Phila. police arrest suspect in 2007 murder case

Almost four years later, Antonio Quintin Clarke's murder had grown cold. Police discovered the 15-year-old's beaten and stabbed body wrapped in plastic behind the loading dock of a Grays Ferry electrical warehouse on the morning of Nov. 26, 2007. He was naked, except for a T-shirt pulled over his shoulders.

Almost four years later, Antonio Quintin Clarke's murder had grown cold.

Police discovered the 15-year-old's beaten and stabbed body wrapped in plastic behind the loading dock of a Grays Ferry electrical warehouse on the morning of Nov. 26, 2007. He was naked, except for a T-shirt pulled over his shoulders.

The Bartram High School special-education student had never been in trouble with police. He had an after-school job at a community center near his Southwest Philadelphia home and helped his single working mother take care of his physically disabled sister.

Detectives collected a carton load of interviews, but the neighborhood wasn't saying much, and there were few leads and no suspects.

Friday, cold-case investigators, armed with newfound DNA evidence, charged 29-year-old Tramine Garvin in the killing.

The week before his death, Clarke had shied away from a hallway fistfight at school, police said. He had been laughing at a joke, and another student thought he was laughing at him. Backing down, police said, made him a target for abuse in the neighborhood.

Scared, Clarke skipped classes for a few days, returning to his bedroom basement after his mother went to work.

When Garvin, who police say was trying to enlist Clarke and some of his friends into the Bloods gang, found out Clarke had not fought the other student, he decided to make him an example, police said.

At their first chance, Garvin and two unidentified young men, who Clarke thought were his friends, lured him to a neighborhood backyard they had covered in plastic and shower curtains, police said. Clarke, according to police, thought he was going to play video games.

Once they had him cornered, the group bound and beat Clarke and stabbed him repeatedly.

Garvin stabbed Clarke in the neck, killing him, police said. After disposing of the body, police said, the group returned and played video games.

"They thought he had made them look bad, and they killed him for it," said Lt. Mark Deegan of the homicide Special Investigations Unit.

The case unsettled even hardened veterans such as Deegan and Detective Bill Kelhower, lead investigator in the case.

"This was a young kid who was trying to do right, whose mother was trying to do right for him," Deegan said. "But the negative forces in the neighborhood - he couldn't get away from them."

The cold-case unit began working the investigation last November, Deegan said. The unit inherits cases from frontline detectives who are swamped with fresh homicides.

Investigators combed through stacks of interviews and case files to no avail, so they returned to the physical evidence recovered with Clarke's body.

Along with the plastic wrapping, a bloodied garden glove had been recovered, Deegan said. The hope was that updated DNA identification methods, unavailable in 2007, could find a suspect match.

Kelhower sent the glove to Ryan Gallagher, a technician at the Police Department's criminalistics lab, this month, Deegan said. Last week, a match came back for Garvin, who is incarcerated at Laurel Highlands state prison on gun and drug charges, records show.

When Garvin was brought to the homicide unit for questioning, detectives noticed a long scar on the inside of his hand. He said he had hurt it around the time of the killing on a broken window. Detectives now believe it happened during the attack.

He said he was a "mentor" to Clarke.

"He told an elaborate tale, which quickly unraveled," said one investigator.

Police are still seeking other suspects, Deegan said.

"We don't give up on cases," said Capt. James Clark, commander of the homicide unit.

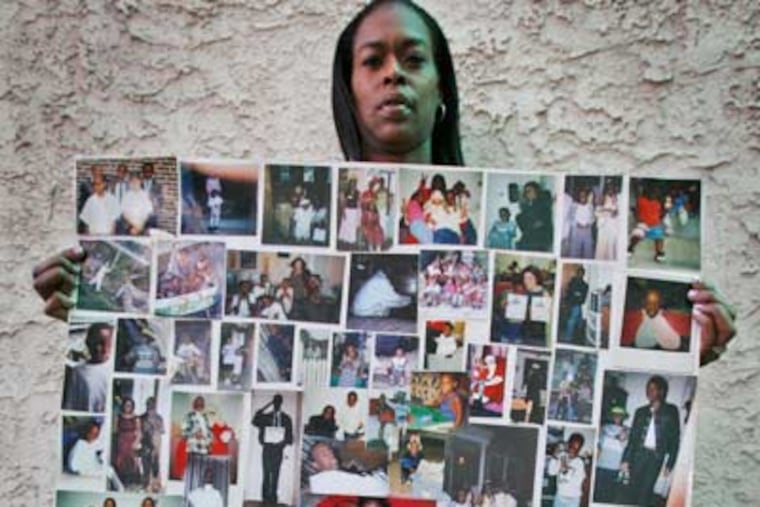

Thursday, Marie Clarke got word that the suspected killer of her son had been caught.

She has since moved her family from the Southwest neighborhood that took her youngest child, whom she called "Q." Living there was too painful, she said, because she suspected some in the community knew who killed Q.

Friday afternoon, she called in late to her school custodian job, and, carrying her son's funeral pamphlet, took the trolley to Bonaffon Street, where they had lived. She wanted her neighbors to know about the arrest.

She walked the street, and then she went to work.