A natural for autoharp

The plan was that neither one would buy the other a gift. But Nancy Stiles violated that deal, and on their sixth wedding anniversary, back in 1976, she gave her husband, Ivan, an autoharp. He was surprised. The stringed folk instrument was not something he coveted.

The plan was that neither one would buy the other a gift. But Nancy Stiles violated that deal, and on their sixth wedding anniversary, back in 1976, she gave her husband, Ivan, an autoharp.

He was surprised. The stringed folk instrument was not something he coveted.

"Until then, my only connection with the autoharp was in eighth grade," Stiles recalls. "One got passed around in class, and everyone tried a few strums."

Stiles bought an instruction book and began learning to play his new toy. He was soon charmed by its simplicity and versatility, the variety of music he could produce. After several months of practice, he decided he needed a teacher.

He auditioned before a prospective teacher at a music store in Lafayette Hill, but the teacher cut the session short. "There's nothing I can teach you," he said. "You should be teaching the autoharp yourself."

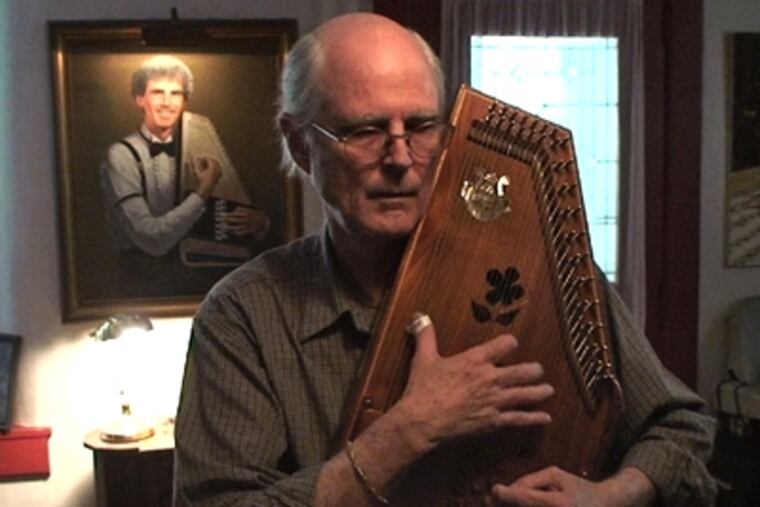

It was an early indication of Stiles' peculiar musical genius. Today, at age 63, Francis Ivanhoe Stiles is an international autoharp champion.

"Nothing else really sounds like it," says Stiles, who lives in an early 19th-century house on a bend in the Pickering Creek near Phoenixville, Chester County. "You don't just play chords. You can strum it and pick it. You can play all kinds of music, from traditional to contemporary."

The other day, Stiles, a slender man with fine features and a gentlemanly, soft-spoken manner, performed "Home Sweet Home" on one of his half-dozen autoharps, producing an ethereal sound that seemed a blend of guitar, banjo, fiddle and harp.

"He's one of the greatest autoharp players on the planet," says Adam Miller, a folk singer and fellow autoharp player who lives in Drain, Ore. "He has a wonderful lighthanded touch and a very recognizable style that is uniquely his own. He gets stuff out of an autoharp no one else can."

Stiles' passion for the autoharp kindled an interest in other folk instruments with ancient pedigrees: the Appalachian dulcimer, the bowed psaltery, the hurdy-gurdy, and the musical saw. Over the past 30 years, Stiles, a musical polymath with an antiquarian bent, has delighted in mastering them all.

"You don't have to be the best, because they're all so weird people just enjoy listening to them," Stiles says.

On the second-floor porch he uses as his study, Stiles stroked two bows across the strings of a psaltery, whose roots run deep into the Middle Ages. From it, seemingly by magic, he conjured the melody of the Shaker hymn "Simple Gifts," rendered all the more sweet and affecting by the otherworldly tone of the instrument.

"I like things in my life to be simple," said Stiles, explaining his fondness for the psaltery and similar musical relics, including a recently acquired pump organ in the parlor.

Paradoxically, Stiles is flummoxed by more conventional instruments, such as the guitar, banjo and mandolin, which strike him as awkward. He has little formal training and plays mostly by ear.

"I never had any music theory," he says. "I just learned what I needed to learn. I have a limited number of brain cells, and I'm losing them fast."

While the blood of artists flows through his veins (his maternal grandparents were painters, educated at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts), Stiles also is blessed with musical talent. It became apparent in eighth grade when he began piano lessons at a Catholic school in south Dade County, Fla., where he grew up. He showed up for his first lesson with the music he intended to play: the first movement of Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata. The nun, amused though she was by his ambition, tethered him to the standard practice book. Secretly, Stiles toiled on the sonata. By assigning letters to each note, he eventually memorized his way through the entire piece, measure by measure. He later performed it in the concluding recital.

When he was 18, Stiles was lured north to Philadelphia by an elderly cousin who lived in Germantown. He got a job at Strawbridge & Clothier as a messenger in the advertising department. Within three years, he was promoted to illustrator. He later launched his own advertising and graphic-design firm, and he continues to do design and illustration work today.

Stiles began playing the autoharp professionally in 1980. His first gig: He was hired to serenade shoppers for three hours one Saturday in the linen department of the Strawbridge & Clothier store in Wilmington.

"I never looked up the whole time," Stiles says. "I had terrible stage fright."

Evidently, he soon conquered it. By the mid-'80s, he was performing regularly at fairs, festivals, coffeehouses, colleges, clubs, and a growing number of events that recognized the appeal of the autoharp, including the Mountain Laurel Autoharp Gathering, which he helped organize. (The gathering, the first and largest devoted to the autoharp, is taking place in Newport, Pa., about 25 miles northwest of Harrisburg, from today through Sunday.) For 15 years, he spent from four to six months touring. For 10 years, he was editor of the Autoharp Quarterly, a magazine he cofounded. A skillful and devoted teacher, he is the author of Jigs and Reels for the Autoharp and has produced four CD - three of autoharp music, one of the musical saw. In 2000, he was inducted into the Autoharp Hall of Fame.

"He can pick single strings and play more intricate melodies," says Mary Ann Johnston, editor of Autoharp Quarterly. "He can play things that are fast and have a lot of notes, such as "Stars and Stripes Forever," and he gets them all in there, picking a lot of individual strings.

"He not only plays the autoharp well but he presents it well. He makes it enjoyable for people. He transfers his enthusiasm to the people he's teaching or playing for," she said.

As an autoharp instructor, Stiles has done much to popularize the instrument, Johnston says. One indication: A decade years ago, only about 500 people subscribed to her magazine; today. circulation is about 2,500.

Stiles also is an autoharp scholar. After two years of research, he unraveled the real story of the instrument's origins. The putative inventor, Philadelphian Charles Zimmermann, actually stole the patented 1880 design from a German, Karl August Gutter of Saxony.

"He took Gutter's instrument, lock, stock and barrel," Stiles says.

Today, Stiles performs only three to five times a year. Good-natured about the less-than-whelming interest in his odd pursuits, he nonetheless admits to frustration that he's so rarely invited to play locally. "I have to travel hundreds of miles to get people to hear me," he laments, almost apologetically. "The autoharp is not taken seriously. It's not given the credit it deserves."

For those who know and love the autoharp, however, it's like "a preview of heaven," as the slogan on Stiles' autoharp gathering T-shirt proclaims.

"I can easily get lost in the music," Stiles says. "I sit down to play for 10 minutes, and an hour and a half goes by."

To Learn More

For more information about Ivan Stiles and his autoharp music, visit www.ivanstiles.com.

EndText