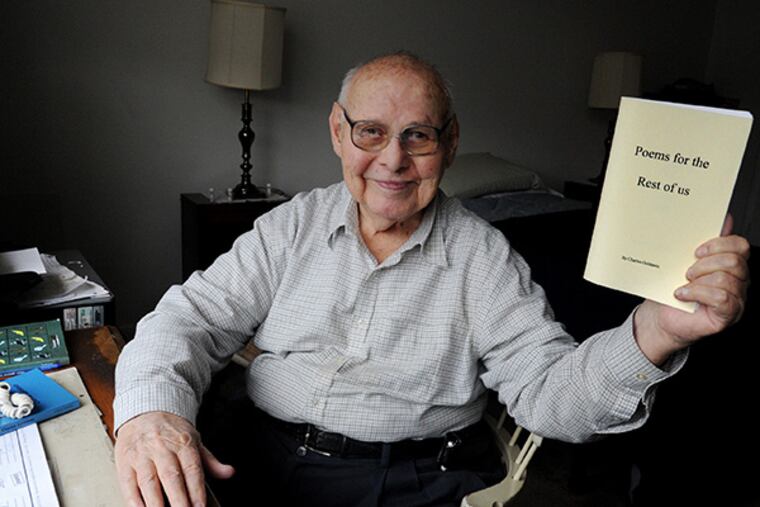

Cherry Hill man expresses life in poetry

For more than seven decades, Charles Goldstein has rarely put down his pen. He wrote his first poem in eighth grade. During World War II, he faithfully sent letters to his sweetheart, but when he wouldn't marry her, "she burned them all."

For more than seven decades, Charles Goldstein has rarely put down his pen.

He wrote his first poem in eighth grade. During World War II, he faithfully sent letters to his sweetheart, but when he wouldn't marry her, "she burned them all."

After the war, Goldstein began composing poetry "without knowing what a poet was." Later, he authored Turning Corners, a novel inspired by lonely housewives he encountered as a Willingboro electrical contractor.

"But the whole time I was a contractor, I was a poet," says Goldstein, seated at the dining-area table of his Cherry Hill apartment.

"Let me show you something I started writing today," he says. "It's about a great horned owl. My grandson sent me a picture of it."

Goldstein, who turns 91 next Thursday, returns to the room with a sheaf of loose-leaf paper on a clipboard. He writes in longhand and converts the finished work to typescript on the computer in his bedroom.

Largely self-taught, he has collected hard copies of his 3,000 poems in a half-dozen binders lining a shelf adjacent to his desk. An additional 2,000 poems await completion.

Like the hanging plants you water, / you spend your life inside a room / waiting, walking through your mind.

"I never throw anything out," says Goldstein, whose work has appeared in 16 self-published volumes, as well as in local poetry publications and college literary reviews.

And while he doesn't care for what he calls "academia poetry," Goldstein is proud that a 2007 edition of the respected Mad Poets Society anthology includes his Submarine Alert, 1943.

The poem begins:

Three days into the Atlantic / three decks deep, /

deep in the bowels / of a camouflaged ship, / I slept.

A thin metal skin / parting my bunk from the sea. /

"The first poem I ever wrote," he recalls, "was about a conversation between a table, a lamp, and a chair every time the trolley went by."

This was in South Philly, where his parents ran a grocery near Sixth and Jackson and some kids called him "Scarface"; at 3, he had been thrown through the windshield of a 1927 Ford.

But it was not until a blind date with a woman who worked for a speech therapist did he realize that the accident had so damaged ("frozen") his larynx that some people couldn't understand his words.

Is that why he's labored for so long to express himself on the page?

"No," insists Goldstein. "I just wrote. . . . But then I took a night class, and I realized, 'I'm a writer, and a poet.' "

He's sold a few books ("I probably made $3,000 in 50 years") but also has endured criticism. Once, a professor at a highbrow poetry gathering in Doylestown dismissed his work as "trash."

"I was embarrassed," says Goldstein.

Long involved in poetry appreciation groups in South Jersey, he's even communed with the ghost of Walt Whitman at the poet's former home in Camden.

The silence suddenly disappeared / as a warmth pervaded the atmosphere.

And while Goldstein has had his differences with some local poets, others hold him in high esteem.

"He's got the heart of a poet," says Camden's Rocky Wilson. "I'm so happy he's still plugging away."

Goldstein admits he's slowing down a bit. His wife, Ruth, died two years ago, and he no longer drives at night, so it's difficult to get to readings and other poetry events.

But solitude can be an inspiration.

"I sit here, and I'm doing nothing, then all of a sudden, I'm writing," he says.

"The other day I started writing a poem about how great it would be to sit with Robert Frost as he wrote The Road Not Taken."

One of my all-time favorite poems, I say. So, are you going to keep on writing?

"Of course," says Goldstein. "I'm going to write until I die."

I'll take his word for it.