one of the most bizarre of all American sports stories appears headed for a showdown.

It's a complicated story, and one thing needs to be perfectly clear: Jim Thorpe, the Sac and Fox Indian who won fame but no fortune as an athlete, never set foot in Jim Thorpe, this charming, picturesque town in northeastern Pennsylvania. Thorpe had been dead for 11 months when his third wife brought his body to the town in 1954 and offered to make it his final resting place if the community changed its name in his honor.

The people of the town, then named Mauch Chunk, voted to accept the offer after community leaders promised extensive economic benefits from the change. But Thorpe's body didn't bring the promised Football Hall of Fame, museums, shrines, and new hospitals. A municipal split personality developed, in which there were Thorpers and Chunkers.

But lifetime residents younger than 60 have always believed they lived in a town called Jim Thorpe - and most who are older would just as soon forget the whole thing.

Besides, the community has evolved from a dying coal town into a modest tourist mecca, and on a recent day downtown, Jim Thorpe was crowded with visitors who had come to ride the scenic railroad.

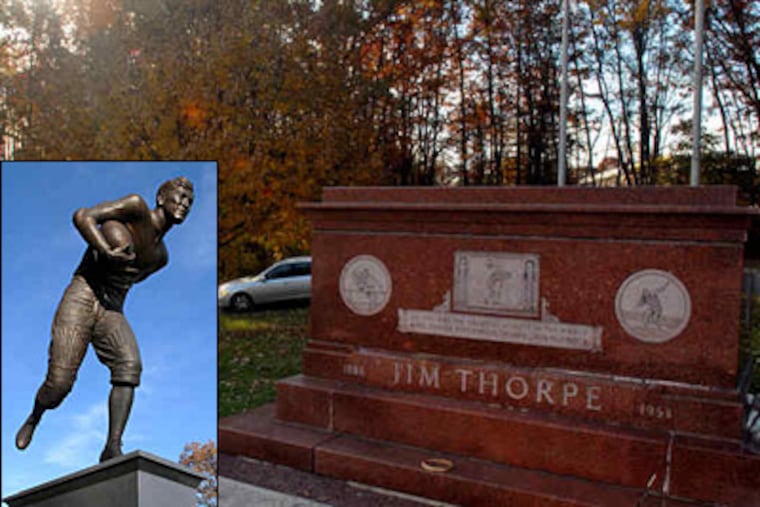

About three miles out of town, a rectangular, red-granite mausoleum bears images of Thorpe's life carved in relief. There are poses of Thorpe running, hurdling, jumping and throwing, hitting a baseball, and fending off a tackler on the gridiron. Underneath runs the legend: "Sir, you are the greatest athlete in the world" - King Gustav V, Stockholm, Sweden, 1912 Olympics.

There is only limited parking on a gravel strip, but it doesn't matter, because nearly all the cars that pull in are merely using the semicircular drive to make U-turns.

"The grave site is a contemplative place," said Don Hugos, president of the Jim Thorpe Chamber of Commerce. "It's not what attracts people here, but we're not going to give up Jim Thorpe's remains. We have honored his name, and every year on May 28 we still have a celebration of his birthday.

"Besides, the name change is what started the restoration of this town," said Hugos, a photographer with a downtown gallery.

Jack Thorpe, who is 72, said he and his brothers, Richard, 77, and Bill, 81, were united in their intent to seek the return of their father's remains. They had planned to make this move in 2001, but they were deterred by the opposition of their sister, Grace, who died last year.

Jack Thorpe said he had tried to persuade borough officials to return the remains and had hoped to avoid a lawsuit.

"We believe the people of Jim Thorpe, Pa., acted on good faith when they honored our father," he said. "We'd still like to work with them on this. The town is already a great success, and they don't need the bones of my father. I don't think the people of Jim Thorpe understand Indian culture and how important it is that our father be properly laid to rest."

Sean W. Pickett, a lawyer in Kansas City, Mo., and specialist in American Indian rights, said the suit would be filed this month and contend that the borough was obligated to surrender the remains under the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. The law requires federal agencies and institutions that receive federal funding to return American Indian cultural items and human remains to their peoples.

"We are going to argue that because Jim Thorpe Borough receives federal funding for housing, community development, and education, they are subject to the requirements in NAGPRA," Pickett said.

Jack Thorpe said his father had told him and his brothers that he wanted to be buried in Garden Grove Cemetery, which is northeast of Shawnee in Pottawatomie County about a mile from where he was born and where his father, Hiram, and several other relatives are interred.

Jim Thorpe was born in 1887 on the Sac and Fox Indian Reservation and given the Indian name Wa-Tho-Huck (Bright Path). He came to Pennsylvania to attend the federal Indian Institute at Carlisle, where he led the school's football team to victories in 1911 and 1912 over the big college teams of that era. Thorpe went to the Olympic Games in Stockholm in 1912 and won gold medals in the pentathlon and decathlon.

Thorpe played professional football and baseball after the Olympics, and two years after he retired from football in 1929 he was working with a pick and shovel for $4 a day, most of which he spent on whiskey. He went through three wives, a series of short-lived jobs, and a national tour with a song-and-dance troupe called the Jim Thorpe Show.

Thorpe died of a heart attack March 28, 1953, in a house trailer in Lomita, Calif. His third wife, Patricia, whom he married in 1945, set out to find a final resting place for him and liked the idea of having a town change its name to Jim Thorpe. She went to Philadelphia in September 1953 to get help from Bert Bell, the commissioner of the National Football League and a longtime Thorpe friend. She heard on the radio in her hotel room that a small town 90 miles away was raising an industrial-development fund.

She offered the town a deal, and the town accepted. To show her good faith, she brought the body to town before the vote on the name change. It was disinterred in Tulsa, Okla., and 10 days later arrived by train in Allentown, where it was transferred to a hearse and brought by motorcade to Mauch Chunk. Children, given the day off from school, and adults lined the streets to watch the procession come into town and go to Evergreen Cemetery, where Thorpe's body was placed in a temporary crypt. It was Feb. 9, 1954. Thorpe had been dead 11 months.

The renaming was approved May 10, 1954, by a 10-1 ratio, and the next day Patricia Thorpe and five officials of the new community signed a remarkable contract in which the real property was a corpse. It provided that so long as the town was named Jim Thorpe, Thorpe's body would remain in the town. Three years later, the mausoleum was ready, and Thorpe's body - after four moves, nearly 3,000 miles of travel, and more than four years after he died - was laid to rest.

"I understand the family's point of view, and I would hate to get in a legal battle with them," said John McGuire, Borough Council president and a lifelong resident. "But Jim Thorpe is the heart and soul of this town. . . . He's such a part of us that we could never consider losing him."