An early quest for equality on the diamond

In this excerpt from "Tasting Freedom," Octavius Catto and his band of brothers, after desegregating Philadelphia's streetcars, choose another field of battle - the baseball field.

In this excerpt from "Tasting Freedom," Octavius Catto and his band of brothers, after desegregating Philadelphia's streetcars, choose another field of battle - the baseball field.

Perhaps his first time batting a ball was with the Rev. Thomas Smyth's son Adger in Charleston, playing where no one would see a white boy playing with a colored boy. Or as an 11-year-old in Allentown, N.J., where his father preached and he attended a boys' academy.

Back then, when his legs could run all day, he could pick up a bat, hit a ball hard, and watch it touch the sky. The bat was a stick or a piece of a lumber; the ball a cork or a used bullet wrapped in an old sock, sometimes covered snugly with rubber strips from an ancient overshoe. Young Octavius Catto had the hand-eye coordination. His hands were brown, five-fingered baskets where the ball always landed. He could throw a ball clothesline straight. The white boys saw he could play.

Negro baseball exploded after the Civil War. Much more than just a growth in exercise or leisure, the tradition of fraternal, social, and service organizations was stretched now to include baseball clubs with their own officers, dues, meetings, and rules of conduct - one more example of the nation within a nation trying to grab on to an outcropping of white America. Baseball was a public exhibition of Negro equality in a time of optimism, a time of Reconstruction. They could play the same game as white men.

Clubs formed in Newark, N.J., Albany, N.Y., and Rockford, Ill. The Excelsior club was Philadelphia's first, coming together early in 1866. As the weather cooled, another local club formed.

The first full season of the Pythian Base Ball Club was in 1867. Catto was the captain.

Emergence of a pastime

By the 1850s, colleges were fielding teams, including clubs at Princeton and Harvard. Pitchers threw underhand. Players fielded barehanded, hurting palms and gnarling fingers.

The National Association of Base Ball Players formed in New York in 1857. The association changed baseball from a recreational outlet to a competitive endeavor with strict rules. A year later, crowds of 10,000 attended a series of three all-star games between Brooklyn and New York. Double plays were made. Runners stole bases. Umpires called strikes. And fans paid an admission fee for the first time.

Newspapers touted one game in 1859 as the first between colored teams, the Unknown club of Weeksville against the Monitor club. One paper described the match between the New York-area teams: "The dusky contestants enjoyed the game hugely, and, to use a common phrase, they 'did the thing genteely.' . . . All appeared to have a very jolly time, and the little pickaninnies laughed with the rest." The Unknowns became known with their 41-15 win.

Philadelphia's first active baseball season was 1860, with the first game on June 11. The Winona club, led by Elias Hicks Hayhurst, defeated the Equity team 39 to 21. Also in 1860, a group of young music lovers belonging to the Handel and Haydn Society formed a team, the Athletics.

Even as players traded bats for the muskets of war, baseball's popularity soared. The game had been a decidedly middle- and upper-class pursuit because those men could afford to leave work to play. But the war introduced baseball to soldiers who were poor and working class. Prisoner-of-war camps on both sides let captured men play.

Back home, the Brooklyn Atlantics, comprising mostly butchers, were considered the best team in the North. In Philadelphia, fewer young men were available to play. Fields at Eleventh and Wharton Streets and at Camac Woods in North Philadelphia lay empty.

But by 1863, players were coming home from the war, and newspapers began hiring men to write about baseball. They were called sports writers. People began wagering on games. Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Brooklyn, and Newark had more than one good team. Soon those clubs began traveling, with New York-area teams coming to Philadelphia, and Philadelphia teams returning the visit in road trips that writers called "invasions," as the language of war and baseball intertwined.

After the war, President Andrew Johnson showed how important the game was by inviting the champion Brooklyn Atlantics to the White House.

Auspicious debut season

A Midwest colored team of hotel and restaurant waiters would call itself the Blue Stockings for the color of their leggings. But the new colored team in Philadelphia took a scholarly leap back to ancient Greece and adorned itself with name of the games that led to the modern Olympics. Enter the Pythian Base Ball Club.

The Pythian leaders were players who understood Greek history. Catto and Jake White were the captain and secretary, respectively, of the team, which had a lineup full of their Banneker Literary Institute and Institute for Colored Youth friends. Four lineups, actually - O.V. was on the starting nine while Jake was third string.

The Pythians' maiden voyage was a 70-15 clubbing by the Albany Bachelor club in 1866. Yet by the following spring, the team was widely known and highly regarded.

In a colored community overwhelmingly poor, Pythian players were relatively well off. They could afford the club's annual $5 dues and met in a room at Liberty Hall on the same floor as the Equal Rights League. They worshiped at the best black churches. They were whiter than the rest of the city's Negro populace - more than two-thirds were mulatto, compared with the 25 percent mulatto in Philadelphia.

If you were erecting the structure that resembled the best of the colored community after the war, the Pythians were standing on the roof.

And now the season was finally ready to begin. The Pythian club had persuaded some Excelsior players to switch allegiances. On June 28, the opponent was the Excelsiors. Bad blood was a mild description of the relationship between the teams. Catto batted second and played second base. Leading off was John Cannon, the pitcher and the team's best player. White baseball clubs called him a "baseball wonder." The Excelsiors went down, 35-16, as did the L'Ouverture club in another June contest, 62-7. Out of the gate, the team was 2-0.

Secretaries of the Mutual and Alert baseball clubs in Washington corresponded with the Pythians to set up games in the summer. The time, place, date, and accommodations for the visiting team and umpires for the games were not the only important issues agreed on. These three colored clubs were polite and competitive with one another and shared a sense of what was really important - what happened after the contest. Catto's team could hit, field, and throw a soiree.

The first correspondence had come in April from George Johnson, secretary of the Mutual Base Ball Club in the nation's capital.

Johnson and Jake White arranged games in the two cities, a home-and-home series. The Mutual club would also play the Excelsiors while in Philadelphia, and the Pythians would play the Alert club while in Washington. The Alerts were a more talented squad than the Mutuals.

White wrote most of the letters responding to or offering challenges. But on June 30, still exultant after the game against the Excelsiors, Catto wrote a letter to the Alert captain to tie up loose ends for their forthcoming July 6 game in Philadelphia.

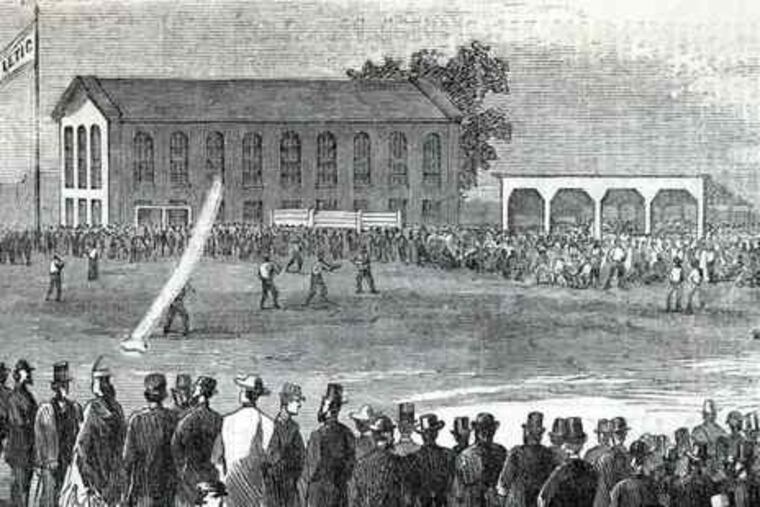

"As captain of the Pythian's Nine, it falls as my duty to address you . . . in reference to two points touching our forthcoming match. We have secured the grounds of the Athletic, and all of its conveniences (the best in the city) have been put at our disposal. I took the liberty . . . of securing the services of Mr. E. Hicks Hayhurst Esq of the Athletics' First Nine to act as umpire on the occasion."

Catto explained, "Mr. Hayhurst is considered the best umpire. . . . There is considerable interest and no little anxiety among the white fraternity concerning the game. . . . Yours very truly, O.V.C."

The Alert centerfielder was Catto's old friend Billy Wormley, now a rising figure among Washington's colored Republicans. Charles Remond Douglass, Frederick's son, played second base. These two teams were more than a collection of good ball players - they were elite young leaders of a race.

The Pythians won their third game, 23-21, with Catto scoring five times. The home team hosted a party and dinner afterward, providing 30 pounds of ham, claret by the gallon, ice cream, and a box of "segars." Jake White paid $78.26 from the team treasury for the feast, or about $1,200 in today's dollars.

In the fourth game, the Mutuals won a nail-biter, 44-43. The soiree afterward included ham and tongue.

The Pythians returned to Washington in the August heat for rematches. Big crowds watched, including white baseball players and colored leaders from each city. White reporters wrote that the teams were "a well-behaved, gentlemanly set of young fellows." Frederick Douglass sat in the stands and watched his son field "bounders," the term used then for ground balls.

The Pythians won both games, clobbering the Alerts, 52-25, and paying back the Mutuals with a 50-43 win that saw the Alerts' Charles Douglass serve as umpire.

From there on out, the 1867 club beat all comers, including the Resolutes from Camden. The year ended with a 9-1 record and acclaim as the best colored team in the city, and perhaps the nation. What more could it accomplish after one season?

The next big step

The Pythians' hierarchy was White; Catto; the club president, James W. Purnell; and the vice president, Raymond W. Burr - all of whom came out of abolition and Underground Railroad families.

Catto, now 28, had never been better known and had never felt more accomplished. Because of his status as a baseball player and captain, his name was familiar to Negroes throughout the Northeast. He had grabbed on to a handhold of justice by opening the streetcars.

But he kept reaching for another handhold. His team had played baseball as well as any white team. The next step was to play against white teams. To do that, the club had to do something no colored club had ever done - apply for membership in a state chapter of the National Amateur Association of Base Ball Players, the former National Association with the word amateur added because of a paying-for-players controversy. The state association was about to have its annual meeting in Harrisburg.

Colored teams were not welcome on some fields. On the Wharton Street field near the Moyamensing Prison, white men had lined Shippen Street to keep them out. The Pythians played there once in the 1867 season, but the trip was never made without anxiety and rarely without all four nines in attendance.

But now was the time to seek a change. It was October 1867. Negroes were being elected to office in the South. The Pythians had played on the field of the Athletics, an association member and the state's top team. Catto had come to know the Athletics' Hayhurst and had confided to him what they were going to do. Hayhurst and several more white ballplayers said they were on board. Catto asked Burr to attend the meeting for the club.

Insurmountable obstacle

When Burr arrived the night before the convention's opening, bad news greeted him. Hayhurst and D.D. Domer, the convention secretary, told him they had informally polled the delegates and the result was not good. "The majority of the delegates were opposed to it," Burr said.

Hayhurst and Domer didn't want a no vote on the record and asked Burr to withdraw the request so that the team wouldn't be "blackballed."

Burr refused. The credentials committee would spend the next day voting yea or nay on all the clubs seeking to join - including the Pythians' request. But there was still a chance for the colored club because Hayhurst was a committee member. While the credentials committee deliberated, white delegates sat in bunches talking about what the Pythians were trying to do. Burr, the only colored man in the room, listened, but the voices were too low to make out what they said.

The committee voted yea on 265 of 266 applications from clubs around the state. No one voted nay. They chose not to vote on the Pythians' request, perhaps out of courtesy to Hayhurst. That vote was moved to the next day.

Delegates went to Burr and assured him that the voting results were not their fault. They supported the Pythians, but they had to abide by their clubs' instructions to vote nay on a colored team's admission. Burr reported he was "treated with courtesy and respect." Someone gave him a free ticket to a baseball game the next day.

After the vote, delegates asked Burr once more to withdraw the application. He refused again. He "did not feel at liberty to do this whilst there was any hope whatever of admission."

He telegraphed home for instructions. Catto replied: "Fight if there was a chance."

Hayhurst arranged for the vote to be taken in the evening because he thought there would be more delegates then and a better chance for a Pythian victory. But once again, the committee chose not to vote on it. In the end, Burr withdrew the request and went home, having been given a free train ticket by one of the delegates.

A few days later, the Pythians played the Monrovians from Harrisburg and whipped them, 59-27. Catto, whose team had lost at the convention, hit a home run.

As for the color line in baseball, it would remain for another persistent second baseman to cross 80 years later.

Tuesday:

Violence and the Vote