Last picture show at I-95 underpass cathedral

There are dozens, perhaps hundreds, of empty acres under and alongside the highways that slice up Philadelphia's urban grid, but only one of those spaces gets transformed, Cinderella-like, into an art gallery on the first Sunday in May. Like the storybook character, this waste ground has but a few fleeting hours to enjoy its finery. Then, poof, it all vanishes into the mists of I-95 exhaust.

NOTE: This archived story ran May 1, 2010.

There are dozens, perhaps hundreds, of empty acres under and alongside the highways that slice up Philadelphia's urban grid, but only one of those spaces gets transformed, Cinderella-like, into an art gallery on the first Sunday in May. Like the storybook character, this waste ground has but a few fleeting hours to enjoy its finery. Then, poof, it all vanishes into the mists of I-95 exhaust.

For that wondrous metamorphosis, Philadelphia owes a debt of gratitude to the artist Zoe Strauss. Every year for the last 10 years, she has organized a guerrilla-style show of her photographs in the highway umbra between Mifflin and Moore Streets. Attending this underground event - underpass event? - makes you instantly feel part of the cool crowd.

This year's exhibit, from 1 to 4 p.m. Sunday, marks the end of Strauss' free road show. It will be the last time that the former Whitney Biennialist sweeps up piles of broken glass, whitewashes graffiti, and glue-sticks her unframed color photos to the concrete pillars. Now 40, and a successful artist whose gritty photos are displayed at museums and sell for as much as $2,500 a print, Strauss has decided the event has run its course.

"I didn't want to overwork it," she explained the other day as she eyed this year's accumulation of debris and calculated the number of interns who would have to be pressed into service to clear it away.

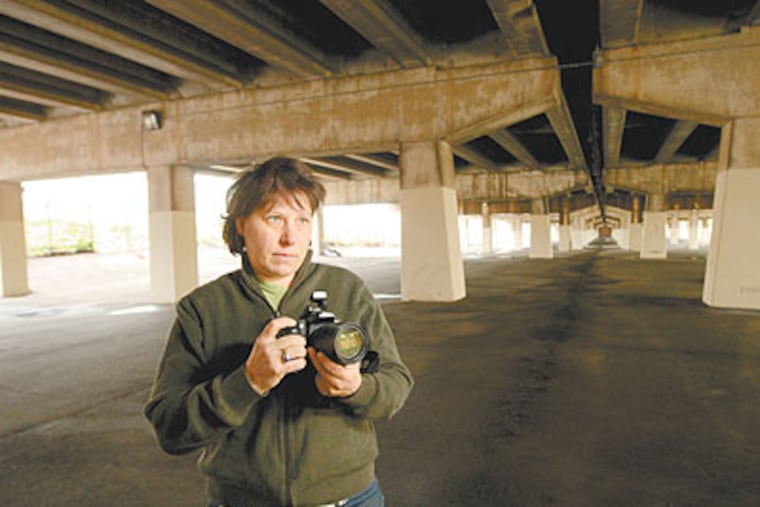

Even though the asphalt cavern was still in its normal unkempt state, it wasn't hard to understand what attracted Strauss. At the midpoint of the road's undercarriage, the concrete beams and columns rise up like a cathedral vault, then part slightly to admit a celestial shaft of sunlight - the center line rendered in luminescence, with nature as the photographer.

"It's like you're in a Renaissance painting, with the columns receding in perspective," said Peter Barberie, an admirer and photography curator at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Who knew that old 95 concealed such architectural grandeur?

It's pretty clear that Strauss has been organizing the exhibit only partly to show us the pictures. Her ulterior motive was always to make Philadelphia understand what these unwanted, leftover spaces can be.

"The space," Strauss explained, "was the impetus for the installation."

She had never shown her work in a formal gallery when she staged her first guerrilla installation in 2000. In truth, Strauss had not even done much photography. But she was seized with the idea of making art "accessible to people who happen upon it," so she assembled her best photos, printed them on good ink-jet paper, and stuck them on the concrete columns unframed. She simply appropriated the space without bothering to find out whether she needed a city permit.

If her intention had been to subvert the art world's gallery system, she could not have hit on a more symbolic gesture. At the end of the three-hour show, she figured she would abandon the images to the wind and sun.

Except that Strauss' accidental viewers liked them so much that they peeled them off the walls to take home. After that, salvaging a Strauss became a tradition, and she had to impose a one-per-person limit, as well as a strict rule that they could not be removed before the show's end at 4 p.m. A few minutes before the appointed hour, a strange ballet would begin: Those in the know would stand next to the column where their target photo hung until, at precisely 4 p.m., the rrrrrip of peeled paper would echo in unison through the space, counterpointing the continuous thudding of traffic.

Philadelphia can only hope that some Person of Power will happen by Sunday and be fired up enough to see that other wasted spaces around the city can be furnished with similar activities. Or maybe there is another enterprising citizen out there with a great idea who will claim ground for his or her purposes.

However it happens, those scraps of land are one of the city's great untapped resources. I-95 cruelly separates Philadelphia's original riverfront neighborhoods from their birth river, but the gap would feel less daunting if there was more activity. The same goes for the Ben Franklin Bridge and other viaducts. Many cities have discovered that overpasses are tailor-made sheds for farmers' and flea markets.

Philabundance, the regional food bank, recently recognized the highway canopy as a perfect distribution point. On Monday, a line for free poultry and beef stretched more than two blocks, a sight that was catnip to a photographer like Strauss, whose work often focuses on the hard side of life.

She immediately sidled up to Arnetta Bostic, 70, of Whitman Park, who carried a stunning shopping bag imprinted with photos of the first family. In minutes, Strauss and Bostic were friends. Out came a Nikon D300, Strauss' sole photographic tool, from a small faded tote she had received for her 16th birthday. A few frames were snapped, but they seemed almost incidental to the encounter.

Viewers often marvel at how Strauss manages to capture individuals in intimate moments of expression. They gladly reveal to her their hidden tattoos, scars, old hurts, and bad habits. One of her most disturbing images, one of a woman inhaling smoke from a crack pipe, was enlarged for the window of the Institute for Contemporary Art when she had a show there in 2006 on - where else? - the museum ramp.

But Strauss ranges widely in her choice of subject matter. She traveled the country to produce her book America. "She uses many pictures to create an epic narrative," said Barberie. "The work is really about America right now, tough and poignant, in the tradition of Walker Evans and Robert Frank. She captures a time and place."

She never fails to come back to Philadelphia, a city where she manages to find deep meaning in corner stores, listing rowhouses, and old walls that have been stuccoed over and painted with various promotional messages. Strauss likes to photograph facades, of both the human and the masonry kind, as well as the backs of things. Ultimately, her photographs seek to decode the patterns in the everyday world around us.

Since this is the last picture show under the highway, Strauss said she would make an exception and sign her prints, an acknowledgment perhaps that they were no longer accidental trophies of urban living, but formally recognized works of art. Still, her Web site includes the same severe message that has always appeared before, highlighted in capital letters:

"MAKE SURE THAT NO PHOTOS ARE TAKEN DOWN UNTIL 4PM! I WILL KILL IF ANY ARE TAKEN DOWN BEFORE THEN ... I WILL KILL, I WILL KILL AND I AM NOT KIDDING."

The space under I-95 remains, after all, a gritty place where almost anything can happen.