Mystery of Vietnam War's 'Little Ty' may be solved

On a bunk aboard the troop ship that took him to Vietnam, a soldier called "Little Ty" scrawled a message of hope and home.

On a bunk aboard the troop ship that took him to Vietnam, a soldier called "Little Ty" scrawled a message of hope and home.

"See ya at the Blue Sal!" he wrote in August 1967, promising to return to North Philadelphia after a year at war.

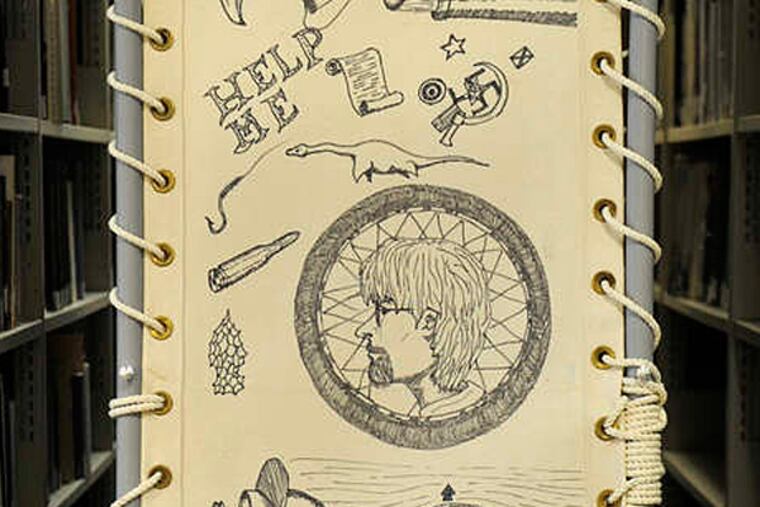

Ty's canvas rack is now at the Smithsonian, part of the institution's military collection, and a photograph of it is on display at the Independence Seaport Museum in an exhibition of Vietnam-era graffiti. But despite a decade of periodic searches by historians, journalists, and even a Philadelphia detective, Little Ty's identity has remained a mystery.

Until, perhaps, now.

For the first time, people seeking to solve a 45-year-old enigma from the Vietnam War have identified a soldier they believe to be Little Ty. The evidence is compelling, if not ironclad, based on connections revealed within a three-state web of military records, ship rosters, and property deeds.

A key development: A Virginia researcher's discovery that his archive held records naming the soldiers aboard ship when Little Ty wrote his note, documents not even the National Archives possessed.

Those rosters show that among the 2,568 men on the Gen. Nelson M. Walker on that voyage, only one was named Tyrone - Army Pvt. Tyrone R. Parler, service number RA15757634, of the 610th Engineer Company.

He entered the service from Philadelphia and returned there after the war, living in a house on North 12th Street, according to military records and other documents The Inquirer has obtained.

The records also show that the Aug. 12 date on the canvas has special significance: The message predicting a happy Philadelphia homecoming was written on Tyrone Parler's birthday.

Art Beltrone, the Virginia military historian who first discovered the scribbles and notes left by Vietnam-bound troops, and who found the troop rosters within his own large Vietnam collection, believes Little Ty has finally been identified.

"It's wonderful," he said from his home in Keswick, Va. "It's become a mission."

Social Security records indicate Parler, 70, is still alive.

Parler's last known address was 6708 N. 12th St., in East Oak Lane. A woman who answered a reporter's knock on the door said she didn't know Parler, and a neighbor said the family left long ago. Parler's listed phone number now belongs to someone else.

It's clear he was aboard the Walker when it departed Oakland, Calif., on Aug. 10, 1967. At that time, the era of big troop ships was ending. But when the Pentagon needed to deploy large numbers of men, or move entire units together, it used traditional troop ships like the Walker, which could carry up to 5,000.

The journeys were long, slow, and stressful, with soldiers suspended between home and war. A man lying on his back had 18 inches from his nose to the bunk above, and three weeks to think about what lay ahead. Hundreds of men wrote notes of fear, bravado, and longing.

Beltrone discovered the canvases in the late 1990s, when, as a consultant to The Thin Red Line, the Sean Penn movie, he clambered aboard the Walker.

The scribbles and drawings - some are full-scale artworks - now form the heart of Beltrone's Vietnam Graffiti Project, which has spawned a book, website, and traveling exhibition.

From the start, Little Ty's note ranked among the most intriguing. It was his optimism, his certainty that he would survive and return to Philadelphia.

"Little Ty from 1-2 Poplar St. TenderLions, North Philly, slept here on his way to the war," Ty wrote, marking the date as Aug. 12, 1967. "Will be back Aug. 1968. See you at the Blue Sal!"

John Buchanan believes the "Blue Sal" was a bar or meeting place. Now retired after 25 years as a detective in the Philadelphia District Attorney's Office, he recognized "TenderLions" as the name of a street gang, and "1-2 Poplar" as lingo for 12th and Poplar Streets.

His own searches for Ty came to naught.

But Ty's clues - an address, a neighborhood, a date - offered hope the mystery could be solved by locating a roster of the troops on that sailing.

The Navy searched its files at The Inquirer's request, but found nothing. The National Archives came up empty, too.

This fall, the Seaport Museum opened "Marking Time: The Voyage to Vietnam," featuring canvases marked by men from the Philadelphia area. This month, amid publicity for the exhibit, and specifically around Little Ty, Beltrone decided to reexamine his Walker holdings - hundreds of documents, letters, photographs, questionnaires, newspapers, and recordings.

He realized that during the previous 20 years, servicemen who were aboard the ship in August 1967 had sent him complete rosters of their units.

"I'd forgotten about them," Beltrone said.

Military records show Parler joined the service in Philadelphia; voting, property, and legal records show him living in the city after the war.

Parler owned the 12th Street house with his mother, Helen Giddings, and sold it to her for $1 in 1997. He remained on city voting rolls through 2000, the documents confirming his birthday as Aug. 12, 1944. He turned 23 aboard the Walker.

Trying to identify a soldier from a nickname is an arduous, nearly impossible task, archivists say, made more complex by certain characteristics of the Vietnam War.

Soldiers often referred to one another by nicknames, knowing even close friends only as "Ace" or "Bigfoot." Because combat tours lasted a year, not the duration of the war as in earlier conflicts, men came and went, limiting their time with one another.

Later, the war's unpopularity dissuaded men from joining veterans groups or holding reunions, further dulling ties and memories.

"My company, we didn't get together for 25 years after most of us had served," said Terry Williamson, a Marine infantry officer in Vietnam and now president of the Philadelphia Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund. "To this day, there are people I would love to see, but I just wouldn't know how to get in touch with them."

The 610th Engineers, with Parler among them, disembarked from the Walker under a rainy, cloudy sky at Cam Ranh Bay, according to a unit history. The mission was to provide construction and road-building support.

Parler served in the company's 87th battalion as a supply specialist, responsible for maintaining and storing equipment.

He was in the Army from April 1966 to April 1972, according to military records. He attained the rank of Specialist 5 by the time he was discharged.

"Way back when," Beltrone said, recalling the start of the search for Ty, "we thought we'd really like to know who this guy was."

The next job, he noted, is to find him.

215-854-4906 @JeffGammage