Daniel Rubin: Remembering those who vanished with the S.S. Poet

Two women, two ways of marking inexplicable loss. Lotte Zukier-Fredette, 80, will drive on Oct. 24 from her Port Richmond rowhouse to Lewes, Del., then take the 11 a.m. ferry toward Cape May. She will make the trip alone, as she has done for the last 10 years.

Two women, two ways of marking inexplicable loss.

Lotte Zukier-Fredette, 80, will drive on Oct. 24 from her Port Richmond rowhouse to Lewes, Del., then take the 11 a.m. ferry toward Cape May. She will make the trip alone, as she has done for the last 10 years.

In the middle of the Delaware Bay, she will toss 34 roses into the sea and whisper something private to her Hansy, her son whom she last saw 30 years ago to the day, when his ship, the S.S. Poet, sailed into the Atlantic, then vanished without a trace.

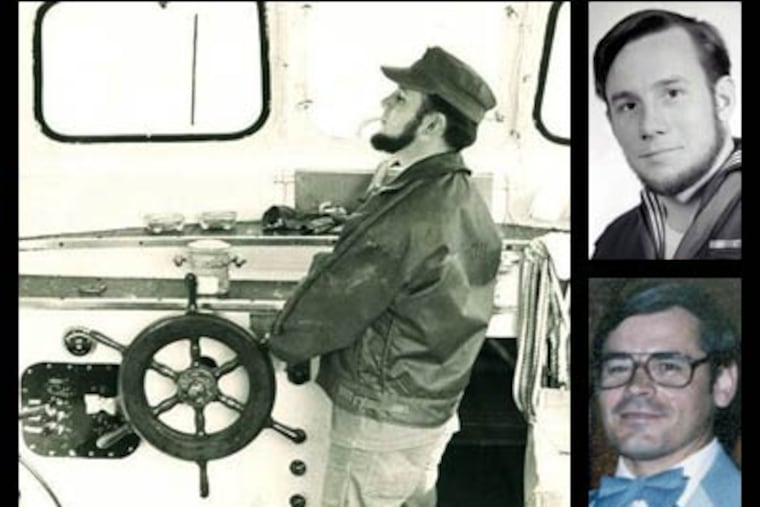

Hans Zukier was 32, an able seaman who had just celebrated the Phillies capturing their first World Series, when he signed on with a bulk carrier that was to deliver 13,500 tons of corn to Egypt.

Robert Pessek's 2000 book, The Poet Vanishes, describes a scene between mother and son.

"Hansy, that's a sardine can," she says as they approach the ship, driving along the pier. The look on his face is one of shock.

"Mom, I hope we don't step on each other.' "

Corn rains down on the car from leaks in the ship's hull. He grabs his seabag from the seat and finds his mouthwash has spilled onto his clothes.

"Hansy, all your clothes are wet, come on home."

But he goes anyway, and she sits in the car, looking at the rusty vessel and then at the men's faces. She tells the author: "I know them so well I could almost make drawings of them."

The Poet left Girard Point about 1:20 a.m. and was piloted into the Schuylkill. It was 9 a.m. when the ship pushed past landfall, and its radio officer messaged its whereabouts to the Coast Guard.

Just before midnight, the ship was 250 miles off shore when a third mate called home - the last contact from the Poet. He said nothing to his wife about the near-hurricane-force winds and roaring waves the Poet was heading into.

The ship wouldn't be reported overdue until Nov. 3, and five more days would pass before the Coast Guard began a search that covered more than 296,000 square miles and lasted 10 days.

No evidence of the Poet or its 34 men were found - not a life vest, nor a splinter of wood, nor a drop of oil.

The official explanation was that the Poet sank at sea in a violent storm that so overwhelmed the 36-year-old vessel that no one had time to put out a distress call.

"The sheer mystery of something just sailing out and never, ever appearing again - it's a blank screen, and you can project an awful lot of things on that," said Robert Frump, who cowrote an award-winning series in 1983 about the shoddy state of merchant marine ships for The Inquirer.

So into the void came the conspiracy theories. The Camden Courier-Post reported authorities were following a tip that drug smugglers tied to the New Jersey mob had hijacked the ship and intended to trade the corn to Iranians for heroin.

A more popular theory emerged, that the Poet secretly carried weapons in its fourth hold, and was diverted to Iran as part of the "October Surprise," an effort by backers of then-candidate Ronald Reagan to delay releasing American hostages until after the presidential election.

That's Zukier-Fredette's bet. Too many factors have led Hansy's mother to doubt the conclusion that the ship couldn't withstand the storm - the delay in reporting it missing or beginning a search, the Coast Guard's initial faulty math, which concluded the vessel was rolled by a wave.

"A ship doesn't just disappear," she said. "Something had to happen. They were doing something they weren't supposed to be doing."

Nicole Adelman has read all the theories. They might be true, they might not be, she says. She doesn't care.

"All they do is make me crazy," said the 37-year-old social worker from Erie.

She was 7 years old the day her father, Anthony "Jim" Bourbonnais, died on the Poet. He was 34, a third assistant engineer, from Newark, Del., making his last voyage.

"What I want to know," she says, "is who was my dad? I want to honor his memory."

She has carried a folder about the ship's fate with her since she went off to college. Every Oct. 24 she'd pull the binder out, look at the official reports and newspaper articles, and cry.

"That didn't tell me who he was, just how he may have died."

Five years ago her son, then a toddler, was banging on her dad's old diving helmet, which she displayed in her living room. She asked what the boy was doing. He said he was fixing it.

"I realized then I needed to know who the man was," she said. "I have three little boys now, all they know about their pepere is 'He's in heaven.' "

She began searching for people who knew her father, collecting stories about the man who made sure to send his younger sister a dozen roses on her birthday so everyone at her school would know it was her Sweet Sixteenth.

Adelman says she doesn't know what she'll do on the 24th this year. It will be something quiet and fun with her husband and kids, she said. Something to celebrate a life, not mourn a death.