During his 54-year career, Bill Fritz and the men and women he trained won enough championships, titles, and honors to fill a trophy room. Or a hall of fame.

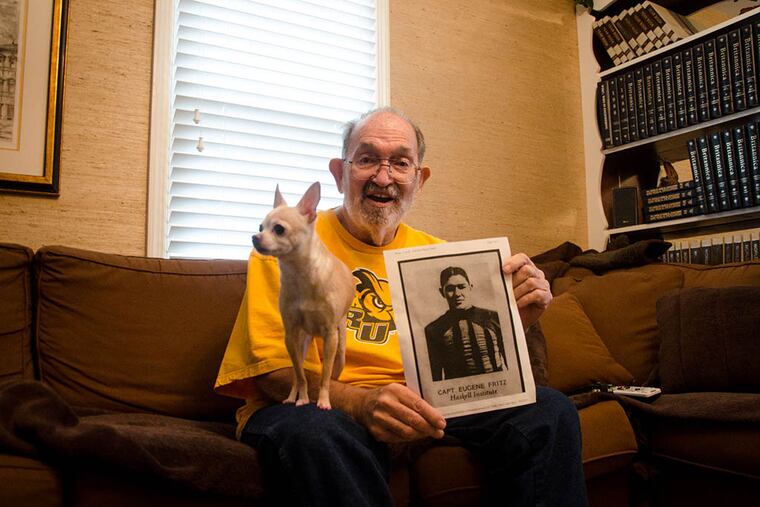

But what the beloved cross country and track and field coach most wants to show me is a black-and-white photo of his father, Eugene.

"I can't say enough about him," says Fritz, 76, who retired from Rowan University in 2014 after coaching 69 NCAA Division 3 national champions, 277 All-Americans, and 44 NJAC champions. He also trained four-time NCAA champion javelin-thrower Mike Juskus.

"My father was a Cherokee, born in Indian Territory in 1908," Fritz tells me, crossing the TV room at the Moorestown home he shares with his wife, Enger. He hands the photo of his formidable-looking dad as a young man; he keeps it on the refrigerator "for inspiration."

A grandfather of seven, Fritz is battling prostate cancer and moves with difficulty. He was diagnosed right when he retired.

"I expected to be busy after I retired, but I spend all my time on the couch," often accompanied by his Chihuahua, Holly. He hasn't been able to take one of his regular hour-long outdoor walks since last August.

"My father coached football and track, and he started taking me to practice at age two," he continues. "He worked at the Cheyenne Agency, which was a reservation, and he gathered up the runaways, because he had been a runaway.

"He was an easygoing coach. But he was hard as a rock if you did something wrong."

It was in Pierre, S.D., that Fritz began running cross country at the high school in the early 1950s. "I loved it right away," he says.

His mother, Ethel, would drive him in the family's black Chevy sedan five miles outside Pierre to the most distant of his dozen newspaper delivery customers.

He'd run and deliver the five miles back home. "Sometimes I'd get in snow up to my crotch," he recalls.

Fritz attended Northern State College and South Dakota State University, where he earned a master's degree in exercise physiology, and began his college-level coaching career. He arrived at Rowan, then Glassboro State College, as men's cross country coach in 1971.

Although the facilities were "nonexistent," at least the roads through the peach and apple orchards around Glassboro were paved, and the distances between the locations of meets were shorter than in the Midwest.

He remembered how his father worked with troubled boys, "teaching them discipline" through running. "They weren't bad kids," he says. "They were just lost. He helped them find themselves."

At Glassboro, the kids weren't lost, but the running program wasn't getting anywhere until Fritz and his colleague (and former Olympian) Oscar Moore, who started the men's track and field program, helped build the school into a powerhouse.

"In 1978 I was at Montclair High School, and Bill Fritz called me to talk about Glassboro State. I had no idea there was such a school," Derick "Ringo" Adamson says.

"He was the first good one I ever recruited," laughs Fritz, who convinced Adamson to run for Glassboro.

And after Adamson graduated, the coach helped him qualify for the marathon for his native Jamaica in the 1984 Summer Olympics. Adamson is now coach of the women's cross country and track and field program at Rowan.

"I learned so much from Fritzy, about dealing with different kids, and I'm using the same technique and getting results," Adamson says. "He never screams. He just explains stuff to you.

"He was tough, but a good tough," says Adamson, who is organizing a "Cross Country Open" in Fritz's honor on Sept. 19 at Rowan College at Gloucester County in Sewell, N.J. "He was the father I never had."

Fritz remembers one young man from North Dakota whom his father coached, named William Lone Bear. Fritz doesn't remember which tribe he belonged to, but he does recall that with guidance, William became a "wonderful" runner.

"I miss coaching," he says. "At 3:30 every day, I'd be doing something positive. I'd be spotting a kid who needed help, and helping him out.

"I thought of it as carrying on my father's work."

Eugene would be proud. Ethel would be, too.