How city agencies failed to save 6-year-old Khalil

When police arrested the parents of Khalil Wimes and accused them of starving and torturing their 6-year-old son to death, Mayor Nutter decried the boy's demise as tragic, but said the city could not have prevented it.

When police arrested the parents of Khalil Wimes and accused them of starving and torturing their 6-year-old son to death, Mayor Nutter decried the boy's demise as tragic, but said the city could not have prevented it.

Philadelphia's Department of Human Services had no official oversight - no "open case" - for Khalil Wimes, the mayor stressed. "None," Nutter told reporters in March. "Next question."

In fact, Khalil had spent the final months of his life beaten, bone thin, desperately ill, and out of school - and DHS had failed to see what was right in front of it.

An Inquirer review of Khalil's death - including interviews with his siblings, foster parents, and other family members, and a review of police reports, court documents, and DHS files - found the city missed many chances to save him.

The child welfare system plucked Khalil from a safe home and put him in jeopardy in the first place, then failed to rescue him when he was hurt, The Inquirer review showed.

Intent on reunifying him with his family, in 2008 the agency endorsed returning Khalil to the care of his birth parents - even though DHS had previously pulled seven of his older brothers and sisters from their custody for neglect.

Khalil was returned over the fierce objections of his court-appointed child advocate and the foster parents in whose care he had thrived.

In the last eight months of Khalil's life, city social workers saw him eight times during visits to his home and at a DHS facility, but didn't recognize that he was a child in great danger.

As Nutter said, DHS had no open case on Khalil. But its social workers were engaged in official oversight over two of his siblings. This assignment put them inside Khalil's South Philadelphia apartment and at the DHS center where agency staff supervised gatherings that Khalil and his parents had with other siblings.

Four times DHS visited the apartment where the boy spent his last days in a latched, empty bedroom on a soiled, plastic mattress. He was never enrolled in school. His parents claimed they were home-schooling him. There is no indication DHS ever verified that with school officials.

During these months, Khalil's parents beat him regularly, with books, shoes, extension cords, and a belt, according to interviews with two adult sisters. Three large welts on his forehead are visible in an October 2011 family photograph.

The signs of Khalil's abuse and deteriorating health were visible during DHS visits, according to family members. The social worker questioned Khalil's mother about his scars and bruises but did not act.

Khalil was dead from head trauma when his parents - Floyd Wimes, 48, and Tina Cuffie, 44 - brought him to the Children's Hospital of Pennsylvania on the night of March 19.

His corpse was "extremely emaciated" - weighing only 29 pounds, just over half the weight of an average boy his age - and bore a sea of scars across the face, neck, back, arms, and legs, according to court documents and police reports obtained by The Inquirer. Investigators believe he had been abused for as long as two years.

"There was no surface of his body that didn't have an injury," said First Assistant District Attorney Edward McCann.

Cuffie told police that Khalil vomited constantly - he had lesions throughout his mouth - but she acknowledged she hadn't brought him to a doctor in more than a year.

Doctors at Children's Hospital called police immediately. Within hours, detectives charged Wimes, who also has used the name Latiff Hadi, and Cuffie with murder. They are to face their preliminary hearing Wednesday.

The last home visit by social worker Courtnei Nance took place two weeks before Khalil's death.

Khalil's story is a blow to an agency that implemented sweeping changes in the aftermath of the 2006 death of 14-year-old Danieal Kelly, found starved and abused and weighing just 42 pounds.

DHS officials said Nance could not discuss Khalil's death because of confidentiality requirements. The agency also declined to comment.

In March, Nutter promised a full city investigation of what he called a "very complicated" case.

On Monday, Nutter's spokesman, Mark McDonald, said the mayor's March comments reflected an initial and incomplete briefing from DHS. Nutter had received a fuller briefing in recent days, McDonald said, and an investigation was ongoing. He would not comment further.

Frank Cervone, executive director of Support Center for Child Advocates, said that while the ultimate blame lies with those who abused Khalil and family members who did not report it, professionals missed opportunities to save him.

"You see the child, you think there's trouble. . . . It's time to act," he said.

Khalil's life wasn't always brutal.

Until he was 3, Khalil lived in the care of his foster parents and slept with his favorite Diego doll in a blue bedroom with an alphabet border. He had a sports-themed comforter, a dresser, a tiny chair, and a television so he could watch Shark Tales and Backyardigans. In the mornings, he liked to pull his toy box and books from the closet, and count his playthings aloud, "One, two, three, four."

He had regular doctor visits and natural nut milk to curb his asthma.

This was the life provided by his West Philadelphia foster parents, Alicia Nixon, now 35, and her husband, J. Evans, now 41.

Khalil called Nixon "Mommy" and La Reine Nixon, his doting foster grandmother, "Mimi." They called him "Lil Lil."

By all accounts, Khalil flourished in the Nixons' care.

"Khalil is a very energetic and active toddler," read a DHS report. "He is very alert and appears to be attached to his kinship/family home."

"We loved everything about him," said La Reine Nixon. "The way he looked, the way he smelled - everything he did."

Summer days he spent with La Reine Nixon at the University City Pool Club, or making scribbly paintings in the studio of Nixon's Overbrook Art Gallery.

Alicia Nixon took in Khalil a week after he was born on Valentine's Day 2006.

Alicia Nixon is a distant cousin of Floyd Wimes'. She had not seen him since childhood, but received a call from a mutual relative the month before Khalil's birth, asking if she could take the expected child in while Floyd and Tina got on their feet.

Wimes and Cuffie were living in a rowhouse with no heat, no hot water, or gas in the shadows of the El at 56th and Market Streets when they had Khalil. There were holes in the floors and ceilings.

"Their home is not suitable for children," read a DHS report. The reasons for taking Khalil out of Wimes and Cuffie's custody included "substance abuse" and "the parenting skills for both parents."

DHS had already removed all five of Khalil's older siblings from the couple's care, as well as two of Cuffie's adult daughters from a previous relationship, who were in the child welfare system until age 18.

Going back to 1995, the agency had received 11 neglect and abuse complaints against Wimes and Cuffie, and investigated allegations of sexual abuse between the older children.

Cuffie had given birth to one son with drugs in his system before Khalil. She tested positive for marijuana and crack cocaine while pregnant with Khalil, the records show.

Alicia Nixon knew none of this when she took Khalil in a week after his birth. She had no children of her own. She wanted to help the child.

"We were trying to avoid yet another Wimes stuck in the system," she said.

With the recommendation of DHS - and the agreement of Wimes and Cuffie - Alicia Nixon was granted temporary legal custody of Khalil. The parents could visit every few days.

Nixon gave Wimes and Cuffie a car seat and a stroller, and bought clothes, Pampers, and toys for Khalil. She scheduled his medical appointments.

Wimes and Cuffie arrived for their visit looking disheveled and brought Khalil back dirty and soiled, Alicia Nixon said. On one occasion, Wimes and Cuffie didn't bring the infant back at all.

Police found Khalil with Wimes and Cuffie on the porch of the crumbling Market Street house. In the chilly morning air, Cuffie undressed Khalil down to his diapers before giving him to Alicia.

"These are my clothes," Alicia said Cuffie answered. "I bought these."

Khalil's parents were soon restricted to weekly two-hour supervised visits in a playroom at Family Court.

In February 2007, two days after Khalil's first birthday, Wimes and Cuffie, who were still living in the Market Street house, tried to get Khalil back during a hearing at Domestic Relations Court.

Cervone, of the Support Center for Child Advocates, said this preliminary step in the Family Court process is badly in need of improvement. With thousands of children passing through Domestic Relations Court each year, the process is less than ideal.

"There are a tremendous number of cases and minimal information," Cervone said. "Judges are often asked to make best-interest decisions of the child with virtually no objective information. It's little more than a coin toss."

Wimes and Cuffie's DHS file did not make it down to Courtroom 2 that day, court transcripts show.

Judge Robert J. Matthews gave Khalil back to Wimes and Cuffie. "They are the mom and dad," Matthews said.

A frantic Alicia Nixon called Jessica Campbell, Khalil's DHS social worker at the time, who banged on Wimes and Cuffie's door for four days to check on Khalil's safety, but could not find them. Alicia and La Reine Nixon worked the phones.

Five days after being returned to the care of his parents, Wimes and Cuffie brought Khalil to Children's Hospital filthy, dehydrated, chaffed, and suffering from an asthma attack. Doctors notified DHS, and after two days in the hospital Khalil was released to Alicia Nixon's care.

Alicia Nixon threw Khalil a welcome home party. He sat in his high chair, giggled, and ate smashed bananas.

"We had to do something to let him know that he was home - that everybody missed him and loved him," Alicia Nixon said.

Wanting to move toward adopting Khalil, and with the encouragement of DHS, Alicia Nixon began the demanding process of becoming certified as a foster parent. Not wanting to confuse him, Alicia Nixon tried to get Khalil to call her "Jummy" - "Mommy" in Arabic - but he began calling her Mommy.

"I love you, Mommy," he'd say.

"No, I love you more," she'd reply.

He took his first steps, learned numbers and shapes.

"Oct-eee-gon," he'd giggle at stop signs. "We had a "timeout chair," Alicia Nixon said. "He'd smile and say, 'No, Mommy, I don't want to go to chair,' and that was the most discipline he knew."

The decision to return to Khalil to Wimes and Cuffie, when Khalil was almost 3, was as crushing as it was unexpected for Alicia Nixon.

By this time, after six years of failing to find sobriety or safe housing, DHS had terminated Wimes and Cuffie's rights to five of Khalil's siblings. But the window was left open on Khalil, since he had been in the system for less time.

DHS set three goals for Wimes and Cuffie to get Khalil back: six months of drug treatment, find an apartment, get work. They also had to take a parenting class.

The core tension facing any child welfare system is the balance between keeping families together and protecting children, Cervone said.

But given the removal of seven previous children, the bar for Khalil should have been much higher, Cervone said - the agency could have asked for a longer period of sobriety and more intensive psychological treatment.

"The system treated this case as if it was the parents' first removal," he said. "They were given an easy test and it should have been made a lot harder."

Wimes and Cuffie managed to meet the agency's goals for a six-month period in 2008. Cuffie provided three clean urine samples and attended a parenting class. Wimes got a construction job paying $10.11 an hour.

The 2008 Family Court hearing on Khalil's future came before Judge Charles J. Cunningham - the same judge who had presided over the agency's removal of Wimes and Cuffie's other children.

After Floyd Wimes testified that he and Cuffie had found an apartment, a DHS lawyer said the agency was now in favor of sending Khalil back to his birth parents, since they had met their goals.

"Your honor, we would be working toward reunification at this point," she said.

The social worker, Campbell, was strongly against sending Khalil back to Wimes and Cuffie, according to DHS files and her correspondence with the Nixons. The judge asked her opinion, but Campbell could not testify over objections from Wimes and Cuffie's attorneys.

"A social work perspective is irrelevant," said Wimes' attorney. The DHS attorney remained silent. Alicia Nixon was not given a chance to speak.

Monique Sherman, Khalil's court-appointed child advocate, argued against sending Khalil back to Wimes and Cuffie. Their most recent drug treatment reports were taken three months earlier, she argued, and her records described Floyd Wimes' treatment attendance as "sporadic." Khalil had bonded with his foster parents after three years of care, she said. And Wimes and Cuffie were unsafe, said Sherman.

"The problem I am having with this is that the only time this child was in the parents' care, he was seen on the street without appropriate clothing, he wound up in the hospital, he had an asthma attack," she said.

She requested more evaluation for "Khalil's best interests," wanting to see the couple "are able to actually parent this child."

But the "legal standard" had been met, the judge said. Wimes and Cuffie were the biological parents. Khalil would be returned to their custody, going back to them after eight overnight visits to test their care.

"If Khalil comes home to visit overnight, he's going to have a bed and all that?" Cunningham asked.

"Yes, I will make sure," Wimes said.

Alicia and La Reine Nixon did not stop fighting.

They flooded DHS with e-mails and phone calls requesting an appeal. Alicia wrote long letters describing the change in Khalil's behavior - a sense of fear - she witnessed after the scheduled overnight visits with Wimes and Cuffie.

"Once again, he fussed all the way home from some invisible thing that he was clearly upset with," she wrote in detailed notes describing his behavior.

They called the mayor's office, who directed them back to DHS.

"When they get him back, they are going to destroy him," La Reine would cry.

La Reine Nixon wrote Judge Paula Patrick, who presided over a final hearing on Khalil's future in March of 2009.

"We need a voice of reason," La Reine Nixon wrote.

Again, DHS endorsed sending Khalil back to Wimes and Cuffie, over the strong objections of Sherman, the child advocate.

"The law is clear" in favor of the biological parents, Patrick said.

Campbell, the social worker, wrote the Nixons with her "heartfelt apologies." She could not agree with the decision to send Khalil back, but, legally, the judge's "hands were tied," she said.

The child welfare system and the legal system are often adversarial at best, she explained.

"Irreparable damage is done to our families and children. It's really unfair," she wrote. "The child welfare system needs a great deal of improvement, and sometimes things need to be shaken up for really meaningful change to follow."

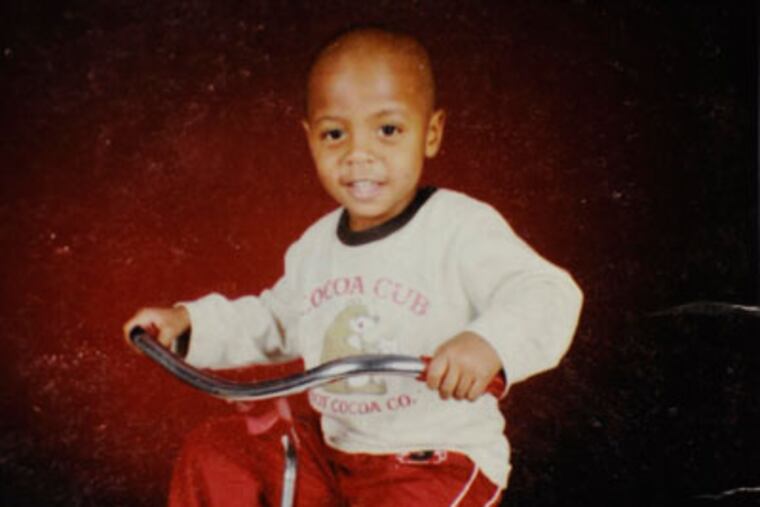

In the days before Khalil was scheduled to be taken away, Alicia took him for a professional photograph. He smiled atop a little red bicycle. The night before he left, she took him to his favorite restaurant, J.B. Dawson's, where he liked to scoop mashed potatoes up with brown bread, and the waitresses gushed over him.

"What's wrong, Mimi?" Khalil asked La Reine. "Why you crying?"

After dinner, the family said as many goodbyes as could be said, and Alicia and La Reine took Khalil home for their last night together. They didn't make him go to bed. They stayed up playing and talking, and fell asleep on the couch.

In the morning, a social worker arrived to take Khalil to Wimes and Cuffie. Khalil didn't understand that he would not be coming back, Alicia said.

Alicia recorded Khalil's voice. On a recent afternoon, she played it aloud.

"I love you, Mommy."

"No, I love you more."

"I love you, Mimi."

"No, I love you more."

Some people told Alicia and La Reine they should be able to get over it since they weren't the birth parents.

Others said that when he got older, he would come looking for them. He won't forget you, they said.

La Reine couldn't bear to even hear his name, or see a photo of him. She couldn't function with the thought of Khalil waiting for Mommy and Mimi to come pick him up.

Alicia grieved differently. She talked about him all the time.

Wimes and Cuffie ruled out Alicia and La Reine having any contact with Khalil, but the Nixons had found out where they lived.

Sometimes, Alicia and La Reine would park on the street outside, desperately wanting to knock on the door, but worried that if they did, they would get in trouble and lose any chance of seeing Khalil again. So they would sit, hoping for a glimpse.

But Khalil never came outside.

DHS monitored Khalil for one year after returning him to his parents - a lengthy period of time that Cervone said reflected well on the Philadelphia system.

The abuse started almost immediately after the monitoring stopped, said Khalil's two sisters, Randee, 24, and Tiffany, 23, who often visited or slept in the apartment. They did not report the abuse because they did not want their mother to lose custody of her children. (Randee Cuffie has had two of her own children removed by DHS for neglect.)

It took some time for Khalil to get used to Cuffie, and that caused tension, Randee Cuffie said. Khalil did not like to eat the chicken Cuffie cooked. And he wouldn't drink regular milk, still preferring the natural nut milk.

There were some good days, Randee Cuffie said, like family trips to a Phillies game and to the Please Touch Museum, where Khalil sat behind the wheel of the big toy SEPTA bus.

But the bad days became more frequent. Wimes used his fists and extension cords, shoes, books, and belts, said Randee.

"If he didn't say 'good morning' to my mom, Floyd would take a belt and beat him on his butt," Tiffany Cuffie said of Khalil.

Tina Cuffie beat Khalil too, the siblings said, "but more disciplinary-wise."

"She would wait till he did something two or three times," Tiffany said, "then beat him and explain to him why they beat him."

Wimes and Cuffie did not hurt Khalil's 3-year-old sister Maiya, the siblings said. Wimes and Cuffie treated her well, the siblings said, scheduling doctor appointments and enrolling her in preschool.

Wimes and Cuffie often withheld food from Khalil as punishment for what they deemed to be misbehavior, sometimes not feeding him until dinner time, or sending him to bed without dinner, the siblings said.

Around last summer, Khalil began throwing up after he ate, sometimes twice a day, both Tiffany and Randee Cuffie said.

Wimes and Cuffie believed Khalil's vomiting was psychological - that he was doing it on purpose, the sisters and other family members said.

In August 2011, Khalil threw up twice at a birthday party in Southwest Philadelphia for Cuffie's father, Wesley Cuffie Sr. In a photograph from the party, Khalil looks frail and sick.

Khalil didn't mingle with the other children that day, Wesley Cuffie Sr. said. "He just sat there on the step like a little tin soldier," Cuffie Sr. said.

None of Cuffie's relatives who were at the party called authorities about the boy's condition.

Sometimes at night, Khalil would sneak from his bedroom to the refrigerator for food, Tiffany and Randee Cuffie said. He would steal cake or fruit or whatever and then go back to his room, and they would hit him for it, Randee Cuffie said.

It was around Thanksgiving that his parents hammered the lock on Khalil's door to keep him in at night, the sister said.

If he soiled his bed, which he did often as his stomach worsened, he would be beaten for it, Randee said.

Khalil's toddler's bed for a time broke during one beating last year, the siblings said. His room had no other furniture - Wimes and Cuffie threw it out after a bedbug infestation, Randee Cuffie said.

He had no toys in his room. Wimes and Cuffie got rid of them because he was throwing up on them, Randee Cuffie said.

Wimes and Cuffie decided to "home-school" Khalil last September rather than enroll him in kindergarten, the sister said, because they were "worried about the marks on Khalil - that a teacher would see them and call DHS."

The beatings only worsened with Khalil's lessons, she said.

"Floyd would pop him on the side of the head or call him stupid and make him stand in the corner," Randee Cuffie said.

Crime scene investigators found dried blood in many rooms of the apartment.

DHS reentered Khalil's life in August 2011, at a time when his abuse was getting worse. As the social worker for two of Khalil's older siblings, Nance was assigned to supervise and monitor visits between Khalil, his little sister, Wimes and Cuffie, and two of his older siblings, who were in foster care after failed adoptions.

Though there was no official open case on Khalil, the aim of the visits was to strengthen relationships between him and his brothers and sisters.

Nance monitored three visits in the playroom of DHS's Achieving Reunification Center at Seventh and Market Streets. She also supervised three two-hour home visits between November and February at Wimes and Cuffie's apartment.

And two weeks before Khalil was killed, Nance visited the apartment for a 15-minute interview with Tina Cuffie and another relative.

Khalil showed visible signs of abuse during this period, his siblings said.

In one photo taken during a visit last fall at the DHS center, Khalil sits in Cuffie's lap. He has two bruises on his forehead and his undernourished arms poke out from his T-shirt.

In another family photograph taken that fall, Khalil has three large welts across his face - wounds Randee Cuffie said were the result of a beating she witnessed.

During her visits with the children, the social worker spotted similar bruises on Khalil, according to sources familiar with the city's investigation into Khalil's death.

Tina Cuffie told the social worker the facial bruises were from a fire-truck toy his little sister had thrown at him, said the sources.

As for the bruising on Khalil's arms, Tina Cuffie blamed them on Khalil's eczema.

Khalil threw up during a March 3 visit inside the playroom at the DHS center. Wimes made the child stand in the corner as punishment, according to Tiffany Cuffie, who was at the visit.

At some point, the social worker inquired about Khalil's frail frame. Tina Cuffie told her she had been taking Khalil to doctors at Children's Hospital for an eating disorder, and that her male children were generally small. Though supervising the children, the social worker was unaware of the parent's long history of neglect, the sources said. It's unclear why not.

Cervone, from the Support Center for Child Advocates, said it should not matter that the social worker - a mandated reporter of child abuse by law - was not specifically assigned to Khalil.

"A professional was in the company of a child who was in trouble, perhaps manifestly so," Cervone said. "We now know looking back that the child likely had bruising, injuries, weight loss. You have to have the eyes to see this."

Because of the history of the family, the agency should have been on the lookout for danger - for all the children, including Khalil, he said.

One of the agency's favorite lines is that the family is the client, Cervone said. "That means you're looking at the whole picture. That's the breakdown here."

There was a scheduled visit for March 17, two days before Khalil was killed, according to the DHS files.

Cuffie and Wimes canceled.

According to police reports, Tina Cuffie struck her final and fatal blow on the morning of March 19 inside the bathroom.

"I popped him in the back of the head and knocked him to the floor," she told police. "He fell flat on his face and split his lip. He didn't even try to break his fall."

The couple waited 10 hours before bringing his body to the hospital.

Nobody bothered to call Alicia or La Reine for two days.

La Reine was in her art gallery when a friend called. He had seen something on the evening news about a 6-year-old child killed by his parents in South Philadelphia.

Alicia was driving home from work when she got the call from La Reine.

She pulled over. "No, no, no, no. . . ."

Khalil was still at the morgue. Nobody had claimed him.

Before the funeral, his foster parents had a private moment with Khalil at the funeral home.

Alicia Nixon didn't want to see Khalil - not this way. But she had to. La Reine Nixon wanted to hold him. They were led into a private room. Alicia was struck by the tiny coffin, by how small he was, like he had returned to being a baby.

Khalil was wrapped in his Muslim burial shroud, but the signs of abuse were visible on his face. There was a gash in his eyelid. His lips were split; his head lumpy from his wound.

She wanted to touch his hands and feet - the intimacies of mother and child - but he was wrapped in his shroud and she did not want to disturb him. She put her hand on his body and talked to him.

"I remember your face. I remember your eyelashes. I remember your smile, Lil Lil. I know you. I remember you. I love you. I miss you."

She closed her eyes. She did not want to remember him hurt. She wanted to remember the little boy who called her Mommy.

To view documents related to Khalil Wimes' custody, visit www.philly.com/khalilEndText