Second grand jury report blasts Pa. gaming board

A state grand jury on Tuesday slammed the Pennsylvania Gaming Control Board, characterizing it as a patronage-filled, secretive agency that failed to safeguard the public by inadequately investigating casino operators and vendors.

A state grand jury on Tuesday slammed the Pennsylvania Gaming Control Board, characterizing it as a patronage-filled, secretive agency that failed to safeguard the public by inadequately investigating casino operators and vendors.

The two-year investigation found that gaming board officials interfered with background checks and omitted key facts from reports on the suitability of applicants for potentially lucrative casino licenses.

The grand jury's 102-page report portrayed an agency that was in far too big a rush to get casinos up and running, did much of its business behind closed doors, and gave some applicants preferential treatment.

And when some gaming board staffers were called to testify to the grand jury, the report said, they suffered from "collective amnesia."

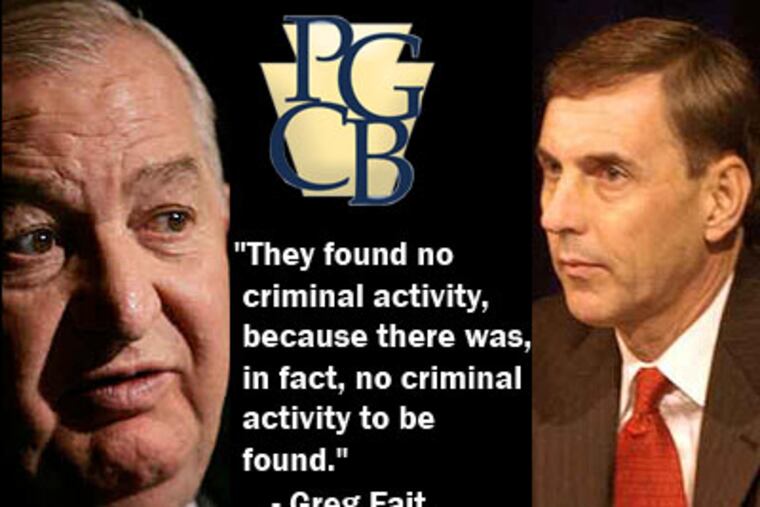

The board's chairman, Greg Fajt, swiftly labeled the report a rehash of "old news" containing no proof of any wrongdoing by the board or its employees.

"After this grand jury met for more than two years, there were no arrests . . . no indictments," Fajt noted in a statement. "They found no criminal activity, because there was, in fact, no criminal activity to be found."

State Rep. Curt Schroder (R., Chester), chairman of the House Gaming Oversight Committee, said the lack of indictments did not dilute the importance of the findings.

He stressed that it was the second grand jury to call for taking the investigative role away from the gaming board. In 2008, a Dauphin County grand jury said investigations of gaming applicants should be overseen by the state police or the attorney general.

Fajt "should open his eyes and realize what a significant problem this is," said Schroder, vowing to have his committee hold hearings on the grand jury's findings and consider legislative action.

Spinning off the gaming board's investigatory functions was one of 21 recommendations in the report.

It also urged that commissioners be barred from meeting in closed-door executive sessions to deliberate on license applications.

The grand jurors took aim at the regulatory side of one of the biggest changes wrought by the General Assembly in recent memory: the legalizing of gambling in 2004. In the last five years, 10 gaming halls have generated $5.1 billion in tax and license-fee revenue. The industry is overseen by the board, whose five members are appointed by the governor and legislative leaders of both parties.

The report said the board became "preoccupied, fixated, and singularly focused on making the licensing process fair to the applicants at the expense of adequately protecting the citizens of the Commonwealth."

"No applicant was ever deemed unsuitable," the report said, "despite its clear existence in some cases."

The jurors focused on the history of four casino applications: Presque Isle Downs in Erie; the Mount Airy Casino partnership in Mount Pocono; and PITG Gaming L.L.C. and Station Square Gaming, both in Pittsburgh.

When Presque Isle Downs applied, the grand jury said, board investigators were told not to conduct certain interviews and were prevented from requesting additional information from the applicant.

The investigators, many of them former police or federal agents, uncovered problems with at least 15 people connected to the project: past gambling-related convictions; employment by known organized-crime figures; tax evasion; even murder convictions. But the report said those facts were never marshaled in a way that would have obliged the board to consider the character of the applicant group as a whole.

Instead, in 2006, the Presque Isle Downs group got its license - with the board stating that the investigation had unearthed no evidence of "unsuitable character."

Regarding the Mount Airy application, the report said that at the last minute, some board officials removed about four pages of sensitive information about the "honesty, character, and integrity" of the applicants, including Louis DeNaples, a controversial northeastern Pennsylvania businessman.

The report said the excised information included accounts of alleged links between DeNaples and members of organized crime.

DeNaples, who bought the Mount Airy Lodge to convert it into a gaming hall, won his license in 2006 - but later was charged with lying about his alleged ties to mobsters. Prosecutors dropped that charge on the condition that DeNaples not associate with the casino.

In all four licensing proceedings, the report said, key data gathered by board investigators were omitted from "suitability reports" to the board - and when board staffers were called to testify about this to the grand jury, they often had no recall.

"It is inconceivable that an entire group of employees could have collective amnesia regarding a vital aspect of their job," the report said.

When PITG Gaming sought a license, the jurors said, a final assessment of the group's suitability omitted the fact that the main investor, Donald Barden, had lost $11 million at casinos.

Barden's "financial history and corresponding level of risk was wholly ignored by the board," the report said. Barden won a license to build the Rivers Casino in Pittsburgh - but was he unable to finish the project. Casino operator Neil Bluhm had to take over construction and operation of the casino.

The rush to establish gaming in Pennsylvania dictated the thoroughness of some investigations, the report said.

In one case, it said, the board approved a license for a computer-system contractor before board investigators had completed their work.

Not that anyone noticed: The grand jury said the investigators were so out of the loop that they did not know the entity they were investigating had already been licensed.

Then there was political patronage: Resumés for job applicants came stamped with the names of supporting legislators. A former director of communications, Nicholas Hayes, testified that edicts from legislators amounted to "this person must be hired."

Hayes recalled having to hire a media aide at the behest of a former board member. That hire ended poorly, Hayes testified - the aide was arrested for murder.