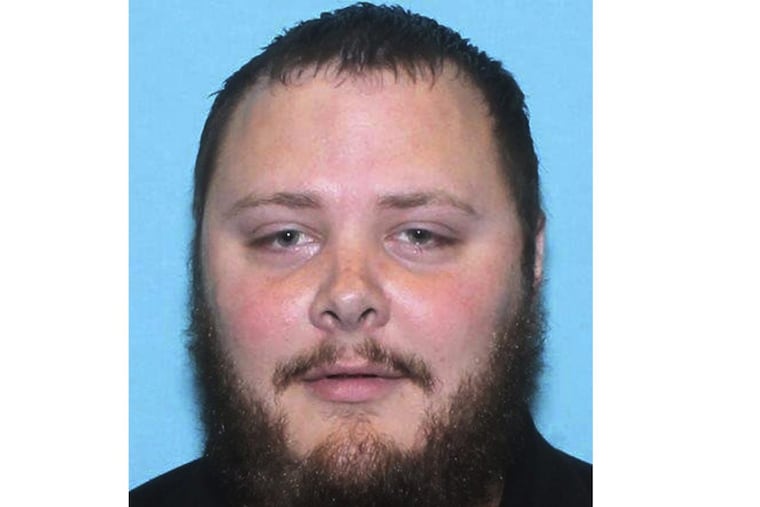

How the church shooter slipped past the Air Force and FBI

Kelley, who served at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico, should have been barred from buying firearms and body armor after he was convicted on domestic abuse charges.

The Air Force is facing scrutiny after it was revealed this week that it failed to follow policies for alerting federal law enforcement about Devin Kelley's violent past, therefore allowing him to obtain firearms before the shooting rampage that killed at least 26 churchgoers Sunday in Sutherland Springs, Texas.

Kelley, who served at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico, should have been barred from buying firearms and body armor after he was convicted on domestic-abuse charges.

Here's what you need to know:

What happened to Kelley?

He was sentenced to a year in prison and kicked out of the military with a bad-conduct discharge following two counts of domestic abuse against his wife and a child. In a statement, the Air Force said that Kelley's domestic violence offense was not entered into the National Criminal Information Center database, which is used by gun-sellers to screen for felons and violent criminals who are prohibited from buying firearms.

How was Kelley able to purchase weapons?

Kelley was able to purchase two weapons from a firearms retailer after passing federal background checks this year and last. It is unclear whether he used the same weapons in Sunday's shooting.

But his ability to buy guns highlights the Air Force's failure to follow the Pentagon's guidelines for ensuring that violent offenses are reported to the FBI. Domestic abuse convictions are among the crimes the military services are required to report.

What was the military's response?

Lawmakers called on Defense Secretary Jim Mattis to determine how many former service members who have been convicted of violent crimes also have been improperly documented. Mattis said Tuesday that he had directed the Pentagon's inspector general to investigate further.

"If the problem is that we didn't put something out, we'll correct that," Mattis said.

Air Force Secretary Heather Wilson said Thursday she expected that a draft report due next week would detail how the service failed to send Kelley's information to FBI criminal databases. Additionally, Air Force databases are being searched for other instances of violent offenders who might have fallen through the cracks, Wilson added.

Did Kelley receive a proper punishment?

Kelley's case shows the military "has an archaic, ineffective sentencing system they have refused to reform," said Don Christensen, a former Air Force chief prosecutor. In Kelley's case, a jury of airmen – not a judge – chose his sentence.

Jurors typically hand down lighter penalties, Christensen said, and Kelley's crimes probably should have demanded more severe punishment. Had Kelley received a dishonorable discharge, his information almost certainly would have reached the FBI criminal database.

"Sentences typically skew light in crimes of violence than what you see in civilian world," Christensen said, calling the appointment of a jury in a case of such magnitude both highly unusual and "disturbing." Severe child abuse carries a maximum prison sentence of five years in the military court system, which can be similar to offenses like one-time drug use, he said.