Years later, teacher keeps close ties with former students

Five grew up on the hard streets of North Philadelphia, one in the killing fields of Cambodia. Two are social workers, one is a nurse, another a soldier who served two tours in Iraq.

Five grew up on the hard streets of North Philadelphia, one in the killing fields of Cambodia.

Two are social workers, one is a nurse, another a soldier who served two tours in Iraq.

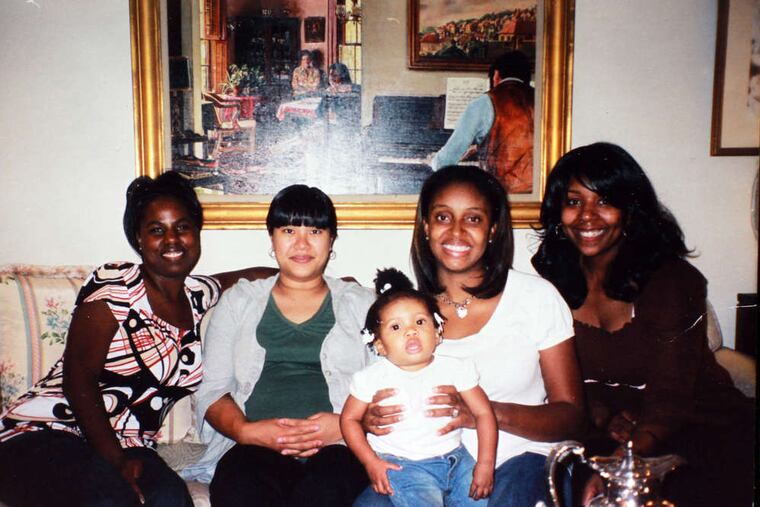

They are black, Latino, and Asian, all about the same age, all but two of them mothers, all bound to one another today through the happenstance of having long ago shared a particular middle-school teacher. Their intergenerational, multiracial friendship might be unusual in parts of the Philadelphia region, recently named among the nation's most segregated, but it thrives at Caryl Levin's house in Melrose Park.

It's a precious thing, Levin says, to see former students make their way through life, to see them raise families, to choose and sometimes struggle with their choices, whether those be in men or careers. To have a connection that mattered then and matters now.

On May 29, they'll gather on Stratford Avenue as they do twice a year, a group of women upon whom time has worked its magic and taken its toll. It's not a reunion - they're too close and too in touch to call it that. It's more an affirmation, with the 70-year-old Levin as its gravitational center.

"We love her," said Zaccheau Chamberlain-Milice, 35, a supervisor at the Philadelphia Corp. for Aging. "Some of us, we look at her as a mother figure. We have parents, but they may not have been the strongest at the time we needed them. We could talk to Mrs. Levin."

"A different world"

Levin spent 26 years in the Philadelphia public schools, most of them teaching social studies at Cooke Middle School, at Old York Road and Louden Street.

The school generally was caring. The neighborhood generally was not.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Levin said, several students stood out not only for their intelligence but for their determination to succeed, to not be brought down by the streets. Any of them could have ended up a statistic. Instead, all but one have a college degree.

"She opened us up to a different world," said Anitra Billington, 34, once Levin's seventh-grade American history student, now a social worker and University of Pittsburgh graduate.

Levin took her students to visit historic sites, not just read about them, Billington said. And afterward, instead of writing a report, students might be asked to write a poem.

As a child, Billington's home life could be chaotic. Today she works with parents who have lost custody of their children and seek reunification. She also serves as a mentor to children - passing on some of what Levin did for her, she said.

Growing up, Chamberlain-Milice lost two siblings to homicide and a third to prison. She earned a bachelor's degree at Lincoln University, a master's at the University of Phoenix.

Schere McCottry Hill had her first child as a teenager. She earned a college degree and is now a nurse.

Phom Phau Tann Owens escaped from Cambodia with her uncle and sister, landing in North Philadelphia. She graduated from college and lives in Atlanta.

Mai McMenamin grew up as one of 11 children in a family that emigrated from Vietnam. She graduated from Temple University, and is a mother of two with a third on the way.

Levin said she wasn't expressly friends with them in middle school - teachers can't be equals with young students. But she cared about them, and they about her. In 1992, she left Cooke for the World Affairs Council, working to organize educational after-school programs and speakers.

A couple of her former students started showing up. They brought others. In 1996, Levin took a job teaching at Fels High School in Northeast Philadelphia. As time went on, a group of former students solidified, all women of color, all of the city, all ringed around a white Jewish woman from the suburbs.

"The magic in all of it is Miss Levin," said Tania Herrera, a soldier stationed at Fort Bragg, N.C. "She has the same enthusiasm and excitement every time she sees you. She's so unbelievably interested in what you're doing, and how you're turning out."

In Levin's history class at Fels, Herrera said, she was inspired to consider her own perceptions of world events. The Army offered a chance to participate in history, not only to learn about it. Now 33, she's about to be medically retired, suffering from traumatic brain injury, post-traumatic stress disorder, and a bad shoulder.

She isn't sure what's next. She knows Levin will help her figure it out.

"It's a really special friendship for me. It changed my life," Herrera said. "When I walk away from her, I feel like I could be president of the United States. She makes you feel like there's nothing in this world you can't do."

A full and noisy house

Not everyone can make it to dinner this month, with Herrera in North Carolina and Owens in Georgia. The others will bring husbands and children, ensuring a full and noisy house. There'll be no pizza or take-out. Levin always cooks.

She'll also offer her former students what she's always offered: An ear. A heart. A more experienced perspective on life and its challenges.

"Each one of these kids, they're amazing," Levin said. "They did it themselves. I didn't change their lives. They changed it themselves."