The fine Philly tradition of sneaking into events

Part of the original exterior design of the University of Pennsylvania's venerable Palestra are vertical bands of rusticated limestone that offset the building's brick facade. The stonework, obviously intended to be ornamental, can look like a ladder of sorts, with exaggerated joints between the stones, just deep enough to stick a shoe in.

Originally published May 12, 2012.

This piece was recognized by the Associated Press Sports Editors with a Top 10 Award in the calendar year for Explanatory Writing among newspapers with circulations above 175,000.

Part of the original exterior design of the University of Pennsylvania's venerable Palestra are vertical bands of rusticated limestone that offset the building's brick facade. The stonework, obviously intended to be ornamental, can look like a ladder of sorts, with exaggerated joints between the stones, just deep enough to stick a shoe in.

Since this is Philadelphia, if it looks like a ladder, it will be used as a ladder.

Getting into sports events and concerts, or just into a gym to play ball, is a fine Philly tradition. It means using your wiles and your brazenness, taking advantage of architecture or the help of an usher or a security guard, maybe someone you know from the neighborhood. Sneaking in - or more precisely, getting in, by any means necessary - is hardly a Philadelphia phenomenon, but there is evidence it has been perfected here.

Getting into the historic Live Aid concert at JFK Stadium back in 1985? The one with the most lustrous glee club in history singing "We Are The World"? The event watched by two billion people across the globe? Sure, all right.

A 20-year-old La Salle student getting on stage at Live Aid to say hello to Mick Jagger - calling him "Mr. Jagger" - and standing by Cher as she joins in the grand finale? That's Philly.

Getting into a 1967 NBA Finals game through a manhole cover? That's St. Joseph's coach Phil Martelli's tale. His CYO coach paid a guy to get the two of them into Convention Hall through the sewer system.

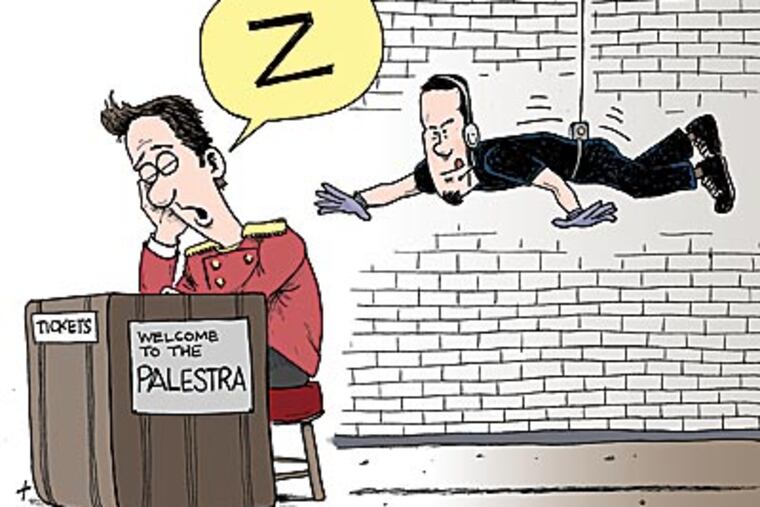

Getting into the Palestra by climbing that stonework leading to that window behind the scoreboard?

"I'd brought money. I intended to pay - it was sold out," said Rowan University men's basketball coach Joe Cassidy.

He was an undergraduate at St. Joseph's, at the Palestra to see the Catholic League high school semifinals. Scouting around the place, Cassidy was surprised to find a little line had formed behind the building. Young guys were jumping on a trash container and then scaling the side of the building. Cassidy joined the line.

"I remember Archbishop Ryan students pulled us through the window," Cassidy said. "Security saw us, but we scattered before they could get to us."

Thus, Cassidy had joined the fine local tradition of sneaking in.

It's a tradition

"I still do it," boxing great Bernard Hopkins said last summer, breaking into a big grin. "I snuck into the Jill Scott concert last week."

It was pointed out to Hopkins that most people in Philadelphia know him by sight. Didn't they recognize him?

"Of course they did, after I got in - but I was already in," said the former World Boxing Council light-heavyweight champion of the world. "By the time they see me by the front door, I'm already in through the back door. I do it all the time. . . . It doesn't matter who you are, what status you got. It's part of the tradition."

In the days when tickets cost less, ticket-takers and security guards could more easily get away with helping guys from the neighborhood, like a bartender providing free drinks. Everything from heightened security to scanners that read bar codes on tickets make sneaking in far more difficult today. The tradition, however, dies hard.

"There was a code in Southwest Philly - [if] a guy was sneaking in, you worked with him," said Dan Harrell, who has been the custodian at the Palestra for the last 23 years. "I worked at the Spectrum for a while. People were like, 'Yo, Dan, what gate you working?' I'd answer, 'I think I'm on 2 tonight,' " he recalled. "They would walk right in."

Harrell is the expert, a museum curator of sorts, on the subject of sneaking in at the Palestra.

Late this past basketball season, Harrell gave a different kind of tour of the place, showing the dirt basement underneath Hutchinson Gym next door that led up a creaky wooden staircase underneath some low-hanging pipes, to a tunnel around the perimeter of the Palestra, leading to the back entrance of a locker room that is now sealed off, but used to be unlocked and convenient.

"The only time I came to the Palestra and bought a ticket was the Catholic League playoffs," Harrell said. "I figured it was either a mortal or venial sin to sneak into the Catholic League playoffs."

There are protocols

Wherever the maneuvers, there are a couple of undercurrents in play. One is obvious and universal.

"It's just so much better if you don't pay for it," said Dan Hoban, who grew up in Southwest Philadelphia and knew his way around the doors at the Spectrum and Veterans Stadium - and said he once sneaked into a Final Four game featuring North Carolina by saying he was Jerry Stackhouse's brother. His wife, with him for this, asked who Jerry Stackhouse was.

"I'll point him out," Hoban told her.

Another aspect of getting in is an underappreciated aspect of life in Philadelphia. There is a belief in the neighborhoods that helping a friend or acquaintance adds to any experience, including getting into an event. If I help you get in, I'm part of your experience. Maybe you owe me down the line, but not necessarily.

Used to be, you might be able to blend in with the teams themselves, trying to get behind the tallest players as they walked into the Palestra or another arena. Then you'd rush into the corridor and disappear into the crowds.

One rule: Never turn around when the ticket-takers yelled at you. Another rule: Mix up your entrances so you don't become a familiar face.

An ancillary rule: If only one person could get in, he couldn't worry about his buddies.

"You only take what they're going to give," explained Tony Romano, another La Salle grad who grew up in Southwest Philadelphia.

Maybe you had money in your pocket for admission - but only if you needed it.

"At Convention Hall, one guy would go in, pay the buck to get in, whatever it was, and he'd go around the back, push open one of those doors," said Philadephia University basketball coach Herb Magee, who grew up in West Philadelphia.

There was a wall behind the building, "maybe eight feet feet [high]," Magee said.

Built as an obstacle, the wall was more of an opportunity for Magee and his friends.

"You had to jump up, catch the top, you'd be right at this door," Magee said. "If you got caught, you'd go back out, pay your way in."

Props are occasionally acceptable. A close relative of Dan Hoban's (who prefers to remain nameless, because of the alleged respectability of his current job) once called him - this was March 1996 - and asked Dan to let him borrow his referee's shirt. Hoban got it to him.

That night, the relative showed up at Drexel when the Dragons, starring Malik Rose, were playing for (and winning) an NCAA bid. Hoban's relative was with another guy, who had his own striped referee's shirt. They'd put the shirts on hangers and added a dry-cleaning bag over them (a nice touch). They ran into the gym at full speed, looking harried, asking where the refs' dressing room was.

Worked like a charm.

It's also acceptable to be consistent with your prop. For years, Dave Pauley, now the basketball coach at the University of the Sciences, rarely missed a Big Five doubleheader, starting in the late 1970s. His personal usher's jacket served as his ticket.

Not that he was an usher.

"I would wear it in - I just palmed the jacket, sat up in the corner," said Pauley, explaining this was like graduate school for an aspiring basketball coach and that every game wasn't on television in those days.

When did he stop?

"What's the statute of limitations?" Pauley quipped.

Not just for kids

Experience can be helpful in the getting-in game. A couple of decades back, a Camden Courier-Post sportswriter, Kevin Callahan, went up to State College to cover a Penn State-Notre Dame game. His father accompanied him on the trip, hoping to find a cheap single ticket.

"The problem was, 4,000 people were looking for one ticket," said Jack Callahan.

The older Callahan, who had grown up in Camden and now lives in Cherry Hill, had experience at probing for vulnerabilities. He went to the gate for visiting families and saw the guy at the gate "looked nonchalant." He also saw an inner gate where they were really checking for the tickets.

He got past the outer gate and . . . "just then [Penn State's] band came down. The band was marching down the tunnel, so I just got right behind the band," Callahan said.

He made it down to the field before a security guy asked for his tag, said he couldn't get on the field without one. But he was in.

"Just then the Notre Dame team came running on the field," Callahan said. "I looked at the coaches - they had the same color jacket I had."

So he joined in with them. A gray-haired Irish guy - he fit right in. His son could keep his seat in the press box.

"I was just a few feet from Lou Holtz in the first half," said Callahan, who is an otherwise upstanding citizen, the former chairman of the New Jersey Governor's Advisory Council on Volunteerism and Community Service.

Getting in to play, not just watch, also is a time-honored tradition.

"That's my specialty," said former Temple and NBA player Marc Jackson, a recent inductee into the Big Five Hall of Fame. "Me and a good friend . . . to work out, we used to break in [the Palestra]. Not break in, but find what door we could get in."

Jackson said they used to "to walk around for hours, for months," to find what buildings were most accessible.

Harrell, who is retiring this year, is kind of a Palestra folk hero. He began working as a custodian there over two decades back and also began taking classes part time. He earned his Penn degree in 2000 but kept working, becoming a godfather of sorts to Penn basketball players.

He couldn't quite give up his old ways, though. If someone needed in, Dan might tell them to grab a trash barrel by the back entrance and wheel it in, saying they were with Dan. Harrell claims even former Penn coach Fran Dunphy sent a few people his way when he ran out of tickets one year for a sold-out Penn-Princeton game.

"If Dan says so," Dunphy said, neither confirming nor denying.

Neighborhood lore

Every neighborhood has somebody with a story, like Tommy the Paper Boy (no last name; he has a corporate job these days). He remembers jumping onto the subway at Broad and Snyder as an eighth grader, armed with the knowledge that you could climb a metal cage - "not a fence" - outside the Vet right by the ticket window and get into the 1980 NFC championship game.

He did make sure he wore the right footwear that day.

"Between the caging and a cement pillar, there was about three inches, more or less the width of a good boot," Tommy said, remembering that a little crowd cheered him and a buddy on during their ascent.

A lot of the best stories obviously are the old stories.

With ticket prices so high, the teams are naturally more vigilant. One stadium employee said the Eagles now employ the equivalent of secret shoppers to try to ensure their own employees are on the up-and-up. They use ticket scanners at Penn.

Don't bother trying the behind-the-scoreboard window anymore at the Palestra. There's a video screen there now and the space behind it is gone.

A far cry from the old days, Harrell said. In those days, a guy could become a neighborhood hall-of-famer with his ingenuity at "getting in."

"There was this guy - we called him 'Tex' because he used to ride a horse through Southwest Philly when he was a kid. He used to own a bar called Tex's Tavern," Harrell said. "The Phillies won the World Series in 1980, right? Nobody could get tickets.

"So we're watching the game. This is the World Series. And sitting right next to Pete Rose and all the rest of them was a maintenance man with a big push broom."

As legend had it - and still has it - the man with the broom was Tex, working stadium maintenance for the only day of his life.

"Tex swept into Veterans Stadium," Harrell said, "and he sat in the dugout - next to a cop."