The Phantom Bomber's escape into the shadows

The back-to-school party called for costumes, so Trent University students came as ghosts and witches, moving in and out of the redbrick rooming house at 283 W. King St. in Peterborough, Ontario, all night.

Last of two parts

(Find the first part here)

The back-to-school party called for costumes, so Trent University students came as ghosts and witches, moving in and out of the redbrick rooming house at 283 W. King St. in Peterborough, Ontario, all night.

That complicated the task for Canadian police staking out the place.

Two men on the FBI's 10 Most Wanted List, suspects from the deadly University of Wisconsin bombing 11 days earlier, had been tracked to the corner house in Peterborough, 65 miles northwest of Toronto.

Local police wanted to raid the Sept. 4, 1970, party, but their Royal Canadian Mounted Police counterparts wouldn't act until authorized by their superiors.

As he waited at police headquarters, Peterborough Inspector Bob Lewis contacted the lead Mountie at the scene.

"[He] reported the only activity had been some kind of commotion in front of the residence well after midnight," Lewis recalled.

Fearing the ruckus may have been cover for an escape, Lewis phoned the boardinghouse manager - an informant who earlier had identified photos of Leo Burt and David Fine.

"You can imagine my dismay," said Lewis, now retired in Peterborough, "when the informant reported the suspects were no longer there."

Burt and Fine had leaped out a rear window, so hurriedly they'd left behind their wallets. A Social Security card suggested Burt had been using an alias, Eugene Donald Fieldston.

It would take authorities six more years to capture Fine. They would never again get so close to Leo Burt.

Vietnam's tumult radicalized many young Americans. Few would travel as far to the antiwar extremes as Burt, a 22-year-old former Boy Scout from Havertown. And of all those who did - who committed an act of violence in the name of peace - Burt is one of the last to escape punishment.

Burt, who went to the University of Wisconsin for the rowing and gravitated instead to its radical politics, has been sought by the FBI for 44 years, since J. Edgar Hoover was the bureau's director.

Leo Burt could be here or abroad. He could be alive or dead. He could be lucky or smart. All authorities know for sure is that he has eluded their grasp.

Lighting the fuse

Less than two weeks before his Canadian escape, it was Burt who was conducting middle-of-the-night surveillance.

On Aug. 24, he and Karl Armstrong, a 24-year-old antiwar activist in Madison, were sitting in a stolen van outside the University of Wisconsin's Sterling Hall.

It was almost 3:35 a.m. and their vehicle was packed with a bomb weighing nearly 2,000 pounds.

Their target: the Army Mathematics Research Center (AMRC) on Sterling Hall's fourth floor.

After lighting what Armstrong said was a six-minute fuse, the two men sprinted toward a Corvair driven by Armstrong's brother, Dwight. As they passed a nearby phone booth, they signaled to Fine, who called Madison police. The night dispatcher, Sgt. R.G. Birencott, answered. The FBI recovered the conversation.

"OK, pigs, now listen and listen good," Fine said. "There's a bomb in the Army Math Research Center, the university, set to go off in five minutes. Clear the building. Get everyone out. Warn the hospital. This is no bullshit, man!"

Fine jumped in the Corvair and they sped off. Less than two blocks away they heard and felt the enormous blast. A fireball rose over campus, followed by a debris-filled cloud.

"My wife and I were living in student housing close to campus," recalled Grant Johnson, now an assistant U.S. attorney in Madison. "And we were lifted literally out of bed."

Amid the chaos, a campus policeman noticed a fleeing Corvair. Soon an all-points bulletin was issued.

Driving north, the bombers listened on the radio for news. They learned the explosion killed a researcher, Robert Fassnacht, a 33-year-old physicist and father of three young children.

At that moment, Karl Armstrong would tell authorities, Burt broke down sobbing. But soon, according to what Dwight Armstrong told former Los Angeles Times editor Tom Bates for his 1992 book on the bombing, Rads, Burt's resolve returned.

Bates writes: "He's cold as . . . steel," thought Dwight.

Pulled over

That Leo Burt has been at large for 41/2 decades is even more remarkable when you consider police stopped him within an hour of the crime.

Leaving Madison, the foursome headed toward Devil's Lake, a remote and popular camping area not far from the Baraboo Army munitions plant that Karl and Dwight Armstrong tried to bomb from a stolen plane that January.

A Sauk County sheriff's department officer, Sgt. Bob Frank, spotted the Corvair and pulled it over. Frank wondered what four kids from Madison were doing in the middle of nowhere in the middle of the night.

They explained they were going camping. The officer thought that one of the passengers, Burt, had been crying.

"I just graduated," Burt explained, "and I'm going back to Philly tomorrow."

After a check with Madison police turned up only a shoplifting charge against Fine, they were allowed to go.

Shaken, the four split up. The two East Coasters, Burt and Fine, headed for Manhattan.

"We are in New York with good contacts ready to head for Canada," Fine wrote to a mutual college friend and Cardinal staffer, Elliot Silberberg, in a letter the FBI discovered in trash outside Fine's Spaight Street rooming house.

(Silberberg declined to be interviewed by The Inquirer, but in his e-mailed refusal he urged a reporter to "discuss Leo in the context of those times, and note that the Sterling Hall bombing came not long after the horror of Kent State.")

While lying low in New York, Burt sent a letter home, telling his parents that, having graduated, he was seeking a journalism job there. He asked them to save newspaper clippings of a Schuylkill rowing event and casually mentioned the bombing.

"Did you hear about that explosion at Wisconsin? I didn't get to see it, but you could hear it far away, even when sleeping."

He signed it "LEO, /now BACHELOR OF ARTS."

Burt also completed a post-bombing manifesto he would mail to the Kaleidoscope, a counterculture newspaper in Madison.

"THE DESTRUCTION OF AMRC WAS NOT AN ISOLATED ACT BY 'LUNATICS,' " he began. Burt's strident tone and use of capitals would later lead agents to suspect he might be the Unabomber, before Ted Kaczynski was apprehended in 1996.

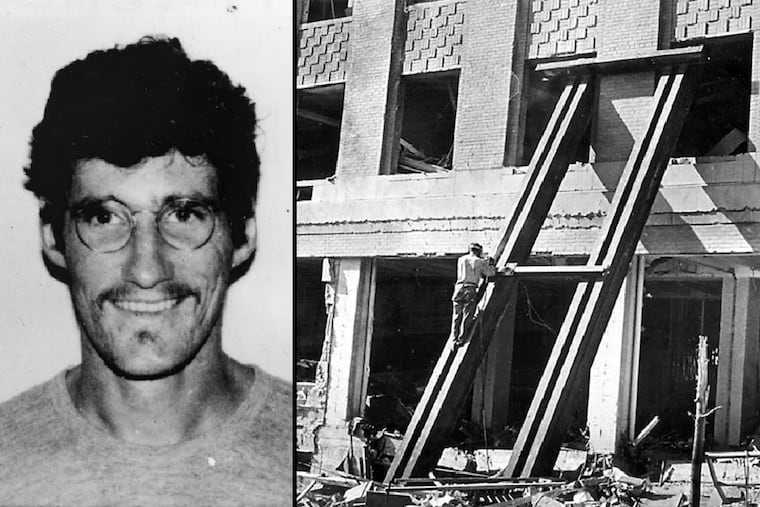

The AMRC, isolated on an upper floor, had not been destroyed. But much of Sterling Hall had, including the physics department, research labs, and a rare and valuable particle accelerator.

Fassnacht, a postdoctoral student working on a superconductivity experiment in the basement, was found dead, facedown in a foot of water. The other occupants, two researchers and a security guard, had been badly injured.

Thirty other campus structures were damaged, as were homes and businesses in a wide radius. Three blocks away, on the roof of an eight-story building, investigators found a chunk of the stolen van.

The bombers still hadn't been publicly identified on Aug. 29 when Burt, eager to get to Canada, telephoned Paul Bracken. He asked his close friend from Monsignor Bonner High School if he could drive him and Fine that night to Boston, where they'd stay with Fine's sister.

Bracken, a Columbia engineering student home for the summer in Upper Darby, agreed and arranged to meet Burt in Manhattan at Columbia's bell tower. Since Bob Beaty, a mutual friend and fellow rower, had a reliable car, a 1964 Impala, Bracken asked him not only to come along, but to drive.

(Now a Yale political science and business professor and a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, Bracken also declined to be interviewed by The Inquirer. "I really have nothing new to add to what's out there," he said by e-mail. He and Beaty would be questioned several times by the FBI and again before a Madison grand jury.)

On their ride to New York, Bracken and Beaty, by then a discharged and disillusioned Marine, talked about their old friend. They wondered if Burt had been involved in the Wisconsin bombing.

Asked why they made that connection, Beaty said: "It was just a sign of the times."

Did Burt mention the bombing on the trip?

"I would say 'No comment' on that," Beaty said.

In Rads, Bates wrote that the two friends half-jokingly asked Burt if he was one of the bombers.

Bates writes: "Yeah, I lit the fuse," Leo crowed. They laughed with him, but a little nervously.

Arriving in New York about 8 p.m., the travelers found Burt, wearing sunglasses, on a bench near the bell tower. They drank a beer, rendezvoused with Fine, and soon left for Boston.

Neither Bracken nor Beaty would see Burt again.

One of the subsequent visits from the FBI came at a Manayunk boathouse that was a hangout for rowers.

"This was right after and the FBI was pretty hot on everybody," Beaty recalled. "They wanted to come down to the boathouse and meet everybody. The night before, the place got vandalized. Somebody tore up the American flag and wrote swastikas and graffiti all over the walls. We were in the midst of cleaning it up when the FBI came in. You can imagine what they thought."

'A big explosion'

On the night of the bombing, Kent Miller was a clerk working the overnight shift at the FBI's Oklahoma City office. He was on the phone with an agent in Milwaukee.

"Got to go," the agent told Miller. "There's been a big explosion in Madison."

That explosion triggered one of the lengthiest manhunts in FBI history. Miller, who would rise to special agent, had no idea then that he'd spend much of his career on it. He pursued Burt through the 1990s, after other agents such as George Baxtrum, Alan Thompson, and Chris Cole had moved on.

Someone was always seeing Leo Burt somewhere. Perhaps the most promising sighting for Miller was at a Denver homeless shelter, where a mysterious resident who resembled Burt would disappear for days, then return.

"We managed to get his prints on a soda can," Miller said. "They didn't match."

At various times, Miller enlisted in the hunt the FBI's Joint Terrorism Task Force, Interpol, and the bureau's overseas legal attachés.

The FBI placed Burt's photo in fitness magazines, in left-wing journals (a letter allegedly written by the fugitive had appeared in Liberation in 1972), and in publications popular with African Americans, believing the Black Panthers might be abetting the fugitive.

Today, investigators surmise Burt may be living quietly and lawfully in North America. He's almost certainly never been fingerprinted.

Most believe Burt is alive, but at least one thinks he may have killed himself, wracked with remorse after the unanticipated death of Fassnacht.

Then there's the theory floated by many who have followed his case - that Burt was an FBI informant.

"There's absolutely no evidence of that," Miller said. "Having worked for the government for so long, I don't see how a secret like that could be kept."

Also, he added, none of the other bombers raised the possibility of entrapment in their defenses.

Those three men each served from three to seven years in prison. They were sentenced in a different era, after President Jimmy Carter had granted amnesty to draft-evaders and when sympathy with protesters remained strong.

If such leniency ever tempted Burt to surrender, the post-9/11 atmosphere likely disabused him of that notion. In today's world, agents note, there's far less tolerance for violent political acts, no matter how one might justify them.

"Today, if there's a bombing that kills someone, that person would never see freedom again," said Kevin Cassidy, the Madison-based FBI agent now charged with finding Burt.

'I remember him'

At August's 2014 Canadian Henley in St. Catharines, Ontario, thousands of rowers swarmed Lake Ontario's shores. Some of them were old enough to be Leo Burt. Some knew his story.

"Sure, I remember him," said Patrick Anderson, 65, from Toronto. "Someone in our sport does something like that, you don't forget."

If FBI agents were present during the weeklong event, as they had been in numerous years since 1970, they were indistinguishable from the crowd.

Again and again, the search for Burt has returned to his rowing roots.

"We talked to rowers who knew him and those who didn't," Miller said. "Nothing panned out."

On Boathouse Row, where he spent so many days in high school and during college summers, Burt's presence still hovers.

"Nobody talks in the past tense about Leo," said Mike Cipollone, a longtime friend from Havertown and a rowing companion who would later become a crew coach at Bonner.

Some don't talk at all.

"Anyone who actually knew Leo clams up when asked about him," said Mike Bowers, who rowed with and against Burt.

Ten years ago, Cipollone's Bonner crew was raising money. For $200, sponsors could get their names etched into an oar. A whimsical Father Judge alum had "Leo Burt" inscribed on one.

Rumors persist that some Philadelphia rowers have spotted Burt at various events. Some of those whispers reached the FBI, some did not.

The FBI acknowledges having used unspecified "investigative techniques" to monitor not only Burt's rowing friends but his family.

Agents staked out the 1986 and 1993 funerals for his parents, who are buried across the street from his boyhood home. Burt, they insist, has made no contact with anyone from his past.

"We'd have known," Miller said. "He's just been incredibly disciplined. He's basically given up his life."

Realizing that in late middle age, Burt no longer resembled his wanted-poster photo, Miller ordered a computer-aged image.

"We needed to get pictures of his male family members," he said. "We got one of his dad, a brother, an uncle who was a priest. His dad was obviously elderly and becoming frail, but he cooperated."

Howard Burt, who died in 1993, never spoke publicly about his son. A few months after the bombing, Burt's stepmother, May, who passed away in 1986, talked to Philadelphia Bulletin columnist Sandy Grady.

"I can't picture it in my mind," she said of her stepson's involvement. "He would never have hurt anyone. That's why he wanted out of the draft. There's a piece missing."

Grady, too, tried to make sense of Burt's unlikely transformation.

"What tidal waves pull at the straight, solid ones like Leo Burt? It is a riddle that goes to the heart of America, 1970."

Smoothie stand

Karl Armstrong was captured in Toronto in 1972, and his brother Dwight was apprehended in the same city five years later. Agents found Fine in San Rafael, Calif., in 1976.

Represented by activist attorney William Kunstler, Karl Armstrong served seven years of a 23-year sentence. Dwight Armstrong, who died of cancer in 2010, and Fine both were sentenced to seven years and released after three.

Dwight Armstrong would be jailed again on Indiana drug charges. Karl Armstrong returned to Madison. He operated a popular on-campus beverage cart, Loose Juice, and later opened a deli called Radical Rye.

"Late one Friday, I fly back to Madison," said Johnson, the assistant U.S. attorney. "I get in a cab and I happen to look at the driver's picture. It was a smiling Karl Armstrong. I'd go to his smoothie stand and think: 'This is a great country. All that was wrong in 1970 and now Karl Armstrong is a thriving capitalist.' "

Now 68 and retired, Karl Armstrong spoke only briefly with The Inquirer, stating as he often has that while he regrets the death and injuries the bombing caused, he continues to believe it was justified.

"Think about what was going on Vietnam," he said. "Anything that might have led to that war's end would have been a good thing. We just should have been more responsible [in setting off the bomb]."

Asked about Burt, a hint of a smile crossed his wide face.

"I hope Leo's still out there," he said. "If I saw him, I'd tell him he's done a heck of a job staying free."

After their capture, the men were questioned about Burt. Fine was "completely uncooperative," Miller said, while the Armstrongs seemed to harbor some resentment.

"I got the impression Dwight and Karl felt abandoned by Leo," he said. "They felt he had more contacts and more ability to escape and left them to their own devices."

Who those contacts might have been is a matter of speculation. As a student journalist, Burt got to know Black Panthers, SDS members, and many others in the radical left. It wouldn't have been hard, the FBI notes, to find counterparts in New York, California, or Toronto.

Fassnacht's family, meanwhile, long ago forgave the bombers, even suggesting authorities consider amnesty for Burt. A plaque memorializing the victim was placed on the rebuilt Sterling Hall in 2007. His two daughters graduated from Wisconsin. His son is a physics professor in California.

And still the search for Burt continues.

"We thought at some point he might say, 'Let's get this over with' and give up," said Cassidy, the FBI agent. "But until then we'll keep looking."

In 2010, the bombing's 40th anniversary, the FBI recirculated the wanted poster, which now contained the updated images of the fugitive, and reemphasized the $150,000 reward.

Ironically, the crime probably hastened the end of the antiwar activism its perpetrators had hoped to encourage. Nonviolent protest was one thing, a truck bomb something else.

"When the students came back to school that September, the life was sucked out of the movement," said Paul Soglin, a onetime University of Wisconsin activist and now the mayor of Madison.

Not long ago, Cipollone and some friends were discussing Philadelphia's rich rowing history at a Boathouse Row bar.

"We're all talking about what a great sport it is and somebody said, 'You know, nobody ever goes bad in rowing.' There was this long pause before this one older guy says, 'Leo Burt did.' "