Palestinians' old guard reflects ruefully

Aging militants lamented opportunities lost. "Maybe, just maybe, we should have shown some flexibility," one said.

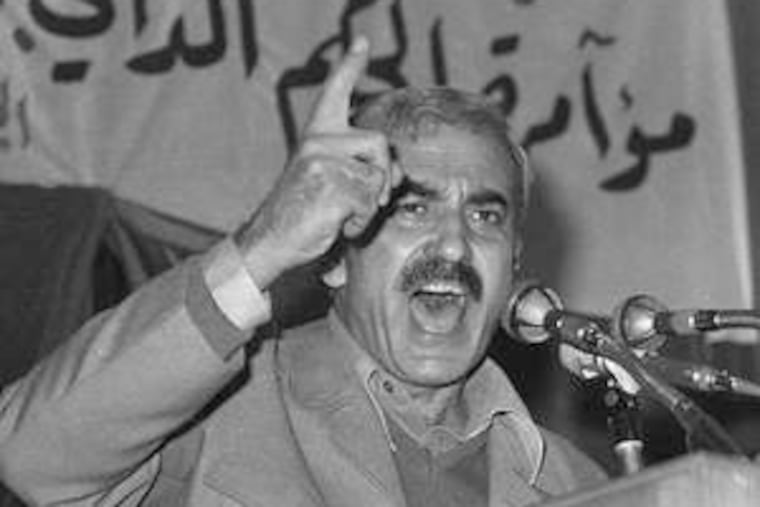

DAMASCUS, Syria - Looking back to the U.N. partition plan of 1947, which envisaged Jewish and Palestinian states living side by side in peace, Nayef Hawatmeh comes to the painful acknowledgment of an opportunity missed.

"After 60 years, we are struggling for what we could have had in 1947," laments the leader of the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine. "We have missed many historic opportunities."

In a year when Israel is celebrating its 60th birthday, Hawatmeh and his generation of leaders are still in exile and fading from the scene.

Speaking from their exile in Damascus, the Syrian capital, these graying revolutionaries radiate nostalgia and bitterness. They speak of wasted opportunities.

They voice anger at Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas for negotiating with Israel, but also at Hamas for taking their struggle down the path of radical Islam.

Hawatmeh and others of his generation - Ahmed Jibril; George Habash; the shadowy Black September movement; hijacker Leila Khaled - exploded onto the world stage in the 1960s and 1970s with deadly raids into Israel, the attack on the 1972 Munich Olympics, and a string of airline hijackings and assaults on passenger lines at foreign airports.

Branded as terrorists in Israel and the West, they saw themselves more in the Che Guevara mold, inspired by Cuba, Algeria, and the Viet Cong. They say their goal, steeped in Marxist and Arab nationalist ideology, was to liberate Palestine from an "imperialist" Israel.

"The whole world now says the Palestinians must have their state," says Ahmed Jibril, whose part of the alphabet soup of factions is the PFLP-General Command. He rejects any suggestion that his years of struggle came to nothing. "I am sure that if I don't see it in my lifetime, my son will. If not, then my grandchildren will."

But today the face of the Palestinian struggle is the suicide bomber, acting in the name of Islam, not nationalism.

The borders envisaged in the U.N. plan have been thoroughly scrambled. The war that followed the Arab rejection of partition left Israel ruling more land, and the territory left to the Palestinians is split - in conditions close to civil war - between the West Bank, where Abbas is headquartered, and the Gaza Strip under Hamas.

Some of the old-timers have paid a personal price. Jibril, 70, lost one of his sons, 38-year-old Jihad, in a car-bombing in Lebanon in 2002.

Time is thinning their ranks. George Habash, whose Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine specialized in hijackings, died in Damascus in January at 81.

While the leaders interviewed say they have no regrets, some of them wonder aloud whether things might have been different.

"Would you believe me if I tell you that if I had to do it all over, I would?" said Mohammed Oudeh, architect of Black September's 1972 Olympics attack that left 11 Israeli athletes dead.

"But maybe, just maybe, we should have shown some flexibility. Back in our days, it was, 'The whole of Palestine or nothing,' but we should have accepted a Palestinian state next to Israel."

They dislike Hamas' ideology.

"Muslim extremism can fascinate people for some time, but it will lead to nothing," said Oudeh, 71. "Resorting to religion is born out of the frustration that comes after a series of defeats."

As for Abbas, "I am disgusted every time I see him hug and kiss Ehud Olmert," the Israeli prime minister.

Khaled, the Palestinians' best known female hijacker, said the Palestinian leadership had "committed a lot of blunders, which delayed Palestinian statehood."

They jumped too quickly into negotiations with Israel and thus "defused" the Palestinian uprising and "blocked the golden path that I and other comrades paved for the Palestinians," she said in Amman, in neighboring Jordan.

But Hamas is not an option, she said, denouncing its takeover of the Gaza Strip last year as an "act of treason that divided the land and people."

Moussa Abu Marzouk, the deputy head of Hamas, countered that the old guard's methods were autocratic and produced repeated failures.

Among Israelis, too, there is recognition that the Palestinian leadership they cold-shouldered in the 1970s has been supplanted by a tougher foe, Islamic militancy.

"Of course it's better to deal with secular nationalists than religious extremists," said Yossi Melman, a veteran Israeli intelligence analyst.

"It was better back then, because along with the violence there was hope for talks, and negotiations did happen and agreements were made," he said. "But with Hamas, there is nobody to talk to. After Hamas, Israel will face al-Qaeda."