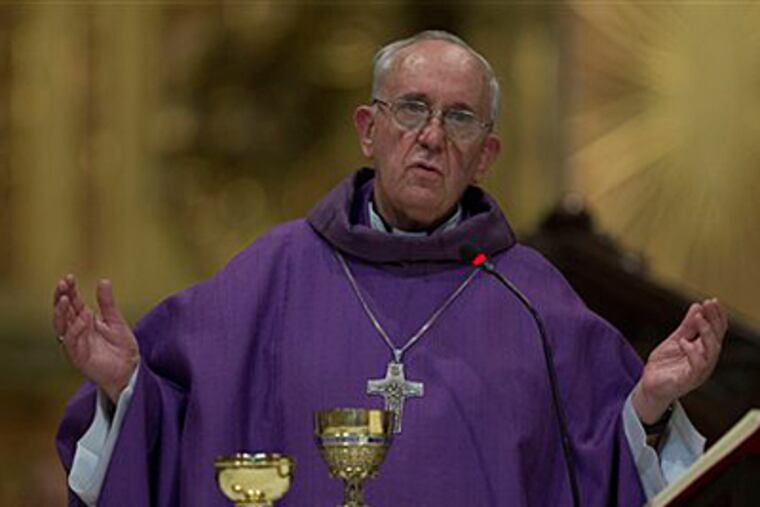

New pope: humble, soft-spoken, traditional

For all of the newness, Francis is also very much from the old school.

VATICAN CITY - The man who will move into the 10-room papal residence inside the vaulted gates of the Holy See lives in a simple, austere apartment across from the Cathedral of Buenos Aires. In a city with a taste for luxury and status, he frequently prepares his own meals and abandoned the limousine of his high office to hop on el micro - Argentine slang for the bus.

A staunch conservative and devout Jesuit in Latin America's most socially progressive nation, Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, now Pope Francis, is the product of an almost Solomon-esque choice by the princes of the church.

The 76-year-old hails from a country and a continent where the once powerful voice of the church is increasingly falling flat, losing ground - as it is in Europe - to a tide of more permissive and pragmatic faiths and to fast-rising secularism. He gives voice to a church whose center of global gravity is shifting south.

But the first Latin American pope also represents a cultural bridge between two worlds - the son of Italian immigrants in a country regarded by some as the New World colony Italy never had. For many Italians, his heritage makes him the next best thing to the return of an Italian pope.

Francis is a fierce critic of socially progressive trends including gay marriage, representing a continuity of Benedict XVI's conservative doctrine. Though questioned for some of his actions during Argentina's "dirty war," he may also be a target hard for progressives to hit. In recent decades, he has emerged as a champion of social justice and the poor who spoke out against the evils of globalization and has slammed the "demonic effects of the imperialism of money."

At the same time, in the age of 24-hour news cycles and the cult of celebrity, he is described by some as so retro as to be something oddly new. He represents a flashback to an old-school view of the Catholic leaders as humble, soft-spoken clerics who walked among their flock and led by example - albeit also one who has used the Internet as a tool to reach lapsed Catholics.

"He knows how to take a municipal bus. When he became a local ordinary of Buenos Aires, he moved from a large, impressive home to a modest dwelling. He has a sense of social justice, but he can be seen as quite conservative doctrinally," said the Rev. Robert Pelton, CSC, the director of Latin American Church Concerns at the University of Notre Dame.

"He's a simple person," Pelton said. "The fact is that he has a straightforwardness and simplicity that is quite unusual in public figures of our time."

It remains unclear whether even Latin Americans will respond with newfound energy to Bergoglio's ascension to the throne of St. Peter. Among many of its neighbors, Argentina is seen as a nation apart - a country that fancies itself more European than Latin American, with many likely to see the rise of an Italian Argentine as largely unrepresentative of the region as a whole.

"Argentina is so secular today, a more eurocentric Latin country," said Joseph Palacios, specialist in religion and society in Latin American at Georgetown University. "Geopolitically it makes sense in terms of bridging Europe to Latin America or the third world, but Argentines don't see themselves as being third world."

In his global introduction from the balcony of St. Peter's, he addressed the crowd in Italian, one of three languages he fluently speaks. He presented himself as plainspoken, humble, even quaint - directing his comments seemingly to the citizens of his new city, Rome, more than to the 1.2 billion Catholics worldwide.

Born in Buenos Aires on Dec. 17, 1936, Bergoglio was raised in a struggling middle-class home of a railroad worker and homemaker. Ordained a priest in 1969, his ascent toward higher office occurred during a time when the Catholic Church in Argentina stood accused of at best failing to speak out, and at worst being complicit, in the harsh right-wing dictatorships of the "dirty war" that saw the disappearance of an estimated 30,000 dissidents between 1976 and 1983.

A book by the noted Argentine journalist Horacio Verbitsky, The Silence, contends that Bergoglio, then a Jesuit leader, lifted church protection from two leftist priests of his order, effectively allowing them to be jailed for refusing to end their politically charged ministry in Buenos Aires slums. Yet Bergoglio's supporters have cited a lack of evidence, countering that he endeavored to aid dissidents in danger during a dark period in Argentine history.

"History condemns him," Fortunato Mallimaci, the former dean of social sciences at the Universidad de Buenos Aires once said, according to Reuters. "It shows him to be opposed to all innovation in the church and above all, during the dictatorship, it shows he was very cozy with the military."

One thing is certain: He rose fast. In 1992, John Paul II named him assistant bishop in Buenos Aires, then made him archbishop five years later. He served on a number of Vatican commissions and in 2005 is widely believed to have come in second to Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger - now the pope emeritus - to succeed John Paul.

But Bergoglio was mostly absent from the short lists for pope this time around and has been largely seen as a Vatican outsider. That is seen as positive by reformers.

In recent years, he became known for creating new parishes, reorganizing administrative offices, and spearheading a fiercely conservative social agenda. He has butted heads repeatedly with increasingly secular Argentine governments. In 2006, he attacked a proposal to legalize abortion under certain circumstances by accusing the government of lacking respect for human life.

In 2010, he rallied against a measure that saw Argentina become the first Latin American country to legalize same-sex marriage. He also argued that a decision by the government to allow same-sex couples to adopt would deprive children of "the human growth that God wanted them to have by a father and a mother."

In a 2012 interview with the Italian newspaper La Stampa, Bergoglio spoke of his desire to broaden the church's reach and increase its involvement in the world, and he alluded to the infighting that plagued the Vatican during the tenure of Pope Benedict XVI.

"We need to avoid the spiritual sickness of a church that is wrapped up in its own world," Bergoglio told the Italian newspaper. "If the Church stays wrapped up in itself, it will age."