Prep seminary closes in Chicago

CHICAGO - For more than a century, Archbishop Quigley Preparatory Seminary has prepared teenage boys for the priesthood, largely unchanged as the city around it was transformed from gritty industrial center to modern metropolis.

CHICAGO - For more than a century, Archbishop Quigley Preparatory Seminary has prepared teenage boys for the priesthood, largely unchanged as the city around it was transformed from gritty industrial center to modern metropolis.

But another kind of change finally caught up with Quigley.

The 102-year-old seminary - a Gothic-style building in a tony shopping district - closed recently because of a shrinking student body that has seen just one of its 3,000 graduates ordained in the last 17 years.

Roman Catholic preparatory seminaries have all but vanished in the United States, highlighting the church's struggle to find men willing to dedicate themselves to the celibate priesthood.

"This is more or less the final nail in the coffin of the preparatory seminary," said R. Scott Appleby, a historian at the University of Notre Dame who has written extensively about the church.

"Historians of the Catholic Church will point to the closing of Quigley . . . as a final landmark in a trend that has been building now for almost 50 years."

As recently as the late 1960s, there were 122 high school seminaries in the United States with a combined student body of nearly 16,000 boys, according to the Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate at Georgetown University.

Quigley, which counts New York Cardinal Edward Egan and Atlanta Archbishop Wilton Gregory among its alumni, was bursting with about 1,300 students in the 1950s; it had just 183 at the beginning of this school year. When Archdiocese of Chicago officials announced in September that the school would close, they said it would be $1 million in debt by June.

Its closure will leave just seven preparatory seminaries, with a combined enrollment of about 500 students, in the United States. The number of priests in the United States has dropped from nearly 59,000 in 1975 to about 42,000 last year.

The decline of high school seminaries illustrates a dramatic shift in the way the church finds priests - and how it has had to scramble to do so.

Parishes increasingly are being served by priests from foreign countries, in large part because fewer American men are becoming priests. At the same time, the average age of new priests is older, with many men waiting until their 30s, 40s and beyond.

When 13 priests were ordained last month in Chicago, all but one was born and raised in another country, with most attending college before they came to the United States. Nine were in their 30s. The lone American-born priest was a 42-year-old former advertising executive.

The reasons for the shift begin with how dramatically things have changed since Quigley opened in 1905.

Like other seminaries, Quigley, which moved to its present home in 1918, thrived because large Catholic families, many Irish or Polish, often sent at least one of their sons there.

"In the old days, you had an Irish family with three kids. One was going to be a priest, one was going to be a cop and one was going to be a fireman, and the mother was going to be the one who decided which was which," said Peter Makrinski, a longtime teacher and coach at Quigley.

That began to change in the 1960s and '70s. Archdiocesean spokesman James Accurso said seminaries fell out of favor among young people for the same reason marrying right out of high school did.

"A lot of things in life are delayed. Young people get married later, and I think they join the priesthood later," he said.

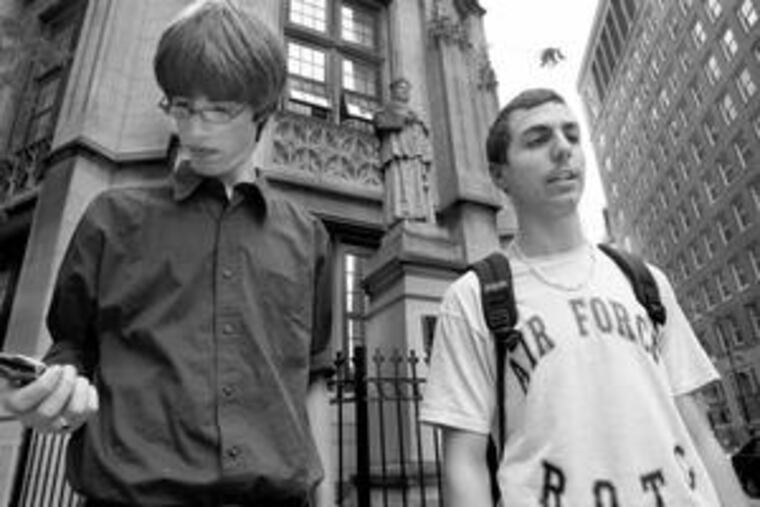

Morgan Mellske, an 18-year-old Quigley senior, said that although some students there are considering becoming priests, most are not.

"I don't even know what I want to do with the rest of my life," said Mellske. "People become priests in the middle of their life."

Appleby, the historian, said there's more to it.

"It's a culture that raises a collective eyebrow at the notion of a young man or a young woman [who] would renounce sexuality or sexual self-expression," he said. "There's a general skepticism about the emotional health of people who would do that voluntarily," particularly at such a young age, he said.

Within the church itself, more people began questioning the wisdom of training teenagers to become priests and forgo sex.

"Our understanding [of sexuality] is more developed today," explained the Rev. Donald Cozzens, a professor at John Carroll University in Cleveland and a former seminary rector who criticized mandatory celibacy in a book, Freeing Celibacy.

Even families that continued to send their sons to Quigley made it clear they were doing so for a Catholic education and not to start them on a path to the priesthood.

"The parents, they want their sons to make money; they want their sons to get married," Makrinski said. "They'd say, 'I'd much rather see them get a job.' "